Back • Return Home

DYSFUNCTIONAL SOCIAL SYSTEMS:

THE CASE OF AID TO REFUGEES IN AFRICA

Andrea G. Tracy* and Lane Tracy

*George Mason University, eMail

Ohio University

Athens, OH 45701

ABSTRACT

Dysfunctional systems may be seen as ineffective or harmful by various of their stakeholders. One example of a social system that may be doing more harm than good is the community of organizations attempting to provide aid to refugees in Africa. Those who are familiar with the plight of African refugees see the situation as becoming worse rather than better. Political instability, warfare, economic collapse, disease, drought, and famine continue to generate new waves of refugees, overwhelming the system that is trying to cope with the problem. This paper presents a pilot study that identifies some of the shortcomings of the current system of aid to refugees. That system is compared with a model of an ideal system in order to identify possible routes to improvement.

Keywords: social system, effectiveness, stakeholder, decider subsystem, refugee

A system is more than the sum of its parts. Some people may interpret this statement as meaning that a system is better than the sum of its parts. Yet that value judgment clearly cannot be sustained. As we look at the world around us we can readily identify social systems that are dysfunctional, at least from the viewpoint of many of the people who comprise them. Such systems may be seen as ineffective or harmful. An ineffective social system is one that routinely fails to serve its purposes or attain its goals, even though it may be composed of talented and dedicated components. The system wastes the resources that are poured into it. And when the system endangers the health or impedes the progress of other systems, those systems are inclined to say that it is harmful.

In deciding that a social system is dysfunctional we must take a viewpoint. We may be looking at the system as individuals, judging whether it meets our needs, wastes our resources, or harms us. Or we may take a more neutral viewpoint, such as the position of the designer of the system, the system’s intended clients, or its suprasystem. In such a case we would be assessing whether the system meets its designed objectives, serves its clients effectively and efficiently, or meets the purposes and goals set by the larger system of which it is a part.

From almost any viewpoint the current system of aid to refugees in Africa is dysfunctional. Those who are familiar with the plight of African refugees see the situation as becoming worse rather than better. Political instability, warfare, economic collapse, disease, drought, and famine continue to generate new waves of refugees. Aid is administered by a community of governmental and non-governmental organizations. These organizations often do not communicate with each other or coordinate their efforts, and they are under no central authority. Host countries are often in dire economic and/or political straits themselves. The forms of aid that are available are, at best, palliative and not aimed at correcting the situation. Corruption and loss of resources is rampant in the system. As a result most refugees live in wretched conditions but have no hope of returning home.

This paper will first try to identify potential causes of dysfunction in social systems, including design failure, subversion, inadequacy of resources, and lack of an effective decider subsystem. We will then examine aid to refugees in Africa as a case in point, describing the system in place and assessing its functionality from various viewpoints. The system will be compared with the template for aid to refugees, as embodied in the charter of the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR), as well as with a model of an ideal system. The paper will conclude with some suggestions for designing a more functional system.

IDENTIFYING SOCIAL DYSFUNCTION

Social systems are a subset of living systems, consisting of groups, organizations, communities, societies, and supranational systems such as the United Nations (Miller, 1978). A living system is characterized by a preexisting template or charter that defines the system’s structure, purposes, and goals, although these specifications may be modified by learning. A living system must also have a decider subsystem "which controls the entire system, causing its subsystems and components to interact" (Miller, 1978, 18). In this paper we will be concerned with organizations, both governmental and private, whose purposes and goals are directed at providing aid to refugees. These organizations form a community which appears to lack an effective decider subsystem.

Some social systems, particularly groups, communities, and societies, occur naturally through some form of autopoiesis. Yet many social systems, especially organizations and supranational systems, are created by design. Such systems are born with overt purposes and goals, thereby permitting a relatively objective judgment as to whether a system is effective, if we are willing to accept the viewpoint of the designer. The values given to the system may be intended to serve the purposes and goals of a suprasystem, in which case the suprasystem may also judge the effectiveness of the designed system. Effectiveness of the system may also be assessed by its components and its clients.

The stakeholder approach is a method designed to assess the effectiveness of a social system (Freeman, 1984; Mitroff, 1983). The stakeholder approach identifies all of the systems that have an interest in the functioning of the given system (i.e., the stakeholders), and then assesses the effectiveness of the given system in terms of how well it meets criteria defined by those diverse interests. It is usually not possible to serve all of those interests equally well. Thus, stakeholders will differ in their assessments of the effectiveness of the system. Nevertheless, a system should serve at least some of the interests of each of its stakeholders. We may, of course, question the bona fides of some stakeholders. For instance, should we credit the judgment of the prisoners as to the effectiveness of a prison? Some would say yes, some would say no.

Assuming that we can agree on the list of legitimate stakeholders, we may employ the following definition of dysfunctionality: If one of the legitimate stakeholders regards the system as ineffective or harmful, it is dysfunctional to some degree. The degree of dysfunction increases with the number of stakeholders who regard the system as ineffective and with the number and importance of interests that are unmet.

Sources of Dysfunction

One common source of dysfunction is the failure of the system to recognize or accept the legitimacy of the interests of some of its stakeholders. A business firm, for instance, may emphasize the interests of stockholders or customers and ignore the interests of employees or the community. The latter groups are then likely to judge the firm to be ineffective or even harmful. A more effective firm would find a way to serve all of these competing interests to some extent, even though they may be incompatible. But first the decider subsystem of the firm must become aware that its effectiveness depends on a broader set of criteria set by a larger set of stakeholders.

Failure to recognize legitimate interests of stakeholders may occur because power and control over the decisions of the system are unequally distributed. This creates a situation of structural violence. According to Galtung (1969) structural violence exists in a social system when "the violence is built into the structure and shows up as unequal power and consequently as unequal life chances...Above all, the power to decide over the distribution of resources is unevenly distributed."

When power is unevenly distributed, some stakeholders are able to capture the primary attention of the decider subsystem and divert resources to themselves. This results in dysfunction from the viewpoint of other stakeholders. For instance, when the highest paid officer of a corporation makes 500 times more than the lowest paid employee, as is true in many U. S. corporations, one has to wonder whether the interests of most employees are being fairly served. And when a corporation conceals information from consumers about safety concerns with one of its products, it seems fair to say that the interests of consumers are not being properly served. Nor does it seem unreasonable to question the effectiveness of a health maintenance organization (HMO) or government health service that routinely refuses to authorize or pay for treatment that has a reasonable chance of saving the life of one of its clients.

Another common source of dysfunction is failure to adapt to a changing environment. A social system that was once effective may become ineffective because its original values do not correspond to the current environment Hospitals today are struggling to remain effective as health care providers in the face of rapid changes in medical technology, new health care delivery systems, rapidly rising costs, and cost containment pressures from insurers and government agencies. Labor unions are laboring to remain relevant in a world in which blue-collar jobs are disappearing, modern human resource practices are undercutting traditional union issues, many workers are temporary or part-time, and the people most in need of union services often cannot afford them.

Inadequacy of resources, as well as inefficient use of resources, may render a social system ineffective. When resources are scarce, the system may fail to meet the needs of any of its stakeholders because it spreads itself too thin, or it may abandon some stakeholders in order to satisfy others. Resources that would ordinarily be used to serve clients may be diverted into an attempt to save the system itself. If that effort succeeds, short-term ineffectiveness might lead to recovery and long-term effectiveness. But the scarcity of resources may prove to be a permanent condition, caused perhaps by the depletion of resources in a given environmental niche, an increase of competitors in that niche, or a loss of paying clients.

The system may suffer from inadequate resources because it is being cut off or squeezed by its suprasystem. This is another manifestation of structural violence in that there is an unequal distribution of decision-making power, thereby causing both the system and its stakeholders to suffer deprivation.

Effectiveness of a system demands that its decider subsystem make decisions that properly balance the values of the system and its stakeholders. The decider subsystem may simply not be up to the task. Many social systems are governed by people or groups who have no training in how to lead a social system, who lack the time or inclination to make decisions for a system other than themselves, who are new and do not know the ropes, who are old and have lost interest, who are corrupt and care only for their own interests, or who are in constant conflict (Tracy, 1994). It may also happen, as in the case that we are about to examine, that there is no central decider subsystem. Decisions are made at lower levels with no top-echelon coordination.

THE SYSTEM OF AID TO REFUGEES IN AFRICA

The seemingly intractable problem of millions of refugees in Africa is not going away. With every day that blood is shed in places like Somalia or Sierra Leone, and with every day that a new conflict emerges, the problem looms ever larger. Unfortunately, the current mechanisms in place to deal with this problem are ineffectual; in some cases doing more harm than good.

We believe that systems theorists and conflict specialists have much to contribute to the refugee issue. Refugees are the people who will (or should) ultimately play a large role in the rebuilding of their war-torn society. If these people are debilitated themselves, through having been victims of humanitarian assistance, the role that they play may provide impetus for the re-emergence of strife.

The Research Problem

The pilot study outlined herein was conducted in order to address a threefold, causally related question. We attempted to ascertain (1) whether or not the inhabitants of typical refugee camps in sub-Saharan Africa are victims of structural violence. If so, we wanted to know (2) whether such violence adversely affects efforts toward peace building when these refugees are repatriated to their respective countries of origin. Finally, we sought to learn (3) whether there exists an alternative to existing systems of aid to African refugees with a focus on the empowerment of the individual.

Significance of the Problem

It is critical to address the problem at hand for several reasons. To begin, there is an ever-growing population of refugees globally due to the increase in internecine wars following the end of the Cold War. This growing population must be dealt with, for humanitarian and practical reasons. At the practical level, the very existence of refugee populations and migrations is said to further exacerbate regional tensions (Maynard, 1999). From a humanitarian perspective, it is difficult for us as humans to sit by and allow people to suffer unnecessarily. This discomfort was evidenced by the recent outpouring of worldwide sympathy and consequent assistance towards the Kosovarian refugees.

Secondly, the resulting growth of the refugee population places a large demand on the United Nations, as the responsibility for protecting and caring for such people rests largely in the mandate of the UNHCR. The UNHCR was founded in 1951 as a means to resolve the situation of some 400,000 European refugees left over from World War II (Gorman, 1994). While its initial mandate was for only three years, that mandate has obviously been extended. What is not widely understood, either by laymen or those working within the system, is that UNHCR is not itself an implementing agency. UNHCR simply raises money from UN member governments which it then passes on to charities contracted to do the actual fieldwork (Hancock, 1989). UNHCR itself is meant to protect refugees, and to seek permanent solutions; but as such the agency has no formal budget for either activity. It therefore relies on the other non-governmental organizations (NGOs) or sister UN agencies (UNAs) for implementation, while remaining "in charge." If there is a central decider subsystem for the system of aid to refugees, it is the UNHCR.

Thirdly, nations are becoming increasingly reluctant to act as hosts to refugee populations. There is said to be a high level of crime, domestic violence, prostitution, alcoholism and drug abuse in camps or in areas where refugees have settled (Gordenker, 1987). It is not difficult to imagine why this should be the case, considering the large number of young males and females, deprived of education, the means to recreation, and productive activities, who make up a major portion of such populations. Host nations, many of them plagued with development issues in need of immediate attention, have neither the time nor the resources demanded by refugee populations and the international organizations working therein.

The case of Kenya offers an illustration of this situation. Kenya has served as a host to many different groups of refugees, including Somalis, Ethiopians, and Sudanese. Over the years the camps that housed this diverse and large populace have shrunk from eight to one. The one still remaining, Kakuma, is known as ‘the other side of hell’ amongst refugee communities in the area. Set in the arid northern desert region of Kenya, Kakuma houses approximately 90,000 refugees from different areas. The conditions are deplorable to the point of being inhumane. Strife between the various groups is constantly evincing itself, in some cases mirroring the causes of war in the first place (e.g., Sudanese Christians fighting Somali Muslims). Simultaneously, the Kenyan authorities have been systematically and cruelly expelling those refugees who have settled independently within its cities. This phenomenon is particularly evident in the neighborhood of Eastleigh in Nairobi. Raids conducted by the police have reached an almost daily level of occurrence. If those being raided do not have enough money with which to bribe the police, they are put in jail. UNHCR does not fulfill its mandate of protection in these cases, as there are simply too many cases in too many places to respond to.

Fourth, the existing mechanisms for dealing with refugees, both in terms of camps and repatriation, have proven ineffectual. This seems true particularly in the case of Africa. "Indeed, Africa's refugee crisis has continued to worsen while the prospects for development have receded in the face of war, famine, debt and environmental deterioration" (Adelman & Sorenson, 1986, 175). Camps are simply proving ineffectual in the face of a growing crisis. Initially, camps were meant to be temporary settlements for those fleeing their war-torn homelands. "Refugees are, in contrast, viewed as a temporary phenomenon, and money given for their assistance falls under emergency relief - a budget line on a par with an interstellar black hole" (Harrell-Bond, 1986). In many cases, and for many reasons, the camps have turned into permanent settlements, but without the infrastructure to make them viable.

Finally, if it were revealed that refugees who repatriate after having lived in camps serve as impetus for the re-emergence of conflict, there would be critical implications for the fields of conflict resolution and peacekeeping.

Theoretical Setting

Systems theory revolves around the notion that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. In living systems the parts are constantly seeking equilibrium or harmony among themselves. Non-normative events or arrangements are said to produce stress, which will eventually result in conflict. Furthermore, systems 'operate with circular causality', with conflict occurring in chain reactions (Wilmot & Hocker, 1998; Hartmut, Klaczko, & Muller, 1976). This suggests that the ‘returnee’ population will necessarily have an effect on the nation to which they are returning, as they will come to constitute one of its 'parts'. Whether their reintegration leads to equilibrium or discord in the system is related to a myriad of factors; economic, interpersonal, interactive, and psychological. Should the process of re-integration prove disruptive to the system, we can predict the return of conflict. This theory is further relevant considering the rise of what many analysts are calling ethnic or identity-based conflict (Maynard, 1999; Crocker & Hampson, 1996). Such conflicts can be said to find their inception at the grassroots, among the component parts of the society.

Concepts and Terms

There are a few concepts that bear examination before we can proceed, as well as a few definitions. The term refugee itself requires a closer look. As defined by the 1951 UN Convention "Relating to the Status of Refugees," a refugee is "anyone who, owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such a fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country (Gorman, 1994, 29)." Essentially a refugee is a displaced person, either internally (remaining in the country of origin but having fled their home) or externally (those who have left their country of origin altogether). For the purposes of this paper, we are addressing externally displaced people exclusively.

The refugee concept is too often equated with the idea of the victim. This causes refugees to be conceptualized as essentially recipients of action rather than actors. "They are seen, and may therefore come to see themselves, as populations whose lot it is to be counted, registered, studied, surveyed and, in due course, hopefully 'returned', at which point they become 'ordinary people' once again" (Allen, 1996, 34). The viewpoint inherent in this definition is at the core of the paradigm guiding refugee aid work today. Refugees are no longer seen as people, and are therefore dehumanized.

The implicit logic behind the very definition of refugee is that land, or home, defines a person or people. As these people are stripped of their land, they are stripped of their identity. Further, there is a great deal of stigma attached to the term for refugees themselves, as it is equated with that of the helpless victim in need of assistance. This in turn increases UNHCR's difficulty in keeping track of the population they are meant to be protecting. People move continually, in and out of camps, in an effort to avoid such stigma. The perception in some cases, in fact, is that once their name is put on paper, they are identifiable, locatable, and are therefore a potential target for the antagonists they sought refuge from in the first place (Keller, 1975). In order to maintain coherence for the purposes of this study, we are forced to retain the word refugee; using it to denote people who have fled their homeland to another country in an effort to seek refuge from persecution and possible violence.

Repatriation should be clarified, as its pure definition varies so often from its reality. As espoused by UNHCR, repatriation is meant to be voluntary, taking place only when certain conditions and agreements are taken amongst the UNHCR, host nations, and nations of origin (Adelman & Sorenson, 1994). This in itself is problematic in that the opinions and desires of the refugees are not taken into consideration at all. In Africa repatriation is more often refoulement, or forced return. Furthermore, while repatriation is the primary mandate of UNHCR, it is not for all that comprise the refugee population, as many refugees are migratory by nature and have no intention or desire to return.

Here the concepts of empowerment and human agency are addressed. The notion of human agency is largely predicated on the ability of an individual to control and create his or her 'life-world'. Empowerment, on the other hand, is the enabling of individuals to have control over their respective lives. The issues of agency and empowerment are particularly relevant and important in the consideration of refugees, as they are in positions that "fall out of the national order of things (Malkki, 1995)." This position of liminality results in the regarding of refugees as subjects to be acted upon, as opposed to actors. This issue becomes particularly salient when speaking of refugees who live in camps, as such camps can be considered distinctly controlled and regulated spaces in the Foucauldian sense. These issues will be expanded upon in the following pages.

Next we must address the concept of empowerment, or humanization. Humanization rests largely on the concept of identity. Our identity, whether collective or individual, is the combination of how we see ourselves and how others see us. It is built up over years and therefore contains many interdependent and connected layers. When we lack in identity, we lack in a sense of purpose, of belonging and acceptance, of autonomy and self-efficacy. These are considered our basic human needs. When we lack in identity, we essentially lack in what it is to be human on a psychic level. Thus, when we speak of empowerment, we speak of the recapturing of identity.

Specific Questions

The study set out to address several specific questions. First, an overall picture of settlements in sub-Saharan Africa had to be constructed through both a survey and a literature review. In this vein, several things had to be examined: 1) the existing structures and mechanisms of the camps, 2) the resources available to the aid workers, 3) the general attitudes of those workers, 4) the mandates of the organizations involved in refugee work, 5) the cooperation amongst such organizations, and 6) the existing paradigms of aid extending throughout both the organizations and workers. Through an examination of the above, we were attempting to determine whether or not structural violence does exist in most refugee settlements within sub-Saharan Africa.

Our next goal was to reach an understanding of the possible psychological effects that living in such settings has on the inhabitants. This was investigated through both interviews and literature review. In order to ensure that those effects were directly related to camp habitation, we simultaneously studied refugees who did not settle in the camps.

Third, we examined the issues surrounding repatriation, ultimately attempting to determine the effect that such population movements would have on war-torn communities and states. Fourth, we set out to make a prediction as to whether or not those who settled in camps were likely to have a negative impact on their home country upon repatriation, possibly providing the impetus for the re-emergence of conflict. Finally, we hoped to provide the foundation for new policy regarding refugees.

Units and Level of Analysis

As there were two initial questions to be addressed, there were two sets of independent and dependent variables utilized in conducting the survey and interviews. In terms of the first question; the existence of structural violence in camps and the effects of such violence on refugees, the state of the refugees was the dependent variable and the environment of the camps the independent. The control variable in this respect was the state of the refugees who did not settle in camps, but settled independently instead.

In terms of actors, the first author looked from an intra-psychic level at refugees from Africa who had immigrated to the United States. Africa was chosen as the region of origin for several reasons. Due to what appears to be an increase in the spread of new conflicts, as well as the protraction of already-existing wars on the continent as a whole, there has been a corresponding rise in the number of refugees in Africa. With this significant increase in the refugee population has come an increase in the number of refugees granted resettlement in the United States. This allowed us to gather a somewhat representative sample, although not fully representative considering the immensity of the African continent and the diverse population it houses. Finally, as the first author spent several years working in the 'refugee business' in Africa, we are familiar with many of its relevant aspects.

In terms of the independent variable, the operation of the camps themselves, we chose to look at the overarching paradigm at work, the service such camps provide, the structures operating therein, and the aid workers involved. With the control group, the refugees who did not settle in the camps, we were attempting to discover how their experience of displacement was different from those who had settled in camps. In doing so, we were attempting to discern what effects were due to the camps, and what effects occurred simply by virtue of a life displaced.

As for the second question; how refugees who were repatriated ultimately affected their countries of origin upon return, the responses of the refugees became the independent variables while the conditions of the countries of origin were the dependent.

The Pilot Study

The study reported here is a pilot study for a multilevel, multi-modal, amalgamated research project. The study is exploratory, in that to our knowledge work has not been done on this topic to date; descriptive in that it attempted to explain the phenomena; and predictive, in that it tried to predict future events. With this in mind, we used various methods of data collection in an effort to maximize efficiency and generalizability. In terms of the first set of independent and dependent variables, that of the effect of the camp on the refugees, we utilized the information that the first author gathered from interviews and questionnaires, coupled with personal observation and a literature review. In terms of the second set of variables, the effect that the returning refugees would have on their home country, we employed literature review and extrapolation.

The study set out to test the following hypotheses:

H1: Structural violence is built into the processes by which refugee settlements operate.

Structural violence in the settlements will erode already-vulnerable psychological processes. Frustration and anger will increase as a relative deprivation is realized (Sandole, 1999). Frustration will only marginally evince itself in the form of small fights and protests, as the inhabitants are dependent on the aid allocated by the structure. Thus, it will be further inhibited from expression and will build further (Dollard et al., 1939).

H2: This structural violence, enacted upon a populace in flight from perhaps both physical and structural violence in their home country, manifests itself in increased frustration and anger within the refugee population.

Upon repatriation or refoulement (forced repatriation), returnees will be offered little assistance or opportunity for the rebuilding of a life; thereby increasing their deprivation. As the society into which the returnees are returning is vulnerable itself, both socially and structurally, the mechanisms necessary for containing and preventing conflict are not in place or are weak. As time marches on and little change or progress can be seen on the individual level, frustration increases. Because peace-building efforts are often coupled with the presence of foreign military troops, however, the frustration may be inhibited from expression yet again. This emotional buildup is compounded by the enormous psychological burden of returning to the 'scene of the crime' so to speak.

H3: Frustration and anger increase when refugees return/are returned to their home country.

Finally, upon the inevitable departure of peacekeeping forces, the frustration will have the opportunity to manifest itself in the form of aggression.

H4: Conflict reemerges in the home country when refugees are repatriated.

Collection of Information

We chose to utilize the focused interview format, as it allowed us to obtain "details of personal reactions, specific emotions, and the like" (Nachmias and Nachmias, 1996, 235). Ultimately, the questions were designed to elicit an understanding of the different experiences of those who had settled in camps and those who had not. Due to the problems of access referred to earlier, we were forced to utilize questionnaires as well as interviews. We decided to combine the data gathered from the two sources, as the interviews essentially followed the same format in written form. As the sample was so small, we felt that statistical analysis would prove irrelevant, but that some inferences based on the combined responses could be made nonetheless.

The survey sample consisted of eleven respondents altogether, three of whom were interviewed, and eight of whom responded to a questionnaire. The respondents came from the countries of Somalia, Liberia, Sierra Leone and Ethiopia -- seven were men, and four were women. There were three groups of people altogether: those who had settled in camps and remained there (even if they were moved from one camp to another); those who had settled independently, but remained as refugees; and those who had settled both in a camp (s), and independently.

Due to the fact that the questions were open-ended, as well as the fact that such a small sample was obtained, we felt that statistical analysis would prove irrelevant. It was still

possible, however, to make inferences based on the responses as to some differences between those who settled in camps and those who did not, as well as to ascertain to an extent (albeit limited) the effects of camps on people. It would therefore be beneficial to provide a breakdown of the questions, look at the variation of responses, and attempt to determine some relationships and make some tentative generalizations.

Results of the Interviews/Questionnaires

Question 1--Camp/self-settled: As was previously mentioned, 4 settled in camps, 4 did not, and 3 settled in both. Where: All were externally displaced. Time: All remained in their respective places for a period of time exceeding three years. If left, why: Group I--forced to change camps due to closings; Group II--none moved; Group III--left camps when other means were located/earned

Question 2--Why did you settle where you settled: Group I--no other choice; Group II--choice; Group III--combination of the two

Question 3--only 4 of all group members across the board had family and friends where they went. It did not seem to have made much of a difference in their choice, as it was

more a result of chance and luck

Question 4--Assistance: All eleven individuals received assistance from UNHCR; members from Groups I and II also received assistance from external sources (i.e. family abroad, etc.)

Question 5--Overall feeling about the assistance: members of all groups felt it to be insufficient. The majority expressed what they conceived to be a 'gradual decline' over

the years

Question 6--Safe--Overwhelming 'No!' Reasons given: Group I--rebels come across the border and kidnap/rape/get recruits; Group II--rebels all around, indigenous community members; Group III--both reasons apply

Question 7--Spend the day--Group I--waiting, cooking, nothing; Group II--looking for work, school, working; Group III--combination of the two, with the addition of 'looking

for way out'

Question 8--Opportunities: Group I--2 had none, 2 worked as translators, one of whom also taught school; Group II--difficult but possible to find work--depended on you; Group

III--combination of the two

Question 9--Community: Group I--many people, competitive, inhumane; Group II--bad because not liked/accepted by indigenous people; Group III--when asked to compare, all three said the camp was inhumane but better in a way because members of their community were there

Question 10/11--hope/change--majority of both groups maintained they always had hope and still do, but their countries are 'not good now'

Question 12--power/independence/charge of life--Group I--overwhelming no; Group II--yes, because got to live alone and 'make own way'; Group III--compare--in camps, definitely no, self-settled, yes

Question 13--would have changed: Group I--never would have lived in camp, would have improved assistance; group II--no war in the first place, better assistance; Group III--similar

Assessment of the Results

In regards to all three groups, the responses were rather similar. Life is not good in the camps, life is not good outside of the camps--life in general is pretty tough when you are

displaced. Those who had settled in camps painted a much grimmer picture, however: "There was sickness and pain all around. We had to compete for assistance, had to fight to survive. We were grouped together like animals and given nothing to do but sit and wait for something better" (interview, 1999). Some of the refugees questioned were forced to move from camp to camp due to the frequent closings, "...like cattle going from place to place...we continually had to remake whatever life we could find" (interview, 1999). Ultimately, whoever could get out of camp settlements did so. This meant obtaining means from the outside, however; usually through either a successful relation or illegal means.

Those who settled independently struggled as well. Integration into the community in which they lived was difficult. While initially many communities' inhabitants seemed to welcome the displaced people and offer them sympathy, the longer they stayed, the more likely those attitudes tended to take a different turn. The refugees came to be seen as competition for scarce resources such as jobs and food. They came to be seen, essentially, as invaders.

Research in terms of literature review proved very insubstantial, resulting in a piecemeal effort. "Why is there no tradition of independent, critical research in the field of refugee

assistance analogous to that for development studies? It is assumed that the impact of development projects will be evaluated, but humanitarian programmes have never been subjected to the same scrutiny. As one observer put it, 'Refugee organisations are becoming more and more an almost impregnable system, protected by the strong shell of their mandate to dispense what is regarded as 'charity'" (Harrell-Bond, 1986, xii).

Structural Violence in Refugee Camps

In terms of the first hypothesis about the existence of structural violence in settlements, both the interviews and literature review shed light. According to the refugees, there is

definitely structural violence. The refugees asserted that they had virtually no say in the distribution of scarce resources allowed them. According to Maynard (1999, 8), "...refugee camp living is usually anything but healthy. Though physical needs are generally accommodated, the relatively languid environment of a camp usually offers little in the way of productive activities."

Attitudes and Mandates of Aid Workers

"Those working in the field have a difficult time escaping the effects of compassion fatigue often attributed to humanitarian assistance. Field staff are overworked and they are not trained to cope with most of the individual problems which present themselves...The frustration of the fieldworkers, which arises from a general sense of inadequacy, may account for the hostility which one so frequently observed in their relations with refugees" (Harrell-Bond, 1986, 302).

From personal experience, the first author has met with both hardened and hard-working program and protection officers. Those who make up the hardened group seem to feel more sympathy for themselves than for the refugees they are meant to be helping. In an effort to alleviate any guilt that may arise from such an outlook, they tend to regard all refugees as dramatic liars and hucksters. Unfortunately, the latter group of hard workers is less prevalent. Rather than direct their frustrations at the refugees themselves, these people develop a peculiar (however understandable) rage toward the organization for which they work--the bureaucracy therein, and those who sit on their proverbial asses in their air-conditioned offices declaring their great contributions to humankind. While this rage serves to galvanize great amounts of dedication and effort for the refugees, it also means that these workers look to be about ten feet from the grave. Understandably, they do not tend to last very long in the refugee business.

Cooperation amongst Organizations

Generally speaking, standards of supervision provided by UNHCR are incredibly slack. There exists

...a dearth of vertical -- as well as horizontal -- communication (which) often leads to a breakdown in information-sharing and discourse on international assistance, both within and between organizations and interest groups...As a result, programs and policies directed form the center may not be appropriate to existing conditions, or, worse, they may even prove harmful. (Maynard, 1999, 3)

As one of our interviewees put it, "there are a whole bunch of people trying to do good for us...but they are all young and have no experience...and whatever they want to do is

not what their people at home want them to do...so they make promises and they can't come through."

With the growing number of refugees is an accompanying proliferation of aid organizations involved in humanitarian assistance. The lack of coordination and communication, and ultimately of competence, can prove very harmful indeed. This lack is fostered by the fact that NGO's are independent by nature and prone to believing their mandate or course of action is superior.

Paradigm Shift

With the shift towards post-modernity and an increasing awareness of the deficiencies inherent in the existing system; there is a growth in discourse on the need for a shift from

development geared towards 'us-doing-things-to-them’ to grass-roots participation and sustainability. The Declaration and Programme of Action, set out in 1984 at the International Conference on Assistance to Refugees in Africa (ICARA II), stated that: "assistance...should be development oriented as soon as possible..." (Allen, 1996, 18). In other words, assistance should work towards the empowerment of refugees by securing their productivity and self reliance. Unfortunately, it has been rhetoric to date. Such rhetoric, by virtue of having been spoken, actually serves to decrease the chances of real action being taken. A change in action must be accompanied or even precipitated by a change in attitudes, or paradigm shift. Such a shift is not easily made. Humanitarian-based aid has for too long languished in its moral standing as the bastion of good works. In order to galvanize a shift in attitudes, there must be a profusion, a veritable bombardment of data geared towards revealing the inadequacies of the systems at work.

Psychological Effect of Camps on Inhabitants

"It is certainly possible that not only the loss of professional status, but the loss of power and autonomy in the settlement programme may 'slow down or even reverse the process

of gradual psychological recovery from the massive trauma of war" (De Wall, 1993, 21). One of our interviewees asked, "have you ever been in a situation in which everything you had ever known was lost to you? Your home, your family members, your life as you knew it? Because under such circumstances you are in a daze. You don't know who you are, you don't know what sex you are, and to care again is the hardest part" (interview, 1999). The man speaking was one of those who had initially settled in a camp, 'found his ground' and then gone in search of greener pastures. He came around to saying that the whole experience had afforded him a new lease on life, in which he learned to appreciate the things that mattered. But that was only because, as he said, he was allowed to get out of the camp and figure it out for himself. The majority of refugees are not so fortunate and are forced to remain in the camps for long periods. They become numbers as opposed to people; their sense of society is distorted and transforms into something ugly.

We must as well consider the trauma associated with having to flee from war, and the fact that this trauma is not dealt with in the camp setting at all. Crisis theory explains the

response of individuals to stress by focusing on the crisis situation that causes stress. As Baker (1984) says:

One may link crisis theory to refugee experience in the following way. Stress is an inevitable consequence of being uprooted. If the refugees' coping skills are good and if an environment is provided that ensures basic survival needs are met, if there is a real hope for a better future, the stress remains manageable...If neither of these conditions exist, then the stress level can rise rapidly and the person shifts into a state of unrelieved crisis. Research done in terms of trauma experienced by victims of war anywhere other than in western nations is practically nonexistent. Consequently, there have been no efforts made in terms of psycho-social healing for refugees on the parts of international organizations.

Finally, Kim Maynard (1999) asserts:

Another potential problem stemming from long-term assistance to displaced populations is its tendency to encourage dependence on outside sources and, thus, to discourage self-reliance, motivation, and self-esteem. This dependency can have serious long-term repercussions on community rehabilitation, not the least of which is the diminished potential of

individuals to reenter society as self-sufficient, productive members.

Repatriation

Repatriation is the primary aspiration for all agencies involved in refugee assistance. This is essentially a policy built on pragmatism, as the chances for substantial resettlement

both inside and outside of Africa are significantly remote. Unfortunately, repatriation is often carried out for the wrong reasons (e.g., conflict breaking out in the host country) and

in ways that do not imply voluntary consent.

The first author had the following experience: Two years ago in the Ivory Coast I witnessed the undertaking of a repatriation exercise. According to the Ivorian government, it was time for the Liberians to go home. I remember watching a family who refused to go, because they had heard that there were 'secret killings' occurring in Liberia. The UNHCR security guards responded by taking the children of the family from their parents forcibly and placing them on the trucks amongst the rest of the returnees. With great resignation, the parents eventually boarded the truck lest they be separated permanently from their children.

Maynard (1999, 38) observes that: "Research and field observation reveal that returnees face not only financial challenges and struggles to reestablish living quarters, occupations,

and relationships but also the potential of targeted oppression. At the same time, the receiving communities confront increased contention, competition, and uncertainty."

The above factors lead most returnees to depend on material assistance. As such, however, UNHCR's mandate in terms of return still officially only extends a small step beyond resettlement, leaving a significant gap in assistance during the transition period. The usual assistance offered to returnees is in the form of food, household items, and

agricultural tools. In the face of a devastated economy and infrastructure, the lack of a viable government force, and the continued disarray of social affairs such assistance will

only take the returnees so far. Finally, it should be mentioned that returnees are often viewed as people who "abandoned" their home and fellow countrymen in a time of turmoil. This can in some cases lead to issues of persecution, both physical and psychic.

Finally, as stated by Maynard (1999):

whether the return process contributes to a restoration of normalcy or leads to further destabilization appears to be in part determined by the economic conditions of the receiving community. In areas where basic needs and living standards are met, the return of displaced populations seems to represent a welcome and vital ingredient to pacification...The other extreme occurs under conditions of intense competition for resources and employment and massive infrastructure damage. Communities struggling with a floundering economy and damaged traditional methods of livelihood are understandably more prone to harbour inter-group hostility and resort to scapegoating. Unfortunately, most contemporary returns

occur under circumstances closer to the latter extreme than to the former.

In light of the above answers to our initial questions and hypotheses, we believe we can accurately predict that returnee populations coming from camps will serve to disrupt the

system and possibly lead to conflict re-emergence in the home country. The question then remains, where do we go from here?

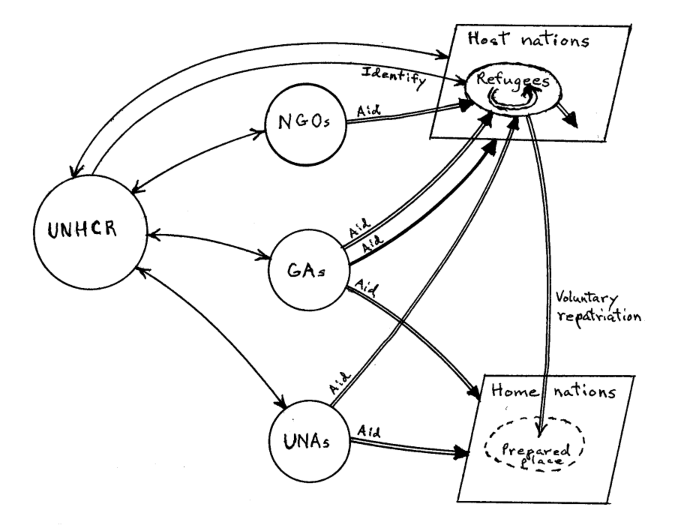

A MODEL

Soft systems methodology (SSM) recommends that a useful procedure is to build a model of the desired system and compare it with a rich picture of reality (Checkland & Scholes, 1990). Parts of the model in this instance are suggested by the mandate of the UNHCR. Ideally, aid to a group of refugees is a system in which a variety of United Nations agencies (UNAs), governmental agencies (GAs), and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) act in a coordinated fashion to (1) identify a group of bonafide refugees (as opposed to migrants, outlaws, etc.), (2) serve as intermediaries with the host nation, perhaps providing assistance to that nation to ameliorate the impact of the refugees, (3) provide emergency food, clothing, and shelter to the refugees, (4) help the group to help itself over a longer period, if necessary, (5) prepare the group for voluntary repatriation. To these steps our analysis suggests that the following should be added: (6) prepare the home country to repatriate the refugees, and (7) assist the refugees, both materially and psychologically, in the process of reintegration into the home nation. Figure 1 provides a rough, but hopefully rich, picture of the model.

Figure 1. Rich Picture of Model Refugee System

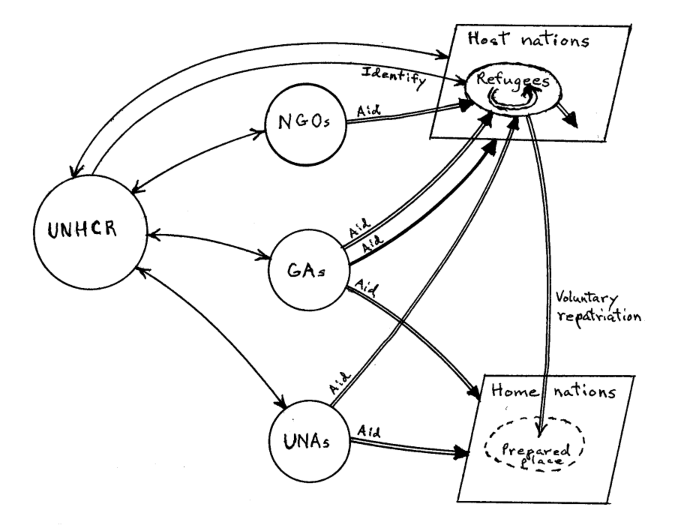

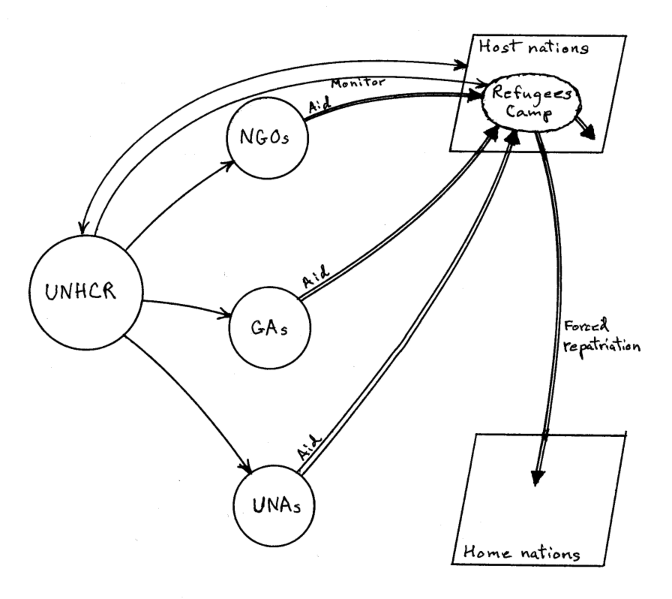

The results of our pilot study indicate that reality departs from this model in several respects. Although the UNHCR identifies groups of displace persons, there is little effort to screen them to find out if all are truly refugees. The UNHCR does little to coordinate the efforts of UNAs, GAs, and NGOs. Aid is focused on the body of refugees, mostly ignoring their impact on the host nation. Sometimes the group is aided, through training and provision of tools, to help itself while waiting for repatriation; sometimes it is not. Virtually nothing is done to prepare the group or the home country for repatriation. Meanwhile, some refugees leave the camps and resettle themselves. Thus, reality appears as in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Rich Picture of Current Aid System

The model in Figure 2 is deficient in feedback and fails to meet some of the needs that have been identified. What can be done to bring reality closer to the ideal model?

RECOMMENDATIONS

First, in terms of the overarching system there must be a shift toward coordination, communication, and collaboration among UNHCR, involved NGOs, host governments, and the refugees themselves. Furthermore, as was indicated earlier, the fact that the 'refugee problem' is not going away anytime soon must be taken into consideration and a paradigm shift must be adopted accordingly. Finally, there must be more research done in relating to the psychological effects of refugee camp life and how issues of war-related trauma can be addressed in the camp context.

A possible course of change geared towards empowerment of refugees is as follows:

• To begin with, refugees should not be made to settle in camps in order to be granted protection by UNHCR. Those refugees who decide and are able to live outside of camps should be afforded protection rights.

• For those who choose to settle in camps, for whom the prospects of repatriation are remote, the settlements should change structurally to be based on the type of society that the refugees are used to, such as a communal farming society.

• Those who opted to settle therein would have the following options: receive a plot of land, seed, and tools; or do professional work in the camp (i.e. teacher, builder, engineer). Much like a kibbutz, all products and resources would be available equally to the inhabitants. Those who could not work, for reasons deemed legitimate, would be offered assistance from the community.

Some 200 rural development schemes for refugees have been attempted throughout Africa since 1961. Rural settlements are considered a high priority for both government and international aid. The aim of the settlements is that they reach a point of self-sufficiency, be cut from international aid ties, and ultimately become integrated into the local administrative framework of the host country. Unfortunately, for reasons such as poor geographic locations, non-arable land, polluted water, and land capacity reaching its limits, the majority of these settlements do not reach the envisaged level of self-sufficiency and are abandoned. Furthermore, host governments have not generally been offered ample incentive for allowing such settlements to exist on their land.

When such settlements do work, however, they are unparalleled. The first author visited such a settlement in western Uganda; in which Rwandese, Sudanese, Burundians, and Zairois lived together peacefully. Each family had been allocated a plot of arable land; the school was locally run, former teachers were teaching, and health services were available.

It is our full conviction that carried out properly, such settlements can and do work, both tangibly and in terms of promoting individual empowerment. Before we can move toward such a model, however, there must be a paradigmatic shift in terms of how assistance organizations view refugees and aid to them. Refugees must come to be viewed as people, as opposed to victims and objects, and must therefore be included in the process of deciding the course of their lives. Should they be allowed to do so, they will be afforded the further luxury of retaining their respective 'life-worlds', and ultimately, of reshaping their countries of origin upon return.

REFERENCES

Adelman, H., and Sorenson, J. (1994). African Refugees: Development Aid and Repatriation, Westview Press, San Francisco.

Allen, T. (1996). In Search of Cool Ground: War, Flight & Homecoming in Northeast Africa, First Africa World Press, London.

Baker, R. (1984). "Is Loss and Crisis Theory Relevant to Understanding Refugees in Africa?" Unpublished paper presented to a meeting on the psychosocial needs of refugees, 22 June, Refugee Studies Programme, Queen Elizabeth House, Oxford.

Checkland, P., and Scholes, J. (1990). Soft Systems Methodology in Action. Wiley, New York.

Crocker, C. and Hampson, F. O. (1996). Managing Global Chaos: Sources of and Responses to International Conflict, United States Institute of Peace, Washington.

De Waal, A. (1993). "War and Famine in Africa," IDS Bulletin, 24(4):33-40.

Dollard, J., Doob, L., Miller, N., Mowrer, O., and Sears, R. (1939). Frustration and Aggression, Yale University Press, New Haven.

Freeman, R. (1984). Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach, Free Press, New York.

Galtung, J. (1969). "Violence, Peace and Peace Research," Journal of Peace Research, 6(3):167-191.

Gordenker, L. (1987). Refugees in International Politics, Columbia University Press, New York.

Gorman, R. (1994). Historical Dictionary of Refugee and Disaster Relief Organizations, The Scarecrow Press, London.

Hancock, G. (1989). Lords of Poverty: The Power, Prestige, and Corruption of the International Aid Business, The Atlantic Monthly Press, New York.

Harrell-Bond, B. (1986). Imposing Aid: Emergency Assistance to Refugees, Oxford University Press, New York.

Hartmut, B., Klaczko, S., and Muller, N. (1976). Systems Theory in the Social Sciences, Birkhauer Press, Basel.

Hocker, J., and Wilmot, W. (1998). Interpersonal Conflict, McGraw Hill, Boston.

Keller, S. (1975). Uprooting and Social Change: The Role of Refugees in Development, Manohar Book Service, New Delhi.

Malkki, L. (1995). Purity and Exile: Violence, Memory, and National Cosmology Among Hutu Refugees in Tanzania, University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Maynard, K. (1999). Healing Communities in Conflict: International Assistance in Complex Emergencies, Columbia University Press, New York.

Miller, J. G. (1978). Living Systems, McGraw-Hill, New York.

Mitroff, I. (1983). Stakeholders of the Organizational Mind, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco.

Nachmias, C. F., and Nachmias, D. (1996). Research Methods in the Social Sciences, St. Martin's Press, New York.

Sandole, D. (1999). Capturing the Complexity of Conflict: Dealing with Violent Ethnic Conflicts of the Post-Cold War Era, Pinter, London.

Tracy, L. (1994). Leading the Living Organization, Quorum, Westport, CT.

Wilmot, W., and Hocker, J. (1998). Interpersonal Conflict, 5th Ed., McGraw-Hill, Boston.