Back • Return Home

A Need-Goal-Path Model of Motivation within Organizations

by

Lane Tracy

Abstract

Current theories and models of motivation are incomplete and seemingly contradictory. Within the framework of living systems theory, however, it is possible to combine and integrate them into a single dynamic model. Such a model is presented here. It combines theories of needs, goal setting, expectancy, and reinforcement into a need-goal-path model of motivation, for an individual system. Through the concept of the systems dyad this individual model is then extended to show the lines of interaction between organizations and members concerning goals, paths, and outcomes. Some practical implications for organizational leaders are drawn from the dyadic need-goal-path model.

Motivation to perform organizational tasks is a topic of great interest to managers and administrators. Organizational leaders tend to believe that, if members could only be motivated more strongly in the right direction, their performance and the effectiveness of the organization would improve. Individual needs, organizational rewards, and communication are though to have something to do with motivating members, but the exact connections are uncertain. Every manager tends to have a private, experience-based theory about what motivates people.

Academics in the fields on psychology and organizational behavior, on the other hand, are apt to point out that individuals are always motivated. The question is only what they are motivated toward. If organjizational goals and rewards are sufficiently attractive, members will be motivated toward them. Thus, academics offer advice such as: Increase organizational rewards for performance; choose rewards that meet dominant needs; make the rewards more salient or more certain through communication; maintain equity of rewards; obtain commitment to organizational goals; increase the attractiveness of the organizational path to performance; and remove barriers in the path. These bits of advice are based on such theories as the need hierarchy (Maslow, 1943; Alderfer, 1972), expectancy theory (Vroom, 1964), goal-setting theory (Locke,1968), equity theory (Adams, 1963), path-goal theory (Georgopoulos, Mahoney & Jones, 1957; Evans, 1970; House, 1971), and the job characteristics model of Hackman and Lawler (1971).

Although the various theories and models of motivation are certainly useful, they offer a confusing and perhaps incomplete picture. A practitioner may have reasan to ask such questions as: Which is more important, reward or goal commitment? Why does employee motivation change over time? Why does a reward (or path) have differing value for different individuals? How can equity be maintained in such a situation?

This paper does not promise to answer all such questions, but it may shed light on the interconnections of various theories and models. The paper will briefly develop a model of individual motivation that incorporates the concept of need as the determinant of goal valences. The model also separates goals from outcomes and outlines the role of feedback from outcomes to the motivational decision-making process. This individual motivation model is then put in the context of an organization which attempts to influence the individual's choice of goals, defines the path to goal attainment, and apportions rewards.

The whole model is imbedded in the framework of living systems theory (Miller, 1978). Individuals, groups, and organizations are all living systems with many characteristics in common. In particular for our purposes, both individuals and organizations have needs and goals which can be fulfilled by means of cooperation and exchange. Thus, the final model will show the motivation processes of individuals and organizations as parallel systems with many points of interaction. It is hoped that this model will fill in some of the gaps that presently exist in our understanding of motivation in organizations.

Motivation

Motivation is a psychological construct used to explain why people behave as they do, why they perform one act and not another. Motivation is inferred from behavior; it cannot be seen directly. It consists of at Jeast two distinct aspects, (1) the energizing of behavior and (2) the direction of behavior. A third aspect, the maintenance of behavior over time, is sometimes included.

Although the concept of motivation is usually applied only to organisms, it can be used more generally to understand the "behavior" of groups and organizations. All living systems act upon their environment in their own interests, and the concept of motivation may be used to interpret this behavior.

According to living systems theory (Miller, 1978, pp. 34-41), individuals and organizations have certain values built into their templates (i.e. their genes or the corporate charter). These values may be modified and new values acquired through learning. Needs and goals are determined by specific preferred steady-state values called purposes. Around each purpose there is a range of stability. A need is associated with a strain or tension that occurs in a system when the status of a particular resource falls below its range of stability. At that point a feedback signal is sent to the decider subsystem (Miller, 1978, pp. 67-68), which chooses whether and in what manner to respond to the deficit. The reaction of the decider may be automatic, as when the human body responds to a lack of heat by shivering and constricting the capillaries, or it may be a conscious choice as when in the same situation the person puts on a sweater. In either case, the person has been motivated to respond to a need.

In a similar fashion, an organization may be motivated to respond to a lack of cash by automatically drawing upon a line of credit, or it may consider other responses such as issuing stock or selling a division. The point is that motivation is basically a process of decision making in response to needs. The decider chooses which needs will have priority, how they will be fulfilled, and how much fulfillment will be pursued before other needs are attended to.

Individual Motivation

Theories of individual human motivation are often divided into categories, such as content and process theories or drive and reinforcement theories. Content theories, such as the need theories of Maslow (1943) Alderfer (1972), and McClelland (1961), focus on need as activators of tensions which influence the choice of behavior and its intensity and duration. Process theories such as Adams' (1963) equity theory, Vroom's (1964) expectancy theory, and Locke's (1968) goal-setting theory focus instead on the processes by which goals and behavior are chosen and maintained. Drive theories (e.g. Murray, 1938) posit motives that are built into the system, whereas reinforcement theories (e.g. Thorndike, 1911; Skinner, 1953) emphasize the role of extrinsic rewards in shaping behavior.

It is the viewpoint of this paper that all of these theories are correct in part, but that all of them see only part of the picture. Both content and process are necessary. For example, expectancy theory focuses on the perceived valences of outcomes, but ignores the fact that these valences are influenced by needs. Goal-setting theory notes the motive power of goal commitment without considering the purposes behind the goal. On the other hand, need theories often confuse needs with the processes of fulfillment, thereby muddling the concept and perhaps rendering it useless, as Salancik and Pfeffer (1977) and Tracy (1983a) have suggested. Drive and reinforcement theorists often seem unwilling to admit that they may both be right, that needs and responses may be both innate and learned.

Expectancy Theory. Let us start with expectancy theory as a basis for building a more complete picture of motivation. According to Vroom (1964) the strength of motivation toward any particular act is dependent upon (1) the perceived probability (expectancy) that the act will achieve a desired outcome or outcomes and (2) the perceived worth (valences) of those outcomes. This simple model may be expressed by the equation

M = (V1 × E1)

where M = strength of motivation toward a particular act, V1 = the valences of first-level outcomes, and E1 = the expectancies of those outcomes.

A first-level outcome, such as performance of a task, leads to second-level outcomes such as monetary reward and recognition. Thus, the valence of a first-level outcome is dependent not only on its intrinsic worth to the individual, but also on the perceived likelihood (instrumentality) that it will lead to second-level outcomes and the valences of those outcomes. Expressed as an equation,

V = IV1 + (V2 × I2)

where IV1 = the intrinsic valence of the first-level outcome, V2 = the valences of second-level outcomes, and I2 = the perceived instrumentality of the first-level outcome toward the attainment of the second-level outcome.

This model has received considerable attention because it is intuitively reasonable. It is difficult to test empirically, however, and research results have generally not supported the multiplicative relationships in the model (cf. Heneman and Schwab, 1972; Mitchell, 1974; Wahba and House, 1974; Connolly, 1976; Mitchell, 1980). Other shortcomings of the model are that it is static; it does not explain the source of valences, expectancies, and instrumentalities or the mechanism by which they change with experience. For example, the model does not account for the fact that an organism's motivation to pursue a given outcome tends to decrease as that outcome is attained. The difficulty is that the model remains rooted in expectations with no feedback from actual outcomes.

Extending the Model. Let us extend the model in two ways. First, let us add needs to the model. A need is defined here as "matter-energy or information that is useful or required but potentially lacking in some degree according to a purpose of a living system" (Tracy, 1983a, p. 598). When a need is actually lacking, it is said to be manifest. Needs may be innate or learned. Needs vary in intensity (degree of deficit) and importance. The importance of a need depends on the consequences to the system if it continues to be lacking. A need may be considered to be "an objective requirement [of the system] to avoid a state of illness" (Mallmann and Marcus, 1980, p. 165).

Needs determine valences. When a particular first or second-level outcome is perceived as fulfilling one or more manifest needs of the system, its valence will tend to be high. As those needs are fulfilled, the valence of that outcome will decrease. Thus, the need concept helps not only to explain the source of valences, but also to account for the fact that motivation decreases as the goal is attained.

The second extension of the model is to add actual behavior and outcomes, with feedback loops to the decision making stage of the model. Actual outcomes change the intensity of needs, as indicated above, and thereby modify valences. In addition, success or failure in attaining first-level outcomes confirms or modifies expectancies, and attainment of second-level outcomes confirms or modifies instrumentalities.

Since the term "outcome" fits the actual events, let us call the anticipated outcomes "goals". Goals are latent when they are simply being considered as action alternatives, but they become manifest when they are chosen. Commitment to a given goal may be increased by intensifying the needs that it fulfills and/or by strengthening the expectancy and instrumentality of the goal. Thus, goal-setting theory (Locke, 1968) and expectancy theory seem to merge when a distinction is made between goals and outcomes.

The extended model of individual motivation is shown in Figure 1. The module within the dashed lines represents the original expectancy theory.

Figure 1. Need-goal-path model of individual motivation.

Motivation toward Organizational Performance

The model shown in Figure 1 applies as well to organizations. Executives comprise the upper echelons of the decider subsystem of an organization. These executives (1) perceive various organizational needs, (2) establish valences of goals based on these needs, (3) choose actions based on a rational model of valences, expectancies, and instrumentalities; and (4) issue orders for the execution of the choosen actions. Decisions are modified on the basis of feedback from outcomes.

The point of interest here is the interaction between an organization and the individuals who must execute these organizational decisions. Both the organization and the individual member have needs. The continuing relationship between organization and individual is based on mutual need fulfillment. The individual member supplies the organization with labor, skill, expertise, loyalty, acceptance of authority, attendance, perhaps even tools. In return the member may receive pay, recognition, security, supervision, training, tools, machinery and the energy to run it, safe and healthful working conditions, status, and loyalty.

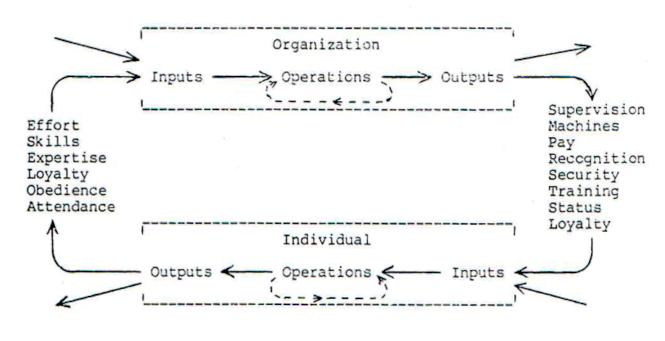

Systems Dyad. This mutual exchange of needed resources between the two systems may be pictured in the form of a systems dyad (Figure 2). Note that each system has alternative sources for need fulfillment, such that their mutual dependency is not total.

Figure 2. Systems dyad.

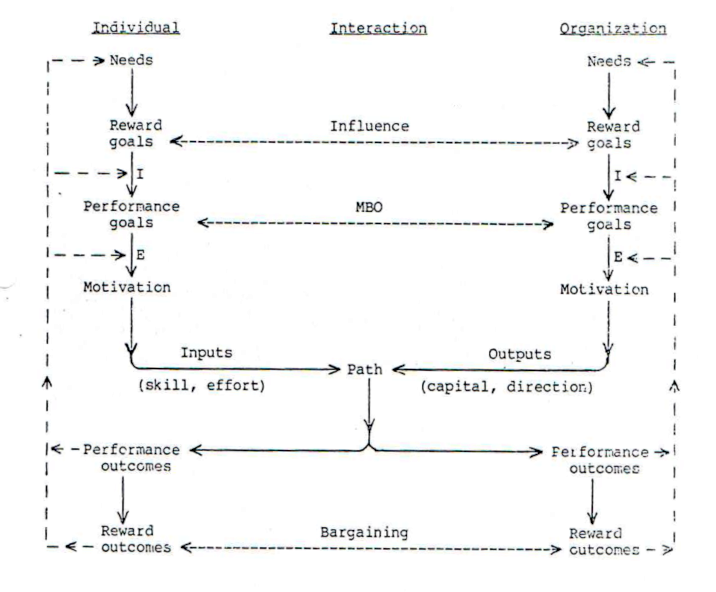

An important aspect of the relationship between an organization and its members or employees is that the latter cede some decision making to the organization. Individuals accept the legitimacy of orders (within limits) from the organization and agree to carry out the specified actions. Motivation of an individual's behavior still comes from the individual, but it is more or less strongly influenced by the organization. To the extent, for instance, that an individual accepts the organization's goals as his/her own goals, their valences for the individual are enhanced. Processes such as Management by Objectives (MBO) or participative decision making may be used to increase individual acceptance of organizational goals. It should not be overlooked, however, that these are two-way processes in which individuals may have some influence on organizational goals.

Individual and organization merge at the stage of performance of directed behavior. The amount of effort and skill that the individual puts into the task contributes to organizational performance and outcomes. Likewise, the quality of supervision and amount of capital investment that the organization puts into the task contributes to the individual's performance and outcomes. Just as the organization may attempt to influence an individual's motivation in order to increase his/her contribution to the task, so the individual has an interest in inducing the organization to increase its contribution.

Although the individual and organization receive different outcomes from their joint performance, these separate outcomes represent a division and sharing of the overall outcomes. Collective bargaining or individua contract bargaining may be used to set the terms for this division. Again, each party to the dyadic relationship has an interest in influencing the division of the joint outcome.

The dyadic relationship may be expanded as in Figure 3. This model emphasizes the parallel nature of motivational processes in the two systems, and specifies some of the points of mutual influence and interdependency between them.

Figure 3. Dyadic need-goal-path model of motivation.

The need-goal-path models presented in Figures 1 and 3 are preliminary attempts to formulate a dynamic, comprehensive theory of work motivation Much additional conceptual and empirical work is needed. Because the models integrate several existing theories of motivation, however, they are already supported by much of the empirical work done to test these. separate theories. For instance, the models are able to account for research findings of Porter and Lawler (1968) with respect to pay as a motivator. Indeed, many aspects of the Porter and Lawler model, including a feedback loop, are incorporated in the need-goal-path models.

Practical Implications of the Models

The model shown in Figure 3 contains several practical implications for organizational policy and development. First, unlike traditional models of motivaton, it emphasizes that motivation is a two-way street. Members individually and collectively seek to motivate the organization to do certain things just as the organization seeks to motivate individual and group performance.

Furthermore, the model makes clear that performance is dependent on both individual and organizational contributions. Managers, in seeking greater input of effort from employees, often overlook the fact that poor supervision or poorly maintained machinery is wasting much of the existing effort. Employees, on the other hand, may be well aware of that fact but have been discouraged from communicating it to organizational decision makers. Recent innovations in management such as Quality Circles and Quality of Work Life experiments are based on tapping the expertise of employees to reduce such waste. The motto of Quality Circles is "Work smarter, not harder!"

The motivation for employees to contribute ideas that will improve organizational efficiency is already present. Most employees are able to see that improved performance, so long as it does not have a high cost, will enhance fulfillment of their own goals. Motivation will be increased if the organization is willing to add second-level rewards such as recognition and bonuses for worthwhile suggestions.

The level of effort contributed by individual employees is based on their calculation of the valence of goals, the likelihood of attaining them, and the equity of the exchange. An organization can increase individual motivation by influencing the calculation at any of these points. For instance, through coaching or clarification of instructions a supervisor may increase an employee's expectancy that he/she can attain a performance goal and thereby gain additional rewards. Likewise, the instrumentality of task performance for the employee may be strengthened by a firm promise of reward for performance and consistent fulfillment of that promise. The model emphasizes the influence of feedback from actual outcome on assessment of expectancies and instrumentalities, and thence on motivation.

Some of these same insights are provided by the path-goal theory of leadership (Georgopoulos et al., 1957; Evans, 1970; House, 1971). However, path-goal theory fails to distinguish clearly between organizational goals and individual goals. The path is seen as organizationally determined. The supervisor's role is to smooth and clarify the path, provide rewards for good performance, and emphasize the value of those rewards. In contrast, the model above suggests that defining and clarifying the path, smoothing it, and determining appropriate and equitable rewards is a mutual process between employees and organizational leaders. To the extent that supervisors attempt to make this a one-way process, they are likely to shut off valuable inputs and adversely affect employee motivation.

The major role of organizational leadership is to set appropriate goals and provide efficient plans for attaining them. The goals should take into account the needs of both the organization and its members (Tracy, 1983b). The plans should make good use of the resources at hand, and should not waste the inputs of either the organization or its members. Consultation with members is required in order to understand their needs, gain their commitment to organizational goals, and obtain their ideas about efficient use of resources. This may not be leadership in the heroic mold (Jennings, 1960), but it is the sort of leadership required in a democratic society in which organizations and individuals have relatively equal claims to survival and fulfillment of their needs.

References

Adams, J. Stacy. "Toward and Understanding of Inequity." Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 67 (1963): 422-436.

Alderfer, Clayton P. Existence, Relatedness, and Growth. New York: Free Press, 1972.

Connolly, Terry. "Some Conceptual and Methodological Issues in Expectancy Models of Work Performance Motivation." Academy of Management Review 1 (1976): 37-47.

Evans, M. G. "The Effects of Supervisory Behavior on the Path-Goal Relationship." Organizational Behavior and Human Performance 5 (1970): 277-298.

Georgopoulos, Basil S., Mahoney, G. M., & Jones, N. W. "A Path-Goal approach to Productivity." Journal of Applied Psychology 41 (1957): 345-353.

Hackman, J. Richard & Lawler, Edward E., III. "Employee Reactions to Job Characteristics." Journal of Applied Psychology Monograph 55 (1971): 259-286.

Heneman, Herbert G., III & Schwab, Donald P. "Evaluation of Research on Expectancy Theory and Predictions of Employee Performance." Psychological Bulletin 78 (1972): 1-9.

House, Robert J. "A Path Goal Theory of Leader Effectiveness." Administrative Science Quarterly 16 (1971): 321-338.

Jennings, Eugene E. An Anatomy of Leadership. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1960.

Locke, Edward A. "Toward a Theory of Task Motivation and Incentives." Organizational Behavior and Human Performance 3 (1968): 157-189.

Mallmann, C. A. & Marcus, S. "Logical Clarifications in the Study of Needs." In K. Lerder (Ed.), Human Needs. Cambridge, MA: Oelgeschlager, Gunn, and Hain, 1980.

Maslow, Abraham H. "A Theory of Human Motivation." Psychological Review 50 (1943): 379-396.

Maslow, Abraham H. Motivation and Personality, 2nd ed. New York: Harper & Row, 1970.

McClelland, David C. The Achieving Society. Princeton, NJ: Van Nostrand, 1961.

Miller, James G. Living Systems. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1978.

Mitchell, Terence R. "Expectancy Models of Job Satisfaction, Occupational Preference and Effort: A Theoretical, Methodological and Empirical Appriasal." Psychological Bulletin 81 (1974): 1053-1077.

Mitchell, Terence R. "Expectancy-Value Models in Organizational Psychology." In N. Feather (Ed.), Expectancy, Incentive and Action. New York: Erlbaum and Associates, 1980.

Murray, Henry A. Explorations in Personality. New York: Oxford, 1938.

Porter, Lyman w. & Lawler, Edward E., IIT. Managerial Attitudes and Performance. Homewood, IL: Richard D. Irwin, 968.

Salancik, Gerald R. & Pfeffer, Jeffrey. "An Examination of Need Satisfaction Models of Job Attitudes." Administrative Science Quarterly 22 (1977): 427-456.

Skinner, B. F. Science and Human Behavior. New York: Macmillan, 1953.

Throndike, E. L. Animal Intelligence. New York: Macmillan, 1911.

Tracy, Lane. "Basic Human Needs: A Living Systems Perspective." In George E. Lasker (Ed.), The Relation between Major World Problems and Systems Learning. Seaside, CA: Tntersystmes, 1983a, 995-601.

Tracy, Lane. "Lack of Leadership: A Living Systems Perspective." In George E. Lasker (Ed.), The Relation between Major World Problems and Systems Learning. Seaside, CA: Intersystems, 1983b, 569-575.

Vroom, Victor H. Work and Motivation. New York: Wiley, 1964.

Wahba, Mahmoud A. & House, Robert J. "Expectancy Theory in Work and Motivation: Some Logical and Methodological Issues." Human Relations 27 (1974): 121-147.