Back • Return Home

DYSFUNCTIONAL SOCIAL SYSTEMS:

THE CASE OF HEALTH CARE INSURANCE IN THE U. S.

Lane Tracy

Copeland Hall, Ohio University

Athens, OH 45701

ABSTRACT

Efficiency fosters the survival of living systems. Yet inefficient social systems abound in our world. How do inefficient social systems come to exist and why do they survive? The community of insurers, government agencies, insurees, and health care providers who are linked by the current system of health care insurance in the U. S. is examined in this paper as a case study of an inefficient social system. Soft systems methodology is employed to compare the current system with an ideal model, and recommendations are offered as to how to move toward that model.

Keywords: social system, efficiency, health care, insurance, model

Efficiency is an important factor in the survival of living systems. Miller (1978, 41) defined efficiency of a living system as "the ratio of its performance to the costs

involved." He hypothesized that "Systems which survive make decisions enabling them to perform at an optimum efficiency for maximum physical power output, which is always less than maximum efficiency" (Miller 1978, 101). In general terms a living system is more likely to survive the greater is the worth of its outputs in comparison to the worth of its inputs, where worth lies in the ability to command resources.

When we look at the social systems (i.e., groups, organizations, communities, societies, and supranational systems) in place in our world, we often see systems that seem inefficient. That is, we can imagine social systems that could accomplish the same ends at less cost or could produce greater worth for the energy that is being expended. This may cause us to wonder (1) why these seemingly inefficient systems were designed that way and (2) how they continue to survive.

Some possible answers to the first question would be that (a) the system was not designed that way but evolved through adjustment processes into its current state, (b) the system is

a relic -- its outputs were of greater worth or its inputs were less costly when it was first created, or (c) the system is part of a suprasystem whose overall efficiency is great enough to tolerate inefficiency in some of its component parts. As an example of the first case, consider the health care insurance industry in the United States.

An industry is a living system in the form of a community of organizations. The U. S. health care insurance industry is composed of private insurance firms and agents, governmental agencies, health maintenance organizations (HMOs), and employers, with providers (hospitals, physicians) and consumers as adjunct systems. As is true of all kinds of insurance, the health care insurance industry was originally developed to provide a mechanism for coping with catastrophic loss by pooling assets and risks. Yet competitive pressures and other forces have driven the industry to provide insurance policies that cover minor risks and the expenses of routine procedures. In this latter endeavor the industry has proven to be quite inefficient (Vogel & Blair, 1975). For many of those risks and expenses it would be much more efficient to avoid the paperwork and simply pay the costs out of pocket.

An example of the second case might be labor unions. When they reached their peak in the United States in the 1930s through '50s, there was a great need for them because of the rapacious labor practices of many employers. Although unions added a costly intermediary to the relationship between employees and employers, union services were very valuable to employees because a union greatly increased employees' bargaining power, which in turn enabled them to raise their wages and improve their job security. Incidentally, one of the great successes of labor unions in the U. S. was to obtain health care insurance as a benefit not only for employees but also for their families. As employers changed their human resource policies in the direction of greater consideration for the needs of employees, the worth of the service provided by unions decreased, while the costs of their growing bureaucracy increased. Today many Americans regard labor unions as relics, although it can be argued that if unions did not exist employers would quickly return to their old ways.

The U. S. Social Security system, including Medicare and Medicaid, seems to be an example of the third case. As with almost any government bureaucracy these programs provide a relatively small (and decreasing) benefit at a rather high (and increasing) cost. Yet the Social Security system is part of the "safety net" of a much larger entity, the U.S. government. That safety net is important in maintaining the confidence of citizens in their government. The costs of loss of confidence, as well as the expenses of caring for those who cannot afford to care for themselves, could be much greater than the excess costs of Social Security. Thus Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are sustained by the "full faith and credit" of the U. S. government.

Here we have also one possible answer to the question of how inefficient systems survive. Many such systems are propped up by other systems. Our relatively inefficient postal system is subsidized by the government. Inefficient manufacturing organizations are protected by tariffs. The health care insurance industry is aided by federal tax incentives and by a federal bureaucracy that sets price standards for medical services.

Another answer to the question of survival is illustrated by the following story. I use many case studies when I teach management courses, and these cases usually describe business firms that are in dire straits. Students often ask me how such organizations ever managed to survive with so many obvious problems. My answer is: "You should see their competitors." Inefficient systems often survive because within their particular niche they are no less efficient than those that might put them out of business. This raises the further question: How can a whole group of inefficient systems arise together? How can a whole industry be inefficient?

In this paper other causes of inefficiency will be examined, as will the question of how inefficient social systems survive. The health care insurance system in the U.S., including individual, group, and government-funded insurance, will be examined as a case in point to illustrate many of the social dynamics that create and sustain inefficient systems. Soft systems methodology will be employed to compare the actual system with models of its parts (Checkland & Scholes, 1990). The paper will conclude with recommendations for the design of a more efficient system for paying the costs of health care.

HOW DID THE U. S. HEALTH CARE INSURANCE SYSTEM EVOLVE?

Early forms of health care insurance in the U.S. consisted primarily of private hospitalization insurance policies designed to cover catastrophic costs associated with severe illness. Some employers also undertook to provide health care facilities for employees and their families. Municipalities funded public hospitals for the poor and many private hospitals also accepted charity cases. Ordinary doctor bills and the costs of medicines were usually paid out of pocket or kept on account. This system was reasonably effective and efficient.

Employer-provided Group Health Insurance

The situation began to change in the 1940's when employers were looking for ways to attract and retain employees without running afoul of wartime wage controls. Offering health insurance as a benefit became an attractive option, especially after the Internal Revenue Service ruled in 1943 that employers' payments for group health insurance were not taxable as income for the employees (Arnett, 1999). These payments were also exempted from the employer’s and employee’s Social Security (FICA) tax as well as most state income taxes. Thus, federal and state tax preferences served as a substantial incentive for employers to assume the role of being the major provider of health insurance in the U. S. Labor unions, which were growing stronger during this period, jumped on the bandwagon and demanded better health care benefits. By 1979 more than half of the workforce, and more than four-fifths of the full-time employees, were covered by group health care plans provided by their employer (Chollet, 1984).

Large employers saw health care insurance as a relatively inexpensive benefit not only because of the tax exemption but also because their purchasing power enabled them to obtain group insurance at a discount from what individuals would have to pay for the same coverage. Thus, a benefit that would cost an employee $100 if purchased privately with after-tax dollars might be purchased at a net cost of $50 or less to the employer. Since this was true even of insurance that covered first-dollar costs, the policies that were written tended to be much more generous in their coverage than earlier policies had been. The advantages of tax-sheltered group coverage masked the extra costs involved in having every medical bill go through insurance processing. From the point of view of employees and labor unions employer-paid health insurance was a good deal because the employees received better insurance coverage and saved money on taxes.

The differential in favor of employer-paid insurance was moderated by the Social Security Amendments of 1965, which permitted an individual income tax deduction of half of the cost of private health insurance, up to $150. But the 1982 Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act (TEFRA) eliminated this personal deduction, thereby widening the disparity in favor of employer-provided group policies. By 1983 the value of federal tax exemptions of employer health insurance payments was estimated to be over $16 billion annually, compared to $4.2 billion for individual health care deductions (Chollet, 1984).

One result of the rapid expansion of employer-provided group health care insurance was an increase in utilization of health care services and a broadening of coverage. Since the direct cost to employees and their families of going to the doctor or the hospital was very small, they tended to go more often and for a wider variety of ailments. Employees also tended to think of health care insurance as a gift from their employer, although employers and labor unions were well aware that it was offset by lower wages (Arnett, 1999). Another result was that the cost of individually-purchased health care insurance policies escalated as preferred risks (prime-age working adults and their families) were absorbed into employer-provided group plans.

Employers and employees seemed at first to take little notice of inflation in health care costs, perhaps because they were not paying the full costs. By the late 1970s, however, there was growing concern that these costs were growing excessively. In 1960 only 5.3 percent of the gross national product (GNP) was devoted to health care, but that percentage doubled by 1983 and by 1993 it had risen to 14 percent (Stewart, 1995).

Employers, who tended to believe that the escalating costs of health benefits were coming out of profits, looked for ways to cut costs by decreasing coverage, not covering part-time

employees, and increasing deductibles and copayments. They also shopped for insurers who would charge less, and tended to offer little or no choice of policies to employees. Labor unions and economists tended to view the costs of benefits as coming out of the workers' pockets, with the employer simply acting as a tax-privileged purveyor (Pauly, 1997). Thus, unions argued for more choices and for wage increases to offset any reduction of health care benefits.

Meanwhile, concern grew for the uninsured and for small employers, who complained that they were unable to afford to provide health-care insurance for their employees. The policies that were available to small employers were much more expensive than those available to medium and large employers. Insurance for employees of small firms was more expensive because of adverse selection -- small employers were less selective in their hiring -- and greater marketing and administrative costs per employee.

Government-provided Health Care Insurance

The first tentative foray of the U. S. federal government into providing health care insurance to its citizens was the War Risk Insurance Act of 1917, which extended medical and hospital coverage to veterans. Shortly thereafter proposals were floated for universal federal coverage of catastrophic health care costs. However, the American Medical Association (AMA) and other forces were able to block proposals for federal health care insurance for the general populace until passage of the Social Security Amendments in 1965. These amendments provided hospital insurance (HI or Medicare Part A) for those covered by Social Security or Railroad Retirement, supplementary medical insurance (SMI or Medicare Part B) for anyone over sixty-five, and Medicaid for the indigent.

In 1972 Medicare coverage was extended to the disabled and, for a premium, to anyone over sixty-five not covered by Social Security. At the same time, however, in light of evidence that the costs of Medicare and Medicaid coverage were expanding faster than the medical care component of the Consumer Price Index, some limits were placed on costs and Professional Standards Review Organizations (PSROs) were established. PSROs were to monitor costs, degree of utilization, and quality of care for Medicare and Medicaid patients. The hope was that monitoring would encourage restraint in utilization and price increases.

Over the period 1966-1984 the annual compound rate of increase in Medicare insurance costs was over 16%. Even adjusted for inflation the increase was greater than 9% (Gornick et al., 1985). It was found that more than two-fifths of the increase was attributable to increased utilization of services (Virts & Wilson, 1983). One response to the increase in utilization was the National Health Planning and Resource Development Act of 1974, regulating the construction of new health care facilities on the basis of need.

Cost Containment

Economists recognized the inefficiency of the U. S. health care marketplace in the 1970s. Greenberg (1993, 362) notes that during the 1970s the system "was driven by cost-based reimbursement, state regulatory controls on hospital costs and prices, federal and state health planning and certificate-of-need laws, severe limitations on hospital privileges for nonphysician providers, and a complete absence of information about the quality of care and price of providers." In other words the system was very far from the competitive free market conditions that are supposed to produce market efficiency.

This situation began to change in the late 1970s with the growth of HMOs and preferred provider organizations (PPOs) which offered a competitive alternative to the traditional health care delivery system. The number of medium and large employers offering a choice of health plans also increased (Jensen, Morrisey, & Marcus, 1987). Health care professionals and organizations became subject to antitrust prosecution as a result of the Goldfarb v. Virginia State Bar decision of 1975. Most states dropped their regulatory programs and health-planning legislation.

In the 1980s federal efforts to reform the health care marketplace focused on cost containment. The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1981 limited reimbursements for many health care services under Medicare and reduced transfer payments to the states under Medicaid. It was assumed that the states would find ways to contain the escalating costs of Medicaid. The aforementioned TEFRA of 1982 set a flat payment per hospital patient and put a ceiling on increases in hospital revenue. These changes put hospitals in a straitjacket and generated intense lobbying for relief. The result was the Prospective Payment System (PPS) introduced by the Social Security Amendments of 1983.

The PPS linked the amount of Medicare reimbursement to the patient's diagnosis, adjusted by such factors as prevailing wage rates and hospital location. The PPS provided incentive for hospitals to cut costs. In response, they reduced the length of a patient's stay and shifted some procedures to outpatient status. But PPS did nothing to limit increases in the costs of Part B. These payments to physicians increased at a rate of over 17% per year from 1970 to 1983. The federal government briefly attempted to freeze the Medicare cap on physicians' charges, but succumbed to lobbying by physicians' groups. Yet the system of payments tended to distort patient care by favoring high-tech services over basic care and giving higher compensation to physicians in urban areas, thereby encouraging physicians to congregate there (Hamowy, 2000). These distortions were somewhat ameliorated by the Budget Reconciliation Act of 1989, which established a very complex system for determining payments. This new system appears to have moderated the increase in costs for physicians' services, yet those costs continue to increase rapidly.

DISTORTING THE SYSTEM

Prior to the 1940s the system of health care in the U. S. was characterized by relatively easy access for all but the poorest citizens, independent practice for physicians, personal

relationships between physicians and their patients, direct out-of-pocket payment of most medical bills, availability of reasonably-priced private hospitalization insurance plans for

those who desired such coverage, and charitable emergency care for those who were unable to pay. Inflation of medical costs was no steeper than for other goods and services. Although the picture was not perfect, it was better in many ways than the system we have now. What changed the system?

Tax Preferences

The tax preferences established in 1943 for employer-provided health care insurance are credited with fueling the explosive growth of third-party payment of medical bills in the U. S. (Arnett, 1999). Enrollment in employer group health insurance policies increased steadily from less than 10 million enrollees in 1940 to almost 160 million in 1970 (Helms, 1999). Today 60 percent of all Americans obtain their health insurance through their own or a family member’s employment. Increasing reliance on private health insurance is further demonstrated by the fact that premiums for health insurance (both employer- and individual-paid) rose from $10 billion in 1965 to $296 billion in 1993 (Helms, 1999).

The tax preference given to employer-paid health care insurance turns out to be highly regressive. The exclusion of such insurance payments from income is worth more to employees in the higher tax brackets, such as executives. Steuerle and Mermin (1999) estimate that the exemption is worth $634 per capita for families whose income is in the highest 20 percent but only $49 per capita for families in the lowest 20 percent. Low-income families may be covered by Medicaid, however. It is the families in the middle of the income distribution who are hit hardest, since they receive little benefit from the tax exemption. If they work for small employers, as is often the case, they may also have to buy their own health insurance at much higher rates than those paid by large employers.

One direct result of the explosive growth in private health insurance is that third-party payment of insurance claims, which accounted for less than five percent of payments for medical care in 1948, now represents the great bulk of payments to health care providers today. Even those claims that are ultimately paid by the consumer, because the claim is denied or the annual minimum has not been reached, go through insurance processing by both the insurer and the provider. According to Stewart (1995) the increased costs of medical care can be attributed primarily to the growth of third-party payments, which affects all the other causes of increased costs, even the aging of our population. Increased private insurance coverage plus Medicare and Medicaid have stimulated the increases in excess demand, fees and prices, salaries and earnings of health care professionals, oversupply of medical services, overutilization of facilities and equipment, and spending on medical research. Technological improvements are the other major factor.

Another result of reliance on employer-provided health care insurance is that most employees think it is free. They assume their employer is paying for the insurance on top of what would be paid in wages anyway. Economists, as well as many business executives and labor leaders, know this is not true. Benefits are provided in lieu of wages. But the tax preference for employer-paid health insurance allows the employer to give employees more for their dollar. Thinking that the benefit is free, however, employees are then inclined to consume more of it. Economists call this the moral hazard of seemingly free goods, the tendency to consume more than one needs. Over-consumption drives up the cost of the good, both directly and indirectly. The direct increase in the cost of insurance comes when insurers increase premiums to pass on the costs of increased claims. The indirect effect comes from increased demand on a relatively fixed supply of health services, causing prices to increase. Providers may also succumb to moral hazard in the form of increasing prices more than justified by demand, because the bill is being paid with little resistance. Whenever consumers are unaware of the true cost of their consumption, inefficiency is introduced into the marketplace (Vogel & Blair, 1975).

Administrative Costs

One of the results of paying most medical costs through insurance or managed care, rather than through direct payment from patient to provider, is an increase in administrative costs. Woolhandler and Himmelstein (1991) estimate that in 1987 overhead and billing expenses incurred by physicians’ offices and insurers accounted for 25-48 percent of all expenditures on physicians' services in the U. S. In other words, at least a quarter and perhaps almost half of all the money spent on physicians' services was paid for administration, not for medical care.

For that same year overhead for private insurers was estimated at 10.5 percent of premiums or 11.7 percent of benefit payments (Danzon, 1993). Overhead includes underwriting expense, claims administration, marketing, premium taxes, return on capital, and investment income. Although Danzon argues that some of these costs do not represent waste, the fact is that the costs would not exist if medical bills were paid directly by patients. In a government-run health care system there would still be a need for claims administration or something similar, but Danzon (1993) estimates that claims administration by insurers amounts to only 3-4 percent of benefit payments.

Systemic Response to Stimuli

The picture that emerges from this brief history of private and governmental health care insurance in the U. S. is that there are complex feedback effects between insurance and the costs and utilization of health care services. When the costs of health care services are lowered for portions of the population, either through tax preferences or by a government insurance program, the utilization of services and the costs of those services increase rapidly. Indeed, costs increase more rapidly than general inflation (Chollet, 1984).

It appears that the lowered costs to certain consumers invite a "feeding frenzy," while the existence of "deep pockets" to pay the bill encourages price gouging by providers. When

the government and the insurance companies (or their clients, the employers) react by putting caps on payments, adding copayments, and reducing coverage, consumers react by looking for someone else to pay. Hospitals cut costs by such methods as reducing length of stay, moving some services to outpatient status, and expanding the workload or freezing the pay of staff. When hospitals and physicians cannot increase prices for insured patients because of caps imposed by Medicare or the insurance companies, they shift the costs onto their uninsured patients. Some hospitals are forced out of business.

The formation of HMOs and PPOs is encouraged by insurers and employers as a means of reducing costs. Many physicians who might prefer to be independent, and many patients who might prefer a personal physician, are forced to join HMOs or PPOs. Thus, employer-paid insurance creates problems for both patients and providers. Insurers seek to avoid or dump non-preferred risks (e.g., smokers, homosexuals, people with prior illnesses, older people), who of course are in the greatest need of insurance. Meanwhile, both private and government insurance programs continue to process virtually every medical bill incurred by their clients, whether it is eligible for payment, applies to the deductible, or is submitted in error.

Large employers operating in multiple sites are confronted with a difficult and costly management problem, because they may must contract for services with dozens, even hundreds, of providers (Chollet, 1984) and may offer multiple policy options (Luft, 1993). Small employers, who present a greater risk and a smaller market to insurers, are faced with rapidly rising costs of insurance that cause them to reduce benefits or eliminate the health care benefit entirely (McLaughlin, 1993). This increases the percentage of the population having little or no health care insurance.

At the current time there are approximately 40 million Americans without health insurance. Meanwhile, sources of free or subsidized health care are drying up. Hospitals used to underwrite health care for the indigent and uninsured by shifting costs to the insured patients. Faced with intense pressure from insurers and the government to cut costs, and forced to agree to fixed price schedules for services, hospitals can no longer shift costs. Instead they reduce hospital stays and deny services to the uninsured (Reagan, 1992). There is also massive consolidation among hospitals, with many being purchased by HMOs, which means that alternative sources of care have been drying up.

We are left with a system that keeps escalating in cost in spite of (and to some extent because of) intense efforts to contain those costs. For instance, although many insurers

use some form of utilization review (UR) to guard against paying for unnecessary or inappropriate medical care, no one really knows whether the benefits of UR outweigh its costs (Dranove, 1993). A select group of people employed by large employers, as well as the aged, disabled, and indigent, receive as much care as they want at managed prices and little cost to themselves, while a large and growing group are uninsured and can receive care only if they are able to pay the full, inflated cost themselves. The care everyone receives is more high-tech but less personal and less convenient. Physicians find it difficult to operate independently and must wait for payment. Hospitals are forced to reduce services, cut staff, freeze wages, merge, join HMOs, or go out of business.

How did we get in this mess? For our health care insurance system is truly a mess in the sense defined by Ackoff (1974, 21): "a system of external conditions that produces dissatisfaction." History seems to indicate that creation of tax incentives for business firms to provide group health care insurance for their employees and families was a major

contributor. It generated a system of private health care insurance that provided "generous" benefits for a privileged class, which in turn encouraged inflation and overutilization, which created problems for other consumers and for health care providers. Even before that, however, there were several failed attempts to pass federal legislation providing for some sort of universal health care insurance. If that legislation had passed, the "privileged class" part of the problem would have been avoided, although the effects of increased utilization and escalating costs would still have been with us. Instead of our current mess we might have had one similar to Great Britain's.

We cannot overlook the role of changing technology. New procedures, new machines, and new medicines were being developed rapidly throughout the period we have been examining. These new developments added to the cost of health care in various ways: many of the new machines and medicines were expensive to develop and manufacture, and some of the new procedures required expensive technology, were time consuming, or led to extended hospitalization (Reagan, 1992). The system of payments did not encourage researchers to search for cheaper alternatives to existing medicines, machines, or procedures.

The average life span increased rapidly during this period, as did the over-65 population. This accounted for some increased utilization and pushed the costs of Medicare far beyond what was anticipated when the program was created. This in turn led to cost containment measures by the federal government which were emulated by private insurers.

One of the hallmarks of a system in disarray is a never-ending series of attempts to "adjust" or "fix" the system. Monheit (1999, 99-100) notes that:

A variety of proposals and legislative interventions have sought to address...deficiencies in the employment-based insurance system. Beginning in the early 1980s and continuing through the mid-1990s, a number of initiatives were aimed at providing health insurance to unemployed workers, mandating coverage to working families (both prior to and as part of the proposed Health Security Act of 1993), ensuring the continuity of coverage for insured workers who either change jobs or lose employment -- through the 1985 Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (COBRA), state portability mandates, and the 1996 Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) -- and altering the tax treatment of employment-based coverage and expanding tax-deductibility for self-employed owner-operators of unincorporated businesses (through the Tax Reform Act of 1986 and the 1996 HIPAA, respectively). In addition, small-group health insurance reform, implemented by many states during the early 1990s, sought to expand access to coverage by small employers through guaranteed issue and renewal of policies, limiting the exclusion of preexisting conditions, ensuring portability, and constraining premium levels and their rates of growth.

The history of the health care insurance system in the U. S. contains many examples of attempted "fixes" that created new problems. Tax incentives for employers to provide health care insurance to employees, as well as the Medicare and Medicaid programs, were attempts to protect the health of citizens in lieu of a universal insurance system which Congress could not pass. Employer-provided health care insurance generated a new bureaucracy to process claims, while generous coverage meant that almost every medical (and often dental and vision) procedure created a claim. Medicare and Medicaid also expanded the federal bureaucracy. Each of these bureaucracies not only produced new costs in themselves, but also caused hospitals and physicians' offices to increase their staffs to handle the paperwork. Physicians who had operated independently were impelled to band together in order to share the costs of insurance processing. One of the attractions of HMOs and group practices was that these costs could be pooled.

Increasing costs fueled in part by the insurance "fix," but also by new technology and an aging population, called for federal regulations and moves by insurers to try to contain those costs. Cost-containment had a variety of unintended effects: many hospitals were closed, HMOs refused treatment that would otherwise have been provided, hospitals and physicians made up for lower prices allowed by Medicare or an insurer by charging higher prices to the uninsured, insurers refused to cover expensive procedures and drugs, many high-risk patients could not find insurance at any price, pharmaceutical firms began to advertise on television in order to encourage patients to ask their doctors for expensive drugs, and elaborate new cost-containment formulae required expansion of the bureaucracy to administer them.

Despite these problems health care is probably much better in many respects than it was fifty years ago. New technology is the primary source of improvement, but it must also be said that the system has been able to fund the development and deployment of that technology. Cost-containment has not stifled creativity; but it has also not fully contained costs. Both cost containment and the various insurance programs have escalated costs by generating new bureaucracies to administer them. Claim processing not only adds costs to the system, it also slows the process of payment. This forces providers to find additional financing to cover the "float" in the system of payment, adding interest costs or fund-raising costs to the system.

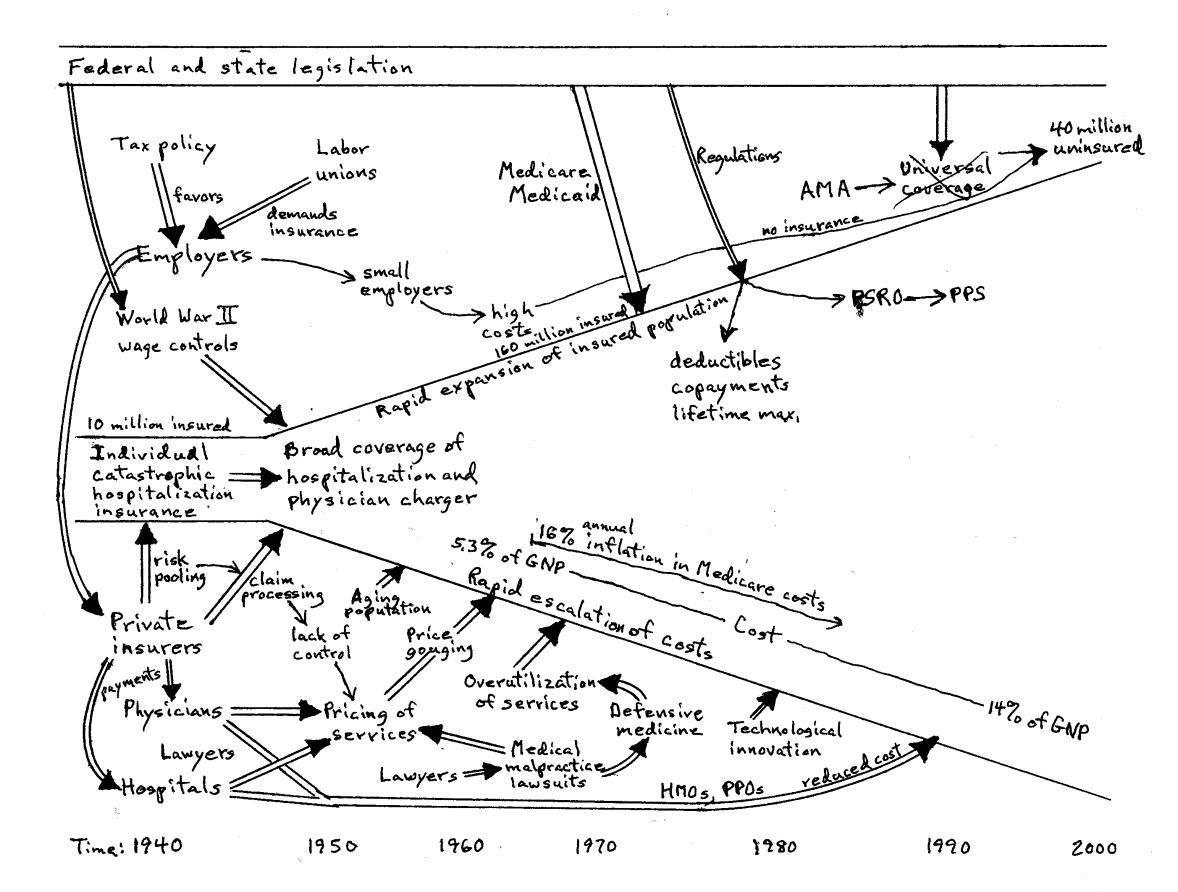

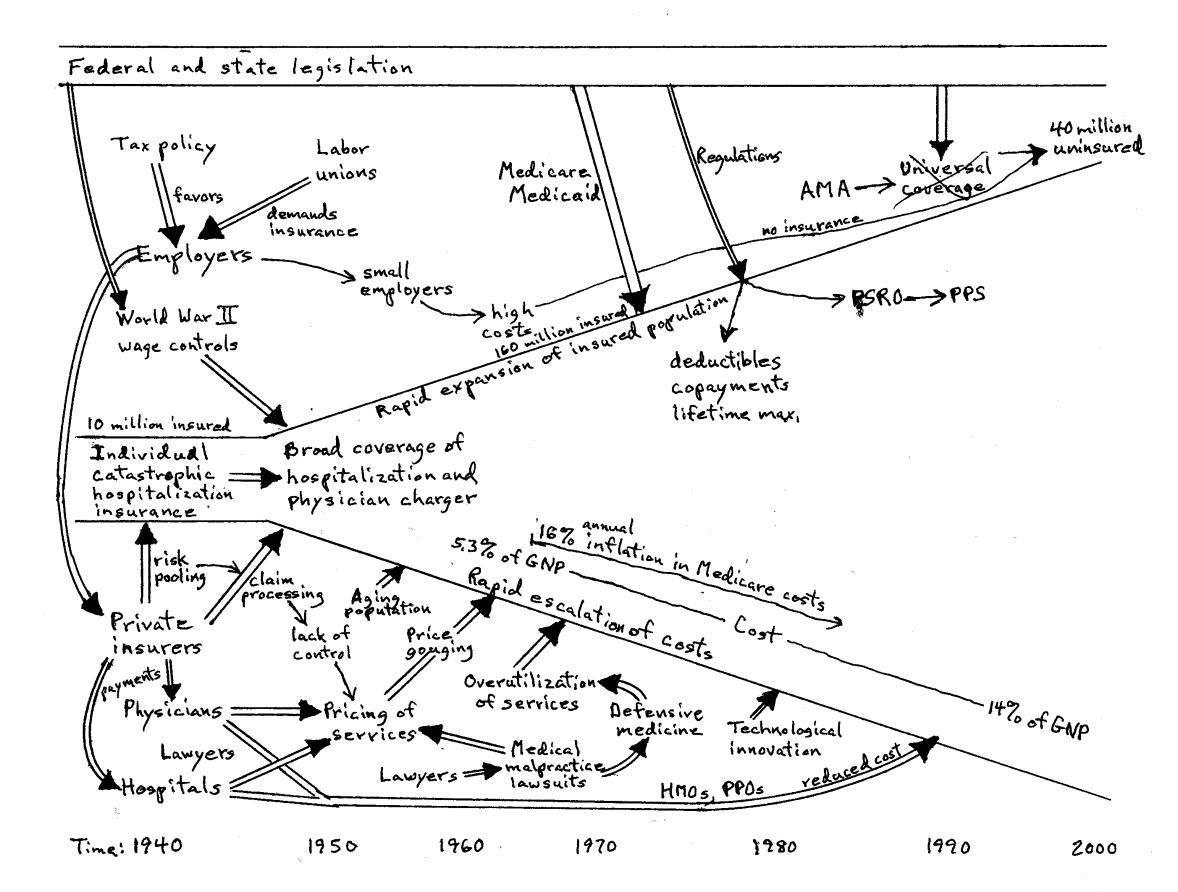

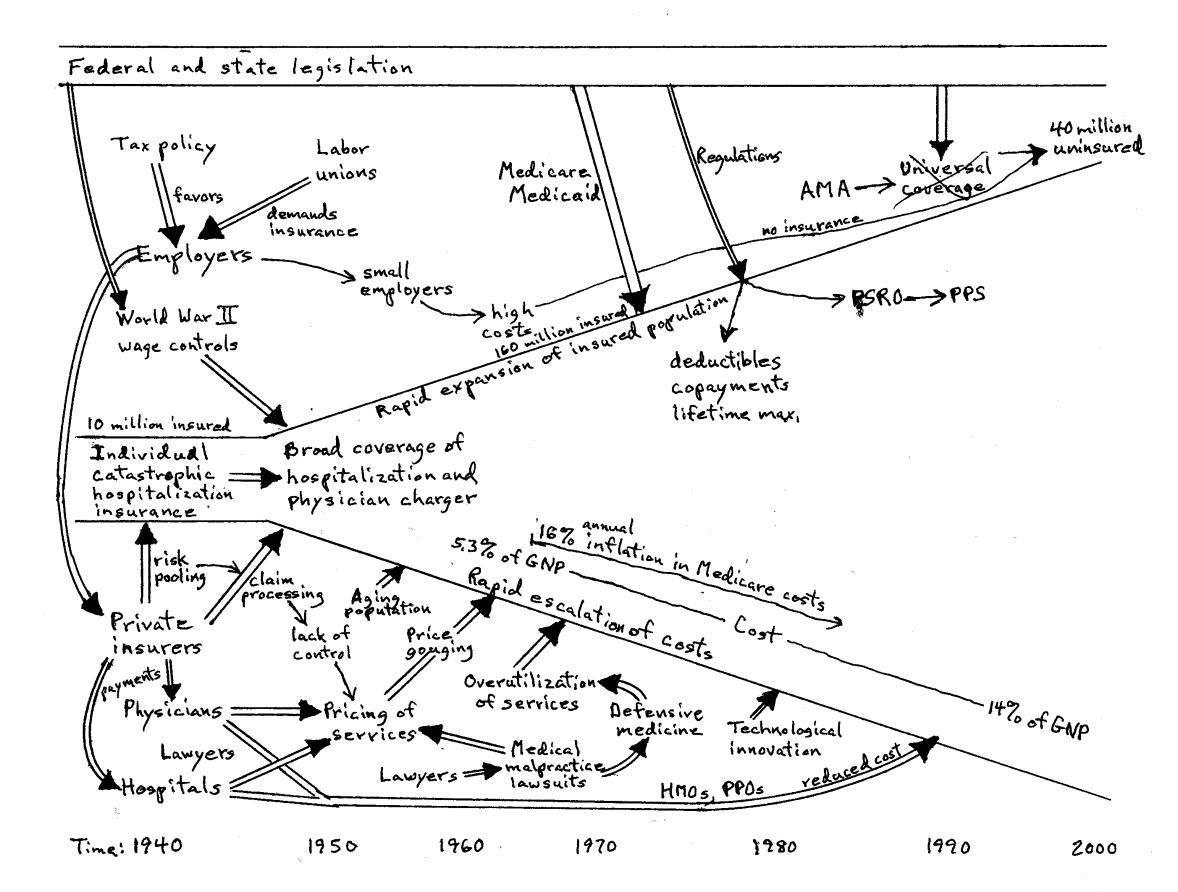

Figure 1 attempts to provide a "rich picture" of the situation that I have just described. It encompasses the major players in the system: Employers, labor unions, insurers, physicians, hospitals, the federal government, the AMA, and programs such as Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, and PPS. The flow of money is represented by broad arrows; other influences causing change in the system are shown as thin arrows.

Figure 1. Rich Picture of Evolution of U. S. Health Insurance System

A NEW MODEL

There have been numerous proposals to reform the system of health care insurance in the U. S. The proposals tend to run in opposite directions. On the one hand are plans for national or universal health insurance, such as those proposed by the Clinton administration in 1993, whereby either the federal government or the private insurance industry would undertake to insure all citizens. On the other hand are proposals to remove tax incentives and allow the free market to operate (Pauly, 1997; Arnett, 1999). Between these poles Congress continues to tinker with the existing system, for instance by supporting regulations and encouraging the states to provide insurance for children through the State Children's Health Program, enacted in 1997.

Criteria

Few of the proposals for reform of the health care insurance system are directly concerned with the efficiency of that system. Efficiency is a primary criterion in the development of the model to be presented here. An inefficient system sustains itself only at great cost to other systems.

Stability of the system is also a concern, because an unstable system requires continual tinkering and application of energy to keep it in order. Thus, equity is important because inequity tends to be an unstable condition. Equity implies that there should be universal access to basic health care coverage, unlike the current system, which favors those who are employed. Finally, since the purpose of health care insurance from the consumer's point of view is to assure access to medical care when it is needed, the system should promote the maintenance and improvement of health care services (Committee, 1993). It should not discourage innovation or curtail the deployment of new technology.

Initially political realities will be ignored. Ultimately, however, politics is part of the system. We will have to consider whether it is politically feasible to move in the direction of the model. It will help if the model appears to meet the needs of a wide variety of constituents.

An Ideal System?

What would a streamlined, efficient system look like? Two different models seem to offer promise. One is a prepaid medical care system, such as that offered by HMOs and PPOs, with copayments and deductibles. The alternative is a catastrophic insurance system that treats everyone equally. It is also possible for these two systems to coexist.

Although HMOs have come under a lot of criticism for providing cold, machine-like service and emphasizing cost over professional judgment in deciding what care will be provided, they are relatively efficient. PPOs are more user-friendly, but perhaps less efficient. An adequate level of competition among HMOs and PPOs would serve to moderate the negative aspects of both or permit consumers to choose between low cost and supportive service. Currently such competition exists only in large urban areas.

A catastrophic health care insurance system would also be efficient. It would not attempt to provide comprehensive insurance coverage, except perhaps for the indigent. Covering even routine costs and including them in the claim-processing procedure adds a large amount of inefficiency to the system, as well as causing people to act as if health care had no cost. Thus, citizens should be expected to budget for routine, expected health care costs and to pay them directly out of pocket. Only when the costs are unexpected and large enough to cause financial distress should an insurance claim be made. The aim of insurance should be to protect citizens from unexpected costs that could exceed their ability to pay. From the point of view of public policy the intent is to remove cost from the equation that determines whether a person will receive appropriate medical treatment, without otherwise distorting the system.

Removing cost as a factor immediately invokes the likelihood of increased utilization and price escalation, especially for the more costly services. Increased utilization may not be

entirely a bad consequence -- more frequent visits to the doctor may reveal serious illness earlier in its development, when treatment is less expensive and more likely to succeed.

Excessive utilization of health care services can be curbed through copayments and deductibles, so that the services are not perceived as free (Manning et al., 1987). This will not deter everyone; hypochondriacs will still be hypochondriacs and physicians will still be motivated to prescribe unnecessary procedures. Yet this would be true even without insurance. What should be kept in mind is that the anticipated copayments must be factored into estimates of what costs each person can be expected to pay out of their pockets before the insurance kicks in.

If price escalation is deemed a serious problem, the solution does not lie in creating a costly bureaucracy to contain it. Rather, competition should be encouraged within the system and information should be provided that allows the consumer to make an informed decision. A moderate amount of competition among providers for the business of well-informed consumers provides a low-cost mechanism for regulating prices, whereas regulation is a high-cost (and often ineffective) mechanism.

Regardless of which model system is chosen it would have to be freed from the tyranny of price regulation and tax preferences. Price regulation creates rigidities that interfere with the efficient operation of a competitive market. Tax preferences create inequalities in the treatment of consumers and destroy the balance of competition. I will later address the question of how to rid the system of these distorting factors.

The cost crunch comes in both model systems when new technology makes it possible to sustain life almost indefinitely. If the costs to the patient do not determine a cutoff point, there must be some other mechanism to indicate when the cost is too steep. One mechanism that is already in place, the lifetime maximum insurance benefit, does seem to offer a partial solution. The system could authorize that, when that amount is used up, the machines will be turned off. There would have to be some mechanism for appeal and exceptions, however. After a million dollars has been spent, it would not make sense to suspend treatment when a few thousand dollars more would be likely to bring a cure. An experimental treatment that would run over the limit might be authorized because of its potential future value. Again, a bureaucracy to administer rules about appeals and exceptions is not the answer. Ad hoc juries of doctors, representatives of the insuring agency, and members of the public would fit our democratic ideals. Such juries could be convened to rule on exceptions.

One of the factors pushing physicians to order unnecessary tests is our current penchant for medical malpractice suits. These suits also force physicians and other providers to carry very expensive malpractice insurance, which drives up the costs of medical care for everyone. The AMA estimated in 1991 that defensive medicine added about $15 billion annually to the cost of health care and that malpractice insurance premiums added $5.6 billion (Reagan, 1992). The topic of malpractice insurance is outside the scope of this paper, but ultimately might have to be considered in a thorough reworking of the system.

How to Get There

First it should be recognized that there is a third part of the health care insurance system, the publicly-financed part, that is not going to go away. Congress would not dare to

eliminate Medicare, Medicaid or other public health care programs, no matter how efficient and effective the private sector might become. These programs have become entitlements for various segments of the population. Since these programs, with the exception of veterans’ benefits and military medical care, generally work in conjunction with the private sector, improvements in that sector will also benefit the public programs.

In trying to develop an equitable and efficient private system of health care insurance, the danger posed by the continuing existence of a public system is that it will lead to regulation that interferes with the efficient operation of the market. That is what happened when costs began to spiral out of control in the 1970s. Thus, one requirement for moving toward our model system is that the federal and state governments will forego regulation of that system. The chances of that happening are better if the model system can be shown to reduce costs and provide coverage for everyone not covered by the public system.

For the private system there seems to be no reason to choose between a system based on catastrophic insurance or prepayment for health care with copayments and deductibles. The two models do not conflict; indeed, they provide competition for each other and provide consumers with a choice. Furthermore, the public system is used to working with both of the private models.

The greatest impediment to moving toward a system based on insurance only for catastrophic health care costs is the public perception that health care should be free. Thus, it would not be a popular move for Congress to alter Medicare, Medicaid, and other federal programs to require substantial copayments and high annual deductibles. Nor would union members be happy if their leaders negotiated to reduce the insurance package from full coverage to catastrophic costs only. Yet these changes might be palatable if they were combined with benefits. For instance, requiring Medicare recipients to pay the first $X of annual costs could be coupled with addition of prescription coverage (also after an annual minimum). If the tax code were amended to permit employers to deduct insurance expenses only for catastrophic health care insurance (suitably defined) or prepaid care with copayments and deductibles, unions could demand that the difference be added to wages so that employees would be able to pay the deductible.

If our public policy is to ensure a healthy populace by ensuring that everyone can receive adequate health care, there is no reason to continue to tie health insurance to employment.

Providing insurance through the employment relationships obscures the true costs of the system and promotes overuse. The tax advantage for employer-provided health insurance should be repealed. Large employers would still hold a competitive advantage over small employers and individual consumers because of lower costs of marketing and administration of the insurance. They need no further assistance.

The distortions of the market caused by the tax preference for employer-paid health insurance have been recognized for decades. Proposals have been made to eliminate the tax preference, but they have died without a vote in Congress. What sort of change in the tax code might be palatable to our lawmakers and assorted lobbyists? One possibility is to amend rather than eliminate the tax preference so that it applies only to catastrophic health care insurance and/or prepaid health care. This change would at least reduce the distortions caused by first-dollar coverage.

Another possibility is to effectively give the same tax preference to everyone, whether or not they receive their health insurance through their employer. This could be done by allowing full income tax deductibility for all health insurance premiums, even for those who take the standard deduction. This would remove some of the inequity in the current system, although overutilization would still be encouraged.

A third alternative is to expand the use of medical spending accounts (MSAs). Because people with MSAs are spending their own money for health care, this proposal would tend to increase cost-consciousness and thereby aid cost containment (Jensen, 2000). Yet the money in MSAs is tax exempt, so MSAs compete favorably with other tax-favored solutions.

The question of selection in the pool of health care consumers is a difficult one. The public interest might suggest a policy in which insurers are required to accept everyone into a single pool and charge a uniform price so that no one is excluded from coverage. This policy would ease the growing concern over use of genetic testing results to deny coverage. Granted, the policy limits the right of healthy people to sell themselves as desirable customers and protects undesirable behavior such as smoking, but it promotes national unity. If private insurers fight this provision, then the threat of universal national health insurance might be invoked.

Yet preventing insurers from exercising reasonable prudence in choosing whom they will insure or what price they will charge interferes with the free competitive market and introduces inefficiencies. Intense competition for the low-risk, low-cost pools represented by large employers will skew the market and encourage under-the-counter deals. Insurance companies that fail to balance high-risk enrollees with those of lower risk will have to charge a higher, uncompetitive price or lose profitability. Either way they will eventually be forced out of the business, thereby reducing competition.

There are several ways out of this dilemma. One is to allow a free market to reign, with the government acting as the default insurer for people who are unable to obtain insurance in the private sector. Another is to require that insurers accept everyone but allow a stratified price and/or benefit schedule based on risk. The principle would be that insurance should cover unexpected catastrophic health care expenses. A person who has cancer would be a poor risk for insurance that covers the costs of cancer treatments but might be a good risk for coverage of other conditions. Thus, insurers could exclude preexisting conditions, with the government again acting as the insurer of last resort for those conditions, but issue a policy at reasonable cost for all other unexpected catastrophic costs (Epstein, 2000). In fact, a free market would allow insurers to write and consumers to select policies that cover only specific risks.

Figure 2 presents a picture of a health care insurance system that would be more efficient and would contain fewer distortions of outcomes than does the current system. Note that this system is quite a bit simpler. The incrustations of bureaucratic subsystems designed to correct distortions have been removed. The model presented in Figure 2 attempts to rely more on proper initial design and corrective feedback provided by a free market. The system is not intended to be perfect, whatever that might mean. It is a compromise based on political realities and, of course, it is an open system that is susceptible to new distortions. As I indicated above, for instance, the advance of medical technology may cause many people to reach their lifetime maximum and make it necessary to introduce mechanisms to adjudicate reasonable exceptions.

Figure 2. Model of Fair and Efficient System.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

We have examined an existing social system, the health care insurance community in the U. S., employing a combination of living systems theory (LST) and soft systems methodology (SSM). With SSM we developed a rich picture of the interactions occurring in the system. The principles of efficiency and equity were then employed to develop models of a more viable and effective system. Finally, we considered what adjustments might be feasible to move the system from its present state to a more efficient and equitable state.

The health care insurance system in the U. S. was once reasonably efficient, ruled by market force and prudent insurance principles. It adjusted to changes in the tax code, expanded rapidly, and moved in the direction of being primarily a processor of claims and payments for health care, rather than a pooler of risk. Costs escalated rapidly because of increased administrative expenses, overutilization of services, unchecked provider greed, an aging population, and technological innovation, as well as increased litigiousness. The government responded by further restricting the free market with regulations and by entering the market to provide coverage for select groups. The structure of the health care provider system was pushed in the direction of centralization of services in hospitals and group practices, as well as toward prepaid health care in the form of HMOs and PPOs.

These changes left everyone dissatisfied. Consumers grumbled about high costs, poor service, long waits, loss of personal relationship with a physician, and (in some cases) inability to find affordable insurance. Employers worried about loss of profits because of escalating costs. Large employers had to deal with a plethora of providers and insurers; small employers often found they could not afford to provide insurance to their employees. Physicians complained about loss of independence, assembly-line medicine, slow payment of bills, and malpractice lawsuits and insurance costs. Hospitals and other provider organizations suffered from suffocating regulation, increased paperwork, slow payment of bills, and being squeezed by cost containment measures. Federal and state government became alarmed by rapidly escalating costs of health care, a large body of uninsured citizens, overutilization of services, and inequities in the health care insurance market. Private insurance companies profited from a greatly enlarged market and less risk, but complained of subsidized competition from Blue Cross/Blue Shield and government insurance programs as well as increased exposure to lawsuits and regulation. If satisfaction of the constituents is a measure of the health of a living system, the health care insurance community in the U. S. is in dire straits.

It took only small perturbations of the system to move it from its former state to its present state. The change is irreversible, however. We cannot simply return to the original state by removing tax preferences, dropping price controls, canceling regulations, and eliminating government health insurance programs, even if that were politically feasible. What we can do is look for small changes, small enough to be politically acceptable, that will nudge the system back in the direction of efficiency and equity. Those are the sorts of changes I have proposed here.

REFERENCES

Ackoff, R. (1974). Redesigning the Future: A Systems Approach to Societal Problems. Wiley, New York.

Arnett, G. (1999). "Introduction and Overview," in Empowering Health Care Consumers through Tax Reform, (G. Arnett, ed.), The University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor.

Checkland, P., and Scholes, J. (1990). Soft Systems Methodology in Action. Wiley, New York.

Chollet, D. (1984). Employer-provided Health Benefits: Coverage, Provisions, and Policy Issues, Employee Benefit Research Institute, Washington.

Committee on Assessing Health Care Reform Proposals. (1993). Assessing Health Care Reform, National Academy Press, Washington.

Danzon, P. (1993). "The Hidden Costs of Budget-constrained Health Insurance Systems," in American Health Policy: Critical Issues for Reform, (R. Helms, ed.), AEI Press, Washington.

Dranove, D. (1993). "The Five W's of Utilization Review," in American Health Policy: Critical Issues for Reform, (R. Helms, ed.), AEI Press, Washington.

Epstein, R. (2000). "The Antidiscrimination Principle in Health Care: Community Rating and Preexisting Conditions," in American Health Care: Government, Market Processes, and the Public Interest, (R. Feldman, ed.), Transaction Publishers, New Brunswick.

Gornick, M., Greenberg, J., Eggers, P., et al. (1985). "Twenty Years of Medicare and Medicaid: Covered Populations, Use of Benefits, and Program Expenditures," Health Care Financing Review, Annual Supplements, 43.

Greenberg, W. (1993). "Elimination of Employer-based Health Insurance," in American Health Policy: Critical Issues for Reform, (R. Helms, ed.), AEI Press, Washington.

Hamowy, R. (2000). "The Genesis and Development of Medicare," in American Health Care: Government, Market Processes, and the Public Interest, (R. Feldman, ed.), Transaction Publishers, New Brunswick.

Helms, R. (1999). "The Tax Treatment of Health Insurance: Early History and Evidence, 1940-1970," in Empowering Health Care Consumers through Tax Reform, (G. Arnett, ed.), The University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor.

Jensen, G. (2000). "Making Room for Medical Savings Accounts in the U. S. Health Care System," in American Health Care: Government, Market Processes, and the Public Interest, (R. Feldman, ed.), Transaction Publishers, New Brunswick.

Jensen, G., Morrisey, M., and Marcus, J. (1987). "Cost Sharing and the Changing Pattern of Employer-sponsored Health Benefits," Millbank Quarterly, 65:521-50.

Luft, H. (1993). "Problems and Prospects in Multiple-Option Health Plan Settings," in American Health Policy: Critical Issues for Reform, (R. Helms, ed.), AEI Press, Washington.

Manning, W., Newhouse, J., Duan, N., Keeler, E., and Leibowitz, A. (1987). "Health Insurance and the Demand for Medical Care: Evidence from a Randomized Experiment," The American Economic Review, 77(3):251-277.

McLaughlin, C. (1993). "The Dilemma of Affordability -- Health Insurance for Small Businesses," in American Health Policy: Critical Issues for Reform, (R. Helms, ed.), AEI Press, Washington.

Miller, J. (1978). Living Systems, McGraw-Hill, New York.

Monheit, A. (1999). "Health Insurance, Employment, and the Labor Market," in Informing American Health Care Policy, (A. Monheit, R. Wilson, & R. Arnett, eds.), Jossey-Bass, San Francisco.

Reagan, M. (1992). Curing the Crisis: Options for America's Health Care. Westview Press, Boulder.

Steuerle, C., and Mermin, G. (1999). "A Better Subsidy for Health Insurance," in Empowering Health Care Consumers through Tax Reform, (G. Arnett, ed.), The University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor.

Stewart, C. (1995). Healthy, Wealthy, or Wise? M. E. Sharpe, Armonk, NY.

Virts, J., and Wilson, G. (1983). "Inflation and the Behavior of Sectoral Prices," Business Economics, 18:3,45-54.

Vogel, R., and Blair, R. (1975). Health Insurance Administrative Costs, U. S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Washington.

Woolhandler, S., and Himmelstein, D. (1991). "The Deteriorating Administrative Efficiency of the U. S. Health Care System," New England Journal of Medicine, 324:1253-58.