Back • Return Home

THE MOTIVATION COMPLEX: LINKING NEEDS, DECISION MAKING,

COMMUNICATION, RESOURCES, POWER, AND INFLUENCE

Lane Tracy

Ohio University, Copeland Hall, Athens, OH 45701, USA

ABSTRACT

The topics of motivation, decision-making, communication, needs, resources, power, and influence are often considered quite separately in research and teaching. A study of human motivation, for instance, may involve all of these elements, yet the focus in such studies tends to narrow toward the link between thought and action. There are complex models for each of the separate elements, and all of these models interact. A more complete picture of motivation might be obtained by considering the complex of interactions among these elements. This paper will attempt to model the motivation complex and suggest routes for further research.

Keywords: motivation, needs, decider, communication, power, living system

INTRODUCTION

Motivation has always been a topic of great human interest. All forms of life seem to violate the physical principle that an object at rest tends to remain at rest until subjected to external force. We therefore ascribe motives to living systems in order to explain their autonomic behavior. These motives have become a subject of interest to scholars in such diverse fields as psychology, political science, business, ethics, religion, and the law.

Motivation is defined in this paper as the process that determines the direction, intensity, and persistence of a living system's behavior (Mitchell 1982). Direction refers to the nature of the behavior and implies that it is goal oriented. Intensity of motivation is usually interpreted as the degree or amount of effort devoted to the behavior, and persistence refers to the duration of the behavior. Living systems are those concrete, protoplasm-based entities that exhibit the basic characteristics of cellular life (Miller 1978).

The term "motivation" is usually applied to human (or at least animal) behavior. Yet the process as defined occurs in all living systems. In addition to the cellular level itself Miller (1978) identified six other hierarchical levels of living systems: organ, organism, group, organization, society, and supranational systems. An eighth level, the community, was later interpolated between organizations and societies (Miller & Miller 1990). Motivated behavior is exhibited at all of these eight levels.

Motivation is a complex process involving, ultimately, all of the twenty critical subsystems of a living system (Miller 1978; Miller & Miller 1990). Each critical subsystem engages in motivated processes for its own sake and for the sake of the system as a whole. The decider subsystem gathers information from the other subsystems and issues instructions that are intended to elicit coordinated behavior from the subsystems. Subsystems may also interact directly, thereby motivating each other, as when the producer draws materials from storage and stores finished products.

Interactions between living systems are likewise motivated. That is, overt acts of one system motivate responses from other systems and vice versa ad infinitum (Tracy 1989). Such interactions may occur among living systems at the same level or between two or more levels.

Elements that may enter into the motivation process include purposes, goals, drives, needs, desires, choice or decision making, ability, communication, outcomes, feedback, perception, resources, rewards, power and influence. Each of these elements has been studied in its own right. Thus, a model of motivation that attempts to account for each of these elements and the interactions among or across several levels of living systems must be a complex model.

ELEMENTS OF THE MOTIVATION COMPLEX

In building a complex model one must start somewhere. Let us begin by recognizing certain important characteristics of living systems. This will lead us to examination of each of the elements listed above.

Motivation from within a Living System

Every living system is an open system. According to Miller (1978, 18) living systems "maintain a steady state of negentropy even though entropic changes occur in them as they do everywhere else." Such systems require inputs of resources, which are matter/energy or information used by a system to maintain itself, actualize its potential, and propagate its essence (Tracy 1994). A living system also requires outputs of wastes, products, and excess resources.

Resources

Resources are consumed by living systems. As resources are used or dissipated, they must be replaced. In order to replace resources the system must have power with respect to its environment. Some resources (e.g., air, water, some foods, sounds, sometimes heat and light) are abundant and require only that the system have the ability to import and process them. Other resources (e.g. coal or oil, cultivated or husbanded food sources, scientific information, artificial heat) require work on the part of the system to extract or develop the resource.

When a system possesses or controls scarce resources that are not immediately required by the system, those resources provide the system with power (Tracy 1994). Virtually every living system has some power. For instance, poor people may have excess muscular energy and skills; infants can satisfy maternal longings and also hold the future of their parents' genes. Such excess resources may be traded with any other system that values them positively, or used as a threat against any system that wants to avoid them (e.g., avoiding a baby's cry by anticipating and meeting the baby's needs).

Systems communicate in order to obtain resources from each other. They must communicate about what excess resources they hold, their willingness to use or part with those resources, what resources they desire in return from other systems, and the perceived worth of the resources to be traded.

Some resources may best (or only) be obtained by means of cooperative endeavor with other living systems. Such cooperation may be preprogrammed or it may result from negotiation. In the latter case communication between systems may center on such issues as what resources each system will contribute and the relative worth of their contributions to the enterprise.

Needs

Resources fulfill requirements of the system. These requirements are often termed needs. Needs are influenced by values (innate and learned) of the system. These values may come originally from the template of the system but may also be learned or modified by learning.

Values specify not only what resources are required by the system but also the preferred level of each resource under various conditions. These conditions include the rate of consumption and criticality of the resource, availability and cost of replacements or substitutes, knowledge of availability, and competing demands for other resources.

Needs vary constantly in intensity as resources are consumed or imported, values change, substitutions are made, and other needs are aroused or fulfilled. A living system also must export or eliminate wastes, products, and excess resources. The needs related to elimination or export have much the same effect on decision making as do the needs for resources. That is, both a lack of resources and an oversupply of them influence the choice of action to correct these conditions.

Some needs appear to directly stimulate preprogrammed responses. Such needs are often termed drives (Murray 1938). In higher-level systems, however, most responses must be chosen.

Decision processes

Decision making is the part of the motivation process in which messages about needs are assessed and choices of behavior are made and communicated. In decision making, needs influence valences of expected outcomes, which in turn influence the choice of acts to obtain those outcomes. Decisions are also influenced by:

• expectancies (i.e., probability estimates) that given behavior will achieve expected outcomes and that immediate outcomes will lead to further outcomes;

• goals (i.e., values related to external outcomes);

• moral or ethical values;

• competing needs and demands, including the needs and demands that determined the choice of current behavior;

• timing and sequencing of behavior and of awareness of needs; and

• feedback from the outcomes of current behavior.

Decisions must be made about the direction, intensity, and persistence of the behavior of the entire living system and of its components. Decisions influence behavior (both the how and how much), which in turn influences outcomes. Outcomes influence needs and expectancies through feedback. Outcomes also influence the accumulation or loss of power in the form of excess resources.

Ability

Motivation is also influenced by the ability of the system to carry out decisions effectively. Estimates of ability are part of the equation used in choosing acts. These estimates are influenced by training, advice, and feedback from outcomes.

At any given moment a living system is likely to have multiple needs for a variety of resources. An effective system may be able to pursue the fulfillment of several needs at once. Indeed, a well-chosen act may be one that is expected to fulfill several needs, and that may be one of the criteria used in choosing acts.

Feedback

As needs are fulfilled, outcomes are communicated back to the decision process, new needs arise, and new behaviors are chosen. Failure to attain expected outcomes is also fed back into the decision process. Failure may cause the system to reevaluate the likelihood of future success, which may in turn lead to greater effort or a decision to try something else. It may be necessary to divert behavior away from other goals in a renewed effort to fulfill more critical needs. Long-term failure to fulfill needs may begin a downward spiral in which constant stress interferes with the system's ability to fulfill even the most urgent needs.

Motivational Interaction with Other Systems

The motivational elements that we have examined thus far lie primarily within a given system. Living systems are not closed, however, and a complete picture of motivation requires that we consider interactions with the environment. Interactions with other living systems are particularly important in the motivation complex.

Communication

Communication is the process that connects all of the other elements of motivation. Communication is required in motivational interactions between systems, where it is a key part of the process of influence. That is, communication is used to express power in order to obtain needed resources from other systems. Communication may be used to inform other systems about what is needed, what can be offered in exchange or threatened if the resources are not made available, willingness to exchange or expend resources, and compliance or defiance toward the wishes of the other system(s). The motivation of each system is linked to other systems through communication of intentions, desires, and perception of overt behaviors. Each system is thus influenced by the behaviors of all other systems within its field of perception.

Perception

No matter what the intended message may be, communication depends on perception. During the communication process all information is filtered in accordance with needs. Some information is ignored or blocked, other information is condensed, edited, misinterpreted, or expanded. The degree and direction of filtering greatly affects communication.

Decisions are made on the basis of a system’s perceptions of its own needs, goals, abilities, power, and the supportiveness of the environment. Acts involving interaction with other systems also involve perceptions of the needs, goals, abilities, and power of those systems.

Power

Whenever two or more living systems interact in their behavior, power is a key determinant of the outcomes. Power lies in the possession or control of resources, particularly when a system holds more than enough of a resource for its own needs. Assuming that such excess resources exist and that they have either positive or negative valence for another system, they may be offered in trade or used as a threat, thereby giving one system power over the other. In most situations, however, both or all parties have excess resources and no system’s power is absolute.

Power is influenced by:

• one's own needs and the willingness to forego gratification of those needs;

• the needs of other systems;

• one's ownership or control of resources;

• the cost of storing and maintaining resources, and

• the cost of expending them (Tracy 1997).

Influence

Power is converted into influence by means of communication. In order for its power to be effective, a system must communicate the source of its power, its willingness to use its

resources, what is wanted in return, and perhaps the consequences of failure to comply. The other system(s) must also correctly perceive these communications. Influence occurs when the other system(s) are motivated to respond to power.

MODELING THE MOTIVATION PROCESS

Each of the components of the motivation complex has been examined, tested, and modeled extensively. The connections between some components have also been noted, particularly the needs-behavior link. Yet the complex as a whole, with its multiple interactions, has rarely been examined. The purpose of this paper is to try to model the interactions among needs, decision making, behavior, communication, perception, resources, power, and influence, in order to obtain a more complete picture of motivation.

There are two starting points for modeling the motivation complex, one lying within the living system and the other in its environment. The first source is the values of the system. All living systems possess a set of values with respect to the requirements of the system. Some of these values are set by the template of the system. The initial template of a living system is imbedded in its genetic structure plus (in the case of a social system) its charter. The template may be modified by maturation and learning, however. Thus, many values are learned and are determined, at least in part, by the decider subsystem. Values, whether innate or learned, represent the system's knowledge of its requirements and preferences.

The second starting point is resources. Resources capable of fulfilling a system's requirements exist both within the system and in its environment. Living systems are able to store various amounts of resources for various lengths of time, and to maintain an inventory of these resources. Living systems also search their environment for resources to replace those that are consumed or dissipated by the system. The amount, availability, quality, and cost of these resources constitute data which the system must incorporate into its decision processes.

Component Models

Our model of the motivation complex will be built up from several component models. Let us begin with a model of values and resources, as indicated above.

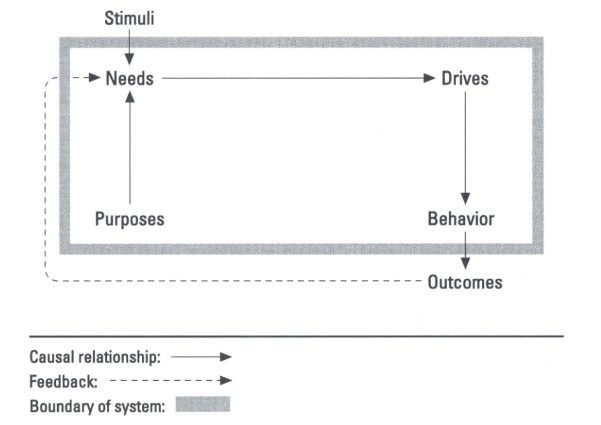

Model of Needs

System values and resource inventories come together in the model of needs shown in Figure 1 (Tracy 1986). In this model values define the ideal level of each resource within the system. Comparison of the ideal with the actual level determines the strength of need for that resource.

Figure 1. Model of the Need Assessment Process.

When the amount of a resource in the system exceeds the ideal level, strength of need is negative and represents a motive for extruding some of the resource from the system. Physicians are well aware, for instance, that you can have too much of a good thing and that, for example, the human body must sometimes reject overly large doses of vitamins and minerals.

As noted before, values are subject to change through learning. Thus, the ideal level of a resource may change over time. For instance, what is ideal for maintenance of the system may not be sufficient for actualization of potential (e.g., growth and development) or for propagation of some aspect of the system (e.g., sexual reproduction or establishing a colony).

The amount and quality of a resource in the system is also subject to change, often rapidly, as the resource decays or is consumed. Thus, needs tend to fluctuate and must continuously be reevaluated. Because of the natures of different resources and the ways that they are used by the system, some needs fluctuate rapidly or in regular cycles while others change slowly or irregularly. The human body's need for oxygen would be an example of a rapidly fluctuating cyclical need, whereas the need for information about the environment (e.g., weather, temperature, dangers) is likely to change slowly and irregularly.

Our model of needs is not closed. It is open to learning and to inputs of information about the environment and about changes in the levels of resources in the system. In turn it influences the decision-making process, as shown in Figure 2 (Tracy 1994).

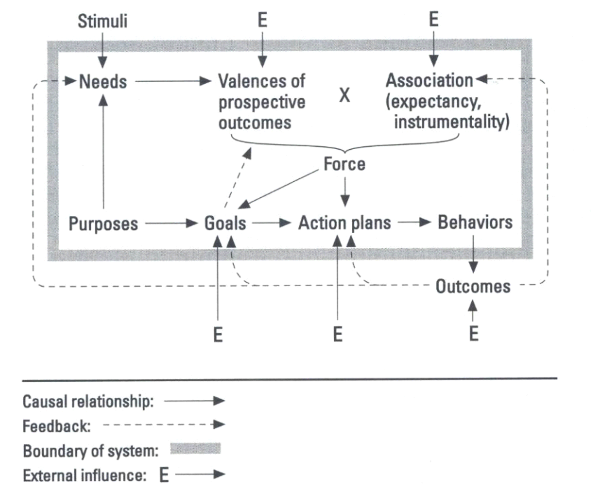

Choice of Behavior

Figure 2 presents two models of the process by which acts are chosen and implemented. The model of template-directed motivation (Figure 2a) is based on drive theory (Murray 1938). The model of decider-directed motivation (Figure 2b) stems in part from Vroom's (1964) expectancy theory. These are the core models of the motivation complex.

Figure 2a. Model of Template-Directed Motivation.

Beginning from perception of needs, purposes, and goals, the models indicate that choice of behavior is directed either by drives programmed into the system’s template (Figure 2a), or else by calculations of the expected value of various potential acts, leading to the choice of the act having the greatest force behind it at the moment (Figure 2b). The process of directing behavior is ongoing. At any moment feedback from outcomes may lead to reevaluation of needs and activation of a new drive or to choice of new behavior. An internal change in awareness of needs may also bring a different drive into play or raise a different act to the highest level of force.

Multiple acts may be in play at the same time and may be competing for the resources of the system. In assessing potential acts the system must consider what acts are already under way and must judge whether any newly chosen act is likely to interfere with fulfillment of existing commitments. The costs of such potential interference must be incorporated into the calculations. Certain acts may be complementary; that is, one act may provide resources for another, or both may be directed at the same purpose or goal.

Figure 2b. Model of Decider-Directed Motivation.

Influence

There are several points at which choice of behavior is subject to external influence. We have previously noted that needs change in response to feedback about changing levels of resources. For instance, as a chosen act achieves the desired outcomes, a particular need may become temporarily fulfilled and may thus cease to be a motivator. (Another way of putting this is that the valence of the resource decreases.)

As an outcome leads to the attainment of a goal, feedback to the goal causes the valence of that outcome to decrease. If, on the other hand, outcomes do not match goals, the action plan may be reviewed. This is the classical control process. Feedback may also alter the expectancy that a given act will lead to a particular outcome.

Influence results from the application of power. In the examples above the power exists in the form of information and the application is from one component of the system to another. In general, "power lies in possession or control of excess resources and the dependency of other systems on those resources (Tracy, 1994, 76)." The decider subsystem is dependent on other subsystems and the environment for information. In Figure 2b the feedback information is filtered and processed by transducers and the channel and net subsystem. It is also controlled by whatever external systems may be involved in producing outcomes. External systems are also the sources of the external influence shown in the figure.

Texts and treatises on motivation often focus specifically on how one system, such as a manager, can use power to exert influence on the choices made by another system, such as an employee. Figure 2b shows the major points (designated by E→) at which influence may be applied. Besides information, the form of power used may be material (e.g. rewards of food, clothing) or energy (e.g., help with a project).

Communication

Application of power for the purpose of influence usually requires communication. At the minimum, unless template-directed choice is involved, it is necessary for Party A to communicate what is wanted from Party B. If rewards or punishments are contingent on B's choice, that must be communicated as well. There may well be a negotiation between A and B as to what will be exchanged and the willingness of each party to do so.

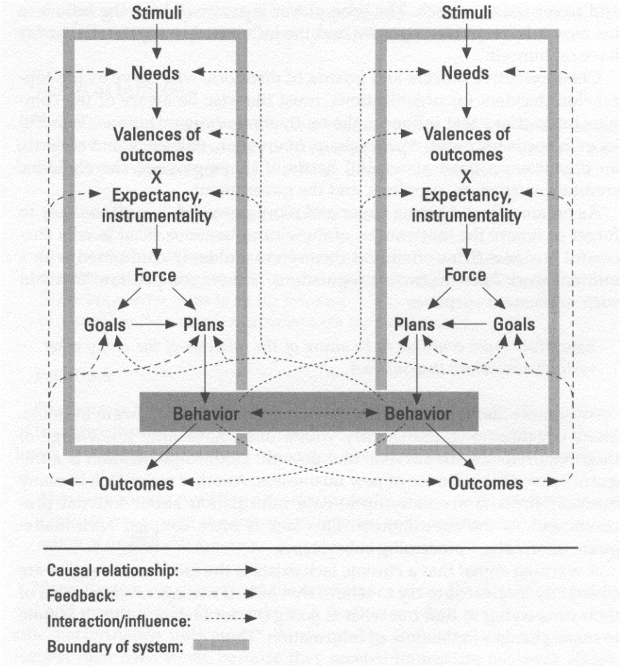

Figure 3 is a general model of the communication process between any two living systems. The systems may be at the same or different levels. Communication can be a one-way process, but is often two-way. Two-way communication aids the parties in understanding each other clearly.

Figure 3. Model of the Communication Process between Systems.

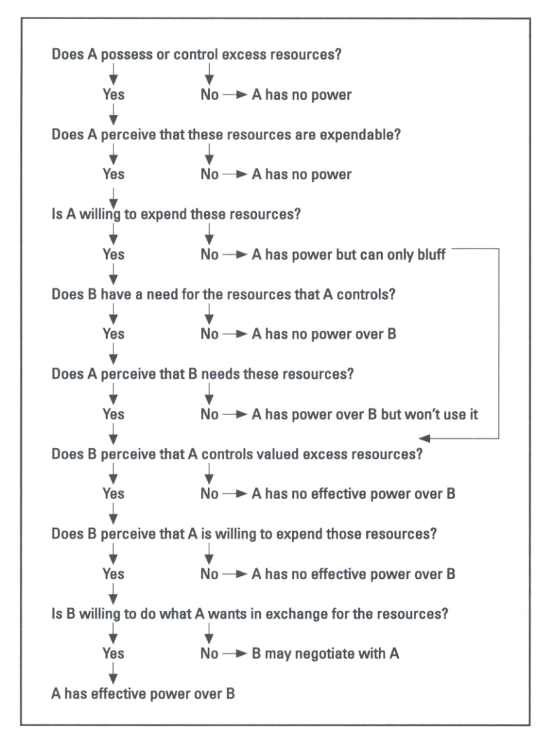

Applying this model of communication to the process of influence described above results in the flow chart shown in Figure 4. The chart shows that several steps of communication are normally necessary in order for one system to influence another.

Figure 4. Model of the Process of Converting Power into Influence.

Communication requires perception, a process whereby information is received, categorized, and recognized or interpreted. Some incoming information is filtered out at the boundary or input transducer; thus, it is not perceived at all. Miller assigns the perception process primarily to the decoder subsystem, with some help from the associator subsystem.

Although we may speak of intended communication - i.e., the information that the sender thinks is being communicated - only the information that is perceived has actually been communicated. Often this differs from the intended message because of distortions, elisions, expansions, and misinterpretations.

If one system intends to motivate another in a particular direction, one of the key tasks is to communicate clearly. This may involve anticipating misinterpretation and other perception problems, and designing the communication to overcome them. Multiple channels, repetition, and feedback are commonly used to try to overcome problems in communication. If also helps to understand the needs and limitations of the intended audience. A message is much more likely to be perceived if it meets a need of the listener and is couched in simple language.

Figure 5. Model of Motivational Interaction between Systems.

The motivation of one system by another is modeled in Figure 5. The model consists basically of two models of decider-based motivation linked by communications of influence. Note that the relationship is reciprocal. Any two systems in such a relationship tend to motivate each other.

Model of the Whole

The components of the motivation process are combined in the model shown in Figure 6. For the sake of simplification the many levels of living systems are collapsed into a single level and only some of their critical subsystems are shown. The model employs a set of symbols developed by Miller to represent the twenty critical subsystems and flows between them (Miller 1978). Two new symbols representing the template and values have been added.

Figure 6. Model of the Motivation Complex.

The decider subsystem is placed at the center of each system. The decider receives information about resources from the input transducer and, through the associator, compares this information with values stored in the template. This is the process modeled in Figure 1.

The decision-making processes that were modeled in Figure 2 are shown by reference in Figure 6. The emphasis in this figure is on the external connections to the associator, input transducer, internal transducer, decoder, encoder, and motor subsystems (through the channel and net, not shown). Through these links the decider is able to receive information, make informed choices, and transmit executive orders resulting in motivated behavior. It is also able to communicate with, exercise influence over, and be influenced by other living systems (as modeled in Figures 3, 4 and 5).

In Figure 6 resources from the non-living environment are input at the top and wastes are extruded at the bottom. This represents the process of entropy. Lateral trades of resources between living systems are largely negentropic, as the systems engineer trades that are favorable to each party.

SUMMARY

In this paper we have examined several models that express various components of the process by which living systems are motivated to act. By combining these components into a single model we have revealed the full complexity of the process.

Motivation can no longer be viewed as a simple process by which A stimulates B and B reacts. In some instances it is true that information inputs trigger innate or learned drives that result directly in behavior. Yet in general motivation is a very active and ongoing process whereby living systems continually

• calculate their resource requirements in accordance with their values,

• monitor the living and non-living segments of their environment as well as storage and memory for information about available resources,

• compute what behavior is likely to attain the preferred levels of resources, and

• choose their behavior accordingly.

Furthermore, motivation is a reciprocal process among living systems. The best sources of needed resources are often other living systems. Thus, each system seeks to exercise influence over other systems in order to obtain those resources while protecting its own existing stores. Yet, because living systems usually possess or control resources beyond their immediate needs, trade between systems tends to result in net gains for each.

REFERENCES

Miller, J. G. (1978). Living Systems. McGraw-Hill, New York.

Miller, J. G., and Miller, J. L. (1990). "Introduction: The Nature of Living Systems," Behavioral Science, 35:157-163.

Mitchell, T. (1982). "Motivation: New Directions for Theory, Research, and Practice," Academy of Management Review, 7:80-88.

Murray, H. (1938). Explorations in Personality. Oxford Press, New York.

Tracy, L. (1986). "Toward an Improved Need Theory," Behavioral Science, 31(3):205-218.

Tracy, L. (1989). "Motivational Interaction between Living Systems," Systems Practice, 2(3):333-342.

Tracy, L. (1994). Leading the Living Organization, Quorum Books, Westport, CT

Tracy, L. (1997). "Managing the Costs of Power," Mid-American Journal of Business, 12(1):41-48.

Vroom, V. (1964). Work and Motivation. Wiley, New York.