Back • Return Home

Conflict and Cooperation in Exchange between Living Systems

Lane Tracy

Department of Management Systems

College of Business Administration

Ohio University

(614) 593-2006

Conflict is usually treated as a phenomenon occurring at a specific system level. Thus, we have studies of interpersonal conflict, intergroup conflict, interdepartmental conflict, interorganizational conflict, and international conflict. Occasionally, there is discussion of conflict between levels, such as between an individual and an organization, but this is often reduced to a case of interpersonal conflict by focussing on a manager as the representative of the organization.

Living systems theory (Miller 1978) considers people, groups, organizations, and nations to be distinct levels of living systems, all possessing certain general characteristics of "life." A living systems approach to conflict permits development of a generic view of conflict as a facet of interaction between systems. This approach possesses the advantages of (1) enabling comparison of the views of conflict at the various specific levels and (2) facilitating the study of interlevel conflict, as between an individual and an organization.

Sources of Conflict and Cooperation

The basic sources of conflict, and of cooperation as well, lie in the characteristics of living systems. It is beyond the purview of a paper such as this to attempt to enumerate all of the general characteristics of living systems. With respect to conflict and cooperation, however, the important characteristics are as follows:

1. Living systems are open systems interacting with the environment, including other living systems, in order to maintain steady states of negentropy (Miller 1978: 18).

2. The behavior of living systems is purposeful, aiming toward maintenance of the existing system, actualization of its potential through growth and elaboration, and propagation of the system through replication and/or dissemination (Tracy 1986: 211-12).

3. Living systems require inputs of matter-energy and information to fulfill needs created by consumption, obsolescence and output of resources; they also must rid themselves of excess products and wastes.

4. Every living system possesses a decider subsystem which is responsible for setting and adjusting values, purposes and goals; analyzing data; synthesizing and choosing plans of action; and implementing those plans by issuing orders to other subsystems (Miller 1978: 68).

5. Living systems can exist only within narrowly limited environmental conditions; they may act upon the environment (again including other living systems) in order to maintain or improve those conditions.

In addition to these general characteristics, all living systems at the level of groups and above must share components of their decider subsystems. That is, they depend on individuals separately and collectively to make decisions for the system, but these individuals must also act as their own deciders and often as components of the deciders of other social systems as well (Tracy 1983: 570).

These characteristics of living systems establish the basis for conflict by determining conditions under which such systems may oppose each other. Five resulting conditions of conflict or opposition may be described as follows:

Resource conflict. Individuals, groups, organizations and nations all require inputs and outputs of resources. When they covet the same resources and those resources are insufficient to meet all needs, a condition of conflict exists.

Environmental conflict. Individuals, groups, organizations and nations require certain environmental conditions and they act to obtain or maintain those conditions. When they require different conditions within the same environment, there is a condition of conflict.

Member conflict. Groups, organizations and nations lay claim to the loyalty of individuals as members, and particularly as deciders for the system. Individuals must also be loyal to their own purposes. When two or more systems require such loyalty simultaneously but the values, purposes and goals of each system call for different decisions or behavior, a condition of conflict exists.

Role conflict. Individuals play many roles as members or components of groups, organizations and nations. When these roles make incompatible demands on an individuals or demands of a single role are incompatible, a condition of conflict exists.

Value conflict. Individuals, groups, organizations and nations seek to propagate their values to other systems. When the propagated values are incompatible with each other or with existing values of the receiving system, a condition of conflict exists.

The last three forms of conflict fall within Miller's (1978: 39) definition of the term. That is, they are strains created by incompatible demands on a system. The first two forms are strains engendered jointly in two or more systems by incompatibility of each system's own purposes and goals with those of other systems.

The behavior of living systems is motivated to reduce such strains. This may be done cooperatively, i.e. in a manner designed to reduce strain in all of the interacting systems, or competitively. The resulting behavior is usually classified, respectively, as cooperation and overt conflict.

There are other sources of conflict inherent in the listed characteristics of living systems. For instance, within a system strain may be generated by conflicting demands of maintenance and actualization. For the purposes of this paper, however, it will be sufficient to focus on conflict between systems over resources and environmental conditions. These two forms of conflict involve exchange between systems. The intrasystem strains generated by conflict over members, roles and values will be the topic of a related paper.

Conflict or Cooperation?

Opposition involves values. Resource conflict occurs when two systems set equal value on a resource that is insufficient to satisfy both of them. The systems oppose each other over possession of the resource. Environmental conflict occurs when the purpose values of two systems call for different, incompatible conditions within the same environment.

A condition of conflict or opposition with another system over resources or environmental conditions will not necessarily result in overt conflict behavior. The energy and other resources required for an overt clash may tip the balance in favor of doing nothing. Another alternative is simply to withdraw from the situation. It may be easier to fulfill needs by moving to another niche or forming a cooperative relationship with another system, rather than competing in the current environment. Finally, incompatible purposes or demands can often be resolved in a mutually satisfactory manner through compromise or cooperation.

Despite the potential for conflict of purposes, the essence of living systems is cooperation. A large accumulation of cells must work together in order to form a living organ. Many organs must cooperate to keep an organism going. Groups and organizations require the cooperation of members in order to function. Individual members must cooperate not only with the suprasystem (i.e., any system of which they are members or components) but also with each other. The subsystems and components of any living system must accept the coordination provided by the decider, or else the system is crippled and may cease to exist.

Difference in values may set up an opportunity for cooperation. When systems value resources differently, a mutually satisfactory exchange is possible. For example, a person can exchange excess time, energy, and skills for an organization's excess money or goods. Each system's excess resources have low or negative worth to itself, but high worth to another system. Similarly, two people may help each other to cut down some trees because one wants the timber and the other wants to farm the land. Each acquires something different from the interaction that is worth more than he/she put into it. Cooperation and exchange between systems is based on such differences in values.

Cooperation between systems is defined as joint or coordinated behavior that results in a sharing of outcomes that are of greater worth to the systems than they could have obtained separately. Cooperation results from a condition in which two or more systems can help each other to achieve their purposes and goals. In biology this condition is called symbiosis.

Compromise, on the other hand, does not result in greater worth to each system than it could have obtained separately, if other systems were not contending for the same resources. But it does avoid the costs of overt conflict and usually results in a sharing of resources that, because of differing values, is perceived as mutually beneficial.

Cooperation is based upon the benefits of exchange between systems. Sharing or compromise in the distribution of uncontrolled resources and the determination of environmental conditions permits two or more systems to occupy the same niche. But sharing of inputs obtainable from the nonliving environment is usually not sufficient for all purposes. Exchange is a vital part of the input and output processes of living systems.

Life forms long ago found many advantages in intersystem exchange. Often the continuing nature of these advantages caused systems to form higher-level suprasystems capable of maintaining and coordinating the exchange relationship.

Are there specific characteristics of an exchange relationship that induce conflict or cooperation? How do living systems attempt to manage conflict? How can systems promote increased cooperation in the distribution of resources? These are some of the questions that this paper will seek to answer.

Resource and Environmental Conflict

Resource conflict may be over uncontrolled scarce resources in the environment or resources controlled by the contending systems. In the first case the direct action of each system is upon the nonliving environment, but interaction between living systems is required in order to determine how much of the resources each system can obtain. As systems gain control of the resources, the situation devolves into the second case, in which systems attempt to obtain resources from each other. This most often occurs through exchange, in which each system gives up certain resources in order to gain others. Another possibility, however, is domination whereby one system obtains resources from another without giving similar worth in exchange.

Environmental conflict is similar in nature to conflict over uncontrolled resources, except that the goal is a particular environmental condition rather than a resource input. For example, Canada and the United States are currently in conflict over acid rain. Manufacturers in the U.S. are in conflict with the government of Japan over the rules and regulations governing imports into Japan. An individual is in conflict with her neighbor over the volume of sound produced by the neighbor's stereo.

Power

With respect to competition for uncontrolled resources and conflict over environmental conditions a primary mode of conflict resolution is the application of power. The relative power of the contending parties or the power of a third party or suprasystem may decide the issue. The United States may continue to pollute the air over Canada with sulfur dioxide because Canada lacks the power to force the U.S. to do otherwise. The U.S. may likewise lack the power to influence a change in Japanese trading rules. Neighbors may summon police power to resolve the issue of noise pollution.

Of course, a negotiated settlement is also possible. There have been negotiations between Canada and the U.S. concerning acid rain, and between the U.S. and Japan over trade restrictions. Even though the power balance permits domination or effective resistance by one party, the desire for cooperative relations in other matters may induce the parties to try to arrive at a compromise or contrive a cooperative solution. In the case of trade restrictions, for instance, both the U.S. and Japan may benefit economically from reciprocal reduction of trade barriers.

A difference in values may aid the process of finding a mutually beneficial solution. The U.S. has excess capacity in agriculture and certain natural resources, but sets a high value on certain electronic goods. Japan has excess capacity in electronic manufacturing, but requires imports of agricultural products and natural resources. Under such circumstances it should be possible to negotiate a mutually beneficial settlement.

When different environmental conditions are combined in this way to form a negotiated settlement, the case begins to resemble an exchange of resources between systems. Conflict over resources already possessed or controlled by systems involves such a process of exchange. The terms of exchange are usually negotiated.

Exchange between systems takes many forms. First, there is the question of what is exchanged. It may be matter, energy, information or any combination of these. The exchange does not have to be symmetrical. Matter may be exchanged for information, as when goods are purchased with money. Or information may be traded for energy, as when a leader explains a plan and the subordinates carry it out.

Second, the resources or benefits that one system offers to another may be of positive or negative worth, both to itself and the other system. The most stable, cooperative exchange relationships stem from a situation in which each system is able to trade its excess resources (i.e. resources of negative worth to itself) to a system that places a positive value on them. For example, a manufacturing firm typically has little use for its own wares, but potential customers many value them highly. If those customers have spendable income, which the firm desires, the conditions for a mutually beneficial trade exist. The rebates, low-interest loans and other gimmicks that auto dealers use to unload inventory when the model year changes are a vivid illustration of this condition.

When a system must offer resources of positive worth to itself, cooperation is still possible provided that it receives resources of greater worth in exchange. The customers in the example above probably set a positive worth on their money, but the goods are perceived as having greater worth. Whether or not the resources have positive worth for both systems, cooperation depends on the net value of the exchange (i.e., the worth of what is received minus the cost, if any, of what is given). The net value must be perceived by both systems as positive, at least in the long term.

A condition of conflict exists when the net value of the exchange is negative for one or both systems. Conflict behavior is likely if the resources available for exchange are negatively valued by both systems. In that case it costs nothing to inflict punishment on the other system, although retaliation can be expected. One reason that armed conflict is so easy to fall into is that armaments, and even armies, have little intrinsic worth to the nation when they are not used. If the leaders of a nation come to believe that they will suffer little retaliation and much reward from attacking another nation, the net value of an attack may seem enormous. The argument for arming the nation, even with nuclear weapons, is based on the realization that only the certainty of retaliation may deter an attack, by lowering the perceived net value of that alternative.

Conflict can be quite stable, so long as each system gets rid of more negative worth than it absorbs from its opponent. If we could easily make war with sludge and other waste products, there would probably be no end to it. Fortunately, most things that could be used to punish or coerce another system also have some usefulness to ourselves. Thus, we might not want to waste the energy needed to dump the sludge on an opposing system. The steel in our weapons could be useful if beaten into plowshares. When a system must use resources of positive worth to itself in order to oppose another system, the net value of conflict and the likelihood of conflict behavior are diminished.

Conflict may appear profitable because it enables a system to obtain resources from the environment or a favorable exchange with a third system. Some exchanges become positive in value only when additional systems are involved. An exchange involving money or credit, for instance, would not be worthwhile to the recipient of the money if there were not another system willing to accept cash or credit in exchange for goods and services. In periods of very rapid inflation, in fact, this becomes a problem for exchange relationships based on money. The "full faith and credit" of the government is needed to make the monetary exchange system work.

Conflict behavior, in particular, is likely to assume positive net worth only when other relationships are taken into account. Two nations may find it useful to engage in armed conflict, even though each suffers damage at the hands of the other, because it solidifies their bonds with other nations and with their own citizens.

When one system stands to gain while the other loses, domination and exploitation are likely to occur. This exchange relationship is inherently unstable, however, because the losing system will seek to escape from it. Living systems must actively seek positive exchange, or else face extinction because of inability to replace consumed resources.

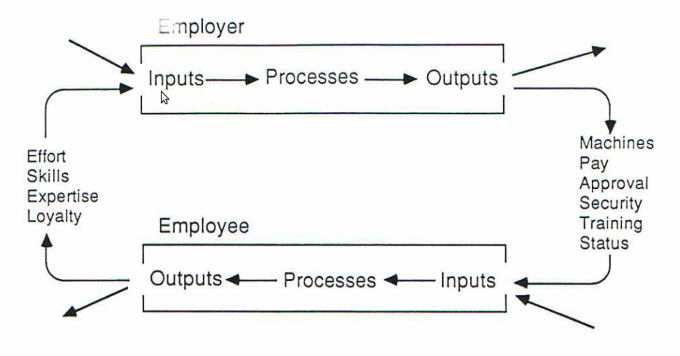

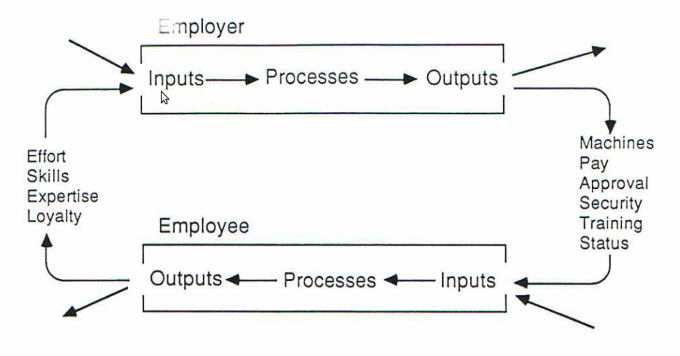

Bonding

Cooperative exchange between living systems tends to form a new dyadic system. Such a dyad may be represented as in Figure 1, which shows the exchange relationship between an employer and employee. A dyad of living systems is not necessarily a living system itself, but may become one if the relationship persists.

From L. Tracy, "A dynamic living-systems model of work motivation," Systems Research, 1984, 1, p. 201.

Figure 1 may be used to represent the degree of interdependency between systems. In addition to the exchange within the dyad, the figure indicates that there are inputs from and outputs to other systems. The number of such alternative sources and recipients, the amount and nature of resources they have available or require, the degree of substitutability of one resource for another, the storage capacity of each system, and the willingness and ability of each system to forego fulfillment of a need, if necessary, are factors that determine the degree of interdependency.

If system A is the only available source of a resource required by system B, there are no suitable substitutes, B has little storage capacity for the resource and is unwilling to do without it, then B is very dependent on A. System A would have considerable power over B in such a circumstance, but A may have a similar dependency on something supplied by B. When the dependency is mutual, a strong bond is formed.

Very long-lasting relationships may be built upon mutually net positive exchange between systems, even when the degree of interdependency is not high. If the exchange meets constantly recurring needs, a firm bond may be formed as a matter of convenience. Over time the terms of the exchange are codified and the bond becomes capable of replicating itself. When that happens, a new, higher-level living system has been formed.

The strongest bonds are found between components and subsystems of higher-level systems. The bonds between organs of an organism, members of a family, employer and employee, citizen and nation are based upon mutually beneficial, highly interdependent exchange. Even so, given that the components of these systems are themselves living systems with their own purposes and goals, conflict is still possible. Indeed, conflict may be intensified by the fact that bonding through interdependency has made withdrawal very difficult or impossible.

Other, less permanent relationships, such as between buyer and seller or audience and performer, are also built on mutually beneficial exchange. The relationship may lack permanency because the needs that are met are evanescent or because there are many other systems offering similarly beneficial exchanges. Most dyads of living systems form and dissolve very easily.

Perception is an important factor in social bonds. A conscious bond may be created so long as both parties perceive it to be mutually beneficial. Some bonds appear to be "odd couples" from the point of view of an observer. Although the mutual benefits of marriage as an institution are recognizable, it is often difficult to understand what two particular people see in each other. Indeed, they may come to the same conclusion after having a go at marriage for a while. But unconscious bonding may occur without perception, so long as it is mutually fulfilling, and may even persist without perceived benefit if the partners see no better options.

Theories of Exchange

There have been attempts to develop theories of exchange in such fields as physiology, sociology, economics and ecology. Exchange between human individuals as the basis for formation of groups was modeled by Homans (1958) and Thibaut and Kelley (1959). According to Homans the likelihood of bonding into a group increases as the amount of shared sentiments, activities, and interactions increases. Thibaut and Kelley proposed that affiliation with a group is based on a positive level (i.e. rewards greater than costs) of outcomes from the interaction. This is similar to the positive-net-worth-of-exchange criterion discussed earlier.

Adams' (1965) equity theory posits that an individual's motivation to work is based upon the ratio of exchange between the person and the employer, as compared with the perceived ratio for other employees. In other words, it is not simply a question of whether organizational rewards exceed personal costs. That may simply determine willingness to associate with the organization (i.e. take the job). How hard the employee is willing to work depends on how well his/her personal ratio of exchange compares with that of other employees. To put the idea more broadly, conflict between components develops if the system does not distribute rewards equitably, or at least ina manner that is perceived to be equitable.

Sources of power are based upon the anticipated worth of various sorts of exchange. Reward power stems from being able to offer resources that are worth more than the cost of compliance. Coercive power is based on the recipient's perception that compliance offers a better exchange (even if negatively valued) than does risking punishment through noncompliance. Authority is accepted only when subordinates believe they are receiving a reasonable exchange for their obedience.

Hollander and Julian (1969) based their theory of leadership on social exchange theory. In their view followers accord status, esteem and influence to the leader in exchange for the leader's aid in achieving group goals and fulfilling expectations of rewarding outcomes. Influence between leaders and followers is a two-way process.

Thus we see exchange theory employed to model a variety of interpersonal and intersystem processes. It may not be going too far to assert that positive exchange is the basis of all linkages between living systems. Because living systems seek to fulfill needs and to maintain a positive balance of inputs over outputs, it follows that they will be attracted to any relationship with another system that offers a favorable exchange, and opposed to any relationship offering a negative balance. This principle serves to explain bonding between living systems just as positive and negative charge explain chemical bonding between elements and compounds.

Managing the Exchange Relationship

Conflict potential may or may not be inherent in an exchange relationship between two systems. If the systems occupy the same niche, require the same resources, and the available resources are insufficient to fulfill both sets of needs, then the two systems are inherently in opposition. In such a situation conflict behavior is probable because it is the only way, other than finding a new niche, that either system can fulfill its needs.

Yet such a condition of absolute opposition is unlikely. Typically, there is inherent opposition over some resources and a potential for sharing or exchanging others. It then becomes a matter of the perceptions of both systems as to whether the potential for cooperation or withdrawal outweighs the advantages of conflict. Since a system never fulfills all of its needs, it may choose to act on those that can be fulfilled cooperatively. When alternative sources or substitutes are available, it may also choose to withdraw from the relationship and seek fulfillment elsewhere.

Likewise, a situation in which two or more systems may benefit from interaction does not guarantee cooperation. To cooperate, the systems must perceive the opportunity and must agree on terms of the interaction, or else must fall unconsciously into a mutually beneficial exchange through a process of trial and error. Conscious cooperation is commonly achieved through a process of negotiation or mutual decision making. Part of the process may involve making each other aware of the potential benefits of cooperation.

Regardless of the potential for conflict or cooperation, therefore, the interaction between living systems can be managed. Power and communication may be used to influence perceptions of the situation. Each system may choose to emphasize the potential for opposition or mutual benefit. And each system may choose a strategy of collaboration, sharing, domination, appeasement, or avoidance (Thomas 1983: 900).

The choice of strategy is likely to be influenced by the size and level of the interacting systems, as well as the degree of trust between them. Systems of equal size and level but lacking trust (e.g. the U.S.A. and the U.S.S.R.) are likely to choose a strategy of negotiation toward sharing or compromise. They lack the power differential for domination and appeasement, the degree of trust required for collaboration, and (in the chosen example) the room for avoidance. Where there is greater trust, as between members of the European Common Market, negotiation toward collaboration is more likely.

Interaction between systems of different size or level is likely to result in a strategy of domination and appeasement, avoidance (if possible), or formation of a coalition followed by negotiation. The coalition strategy is illustrated by formation of a labor union to enable individual employees to negotiate with their employer. Although labor negotiations are often viewed as interaction between two organizations, the union and the firm, the primary beneficiaries on the labor side are the individual employees. Without the coalition their only viable strategies would be appeasement or avoidance.

Systems at different levels often manage to collaborate despite the disparity of power. Provided that avoidance is a workable option and a condition of cooperation (i.e. potential for mutual need fulfillment) exists, a mutually satisfactory agreement may be reached even through a strategy of domination and appeasement. Many individual employees willingly submit to the conditions of employment dictated by their employer, because those conditions fulfill certain needs and are better than the immediate alternatives. When another firm offers better conditions, the employees are free to move.

The existence of a mutual suprasystem provides other means of managing the interaction. An employee who feels he or she has been the victim of discrimination or harassment can appeal to a government agency or court for relief. As the government holds power over both the individual and the organization, it may ordain mediation or arbitration to settle the dispute. The presence of a mediator representing the suprasystem mitigates the power differential between systems at different levels, whereas arbitration substitutes the power of the government for the power of the parties.

When one of the contending systems is the suprasystem of the other, a different form of management is necessary. The marketing department of a corporation, for instance, is an integral part of the organization and cannot withdraw. Refusal of the department to cooperate with organizational policy would cause injury to itself as well as the firm. Under such a condition of subordination, negotiation toward collaboration is the usual strategy, with appeal to the CEO as arbitrator often being a final alternative.

There are two common threads running through this discussion of conflict management. One is the theme of power equalization. Roughly equal power encourages negotiation toward compromise or collaboration. Large power differentials stemming from subordination, or differences in size or level, encourage domination and appeasement. Ability to withdraw or avoid interaction, to form a coalition, or to appeal to a mediator or arbitrator may provide means for circumventing the power differential and enabling agreement on terms of interaction that are more mutually fulfilling. A subsidiary theme of trust influences the degree to which the systems are willing to increase the degree of their interdependency.

The other major theme is the condition of conflict or cooperation in which the systems find themselves. The strategy of collaboration depends on the existence of differences in needs and values such that a mutually fulfilling exchange can occur. Two firms that both manufacture shovels probably have little potential for cooperative exchange. A woodworking firm that makes handles and a metalworking firm that can produce blades may have considerable cooperative potential, however. A giant corporation and an individual employee may engage in cooperative interaction despite the differential in level, size and power, simply because each values highly what the other has to offer.

A generic study of conflict and cooperation in exchange between living systems would focus on these two themes. The theme of power equalization leads to measurement of variables such as relative size, system level, subordination, possibility of withdrawal or coalition formation, trust, and degree of interdependency. The theme of conditions underlying the exchange focusses on what each systems stands to gain and lose through interaction, on differences in needs and values, and on alternative sources of fulfillment.

These themes strongly affect the choice of strategy in interaction between living systems, as well as the means used to implement the strategy. Given that power and conditions of exchange are perceived variables in conflict management, a subsidiary theme would be the management of perceptions through communication and influence.

In fact most of the variables cited above, as well as relationships noted between them, already are the subject of study at the several levels of research on conflict management. The contribution of living systems theory is to provide a framework for understanding the generality of these variables and relationships, and their sources in the common characteristics of living systems. Additionally, the theory spotlights certain aspects of system interaction, such as subordination and cross-level negotiation, that normally receive little attention.

References

Adams, J. S. 1965. Inequity in social exchange. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology, Vol. 2, 267-299. New York: Academic Press.

Hollander, E. P., and Julian, J. W. 1969. Contemporary trends in analysis of leadership processes. Psychological Bulletin 71: 387-397.

Homans, G. C. 1958. Social behavior as exchange. American Journal of Sociology 63: 597-606.

Miller, J. G. 1978. Living systems. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Thibaut, J. W., and Kelley, H. H. 1959. The social psychology of groups. New York: Wiley.

Thomas, K. W. 1983. Conflict and conflict management. In M. D. Dunnette (Ed.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology, 889-935. New York: Wiley.

Tracy, L. 1983. Lack of leadership: a living systems perspective. In G. E.

Lasker (Ed.), The relation between major world problems and systems learning, 569-575. Seaside, CA: Intersystems.

Tracy, L. 1986. Toward an improved need theory: in response to legitimate criticism. Behavioral Science 31:205-218.