Back • Return Home

Living Systems Theory Applied to Organizational Behavior

Lane Tracy

Ohio University

Living systems theory (LST) provides an almost ideal theoretical and conceptual framework for the field of organizational behavior (OB). OB is concerned primarily with three of the eight levels of living systems, as shown in Figure 1 (Miller and Miller 1990).

Figure 1. Levels of living systems.

Individual human organisms (i.e., people), groups, and organizations are the focus of OB, with some consideration given to the community and society as suprasystems. Typically, however, each of these levels is treated separately and from a different theoretical perspective. Historically, the field of organizational behavior evolved from other social sciences to fill a need for practical knowledge about how people behave in organizations. Theories and research results were borrowed from such fields as clinical, experimental, industrial, and social psychology, as well as from sociology, economics, education, communication, and political science.

The problem is that each of these fields has its own set of concepts and terms, making it difficult to integrate ideas from one field with those from another. For instance, the concept of motivation (individual level) is not easily associated with communication networks (group level) or with organizational power and politics (organization level), even though these higher-level phenomena might be better understood as motivated behavior. The typical OB textbook begins with individual behavior, proceeds to group behavior, and then to organization structure and processes. Little attempt is made to loop backward in order to integrate concepts; they are simply piled on top of each other.

Even within levels there is lack of integration. Perception, learning, motivation, and decision making are obviously interrelated topics, yet they are typically treated in separate chapters, using theories, concepts, and terms that are not easily related to each other.

As I will demonstrate, LST provides a framework that permits us to integrate these topics. The emphasis in LST on critical subsystems and generic terminology allows us to treat each of the topics in a way that highlights their interconnections. Also, LST allows us to approach all levels simultaneously from a common perspective. Such an approach enriches our understanding of system behavior at each level, and facilitates analysis of interactions between levels.

Examples of LST applied to OB

The best way to demonstrate the value of LST as a framework for OB is to give some examples of its use. Among the usual OB topics to which LST has already been applied are: perception, learning, attitudes, needs, motivation, goal setting, decision making, leadership, group cohesiveness, socialization, roles, communication networks, conflict and cooperation, stress, power and politics, authority, influence, control, organization structure and design, specialization, environmental demands, culture and personality, and development.

Critical Subsystems and OB Topics

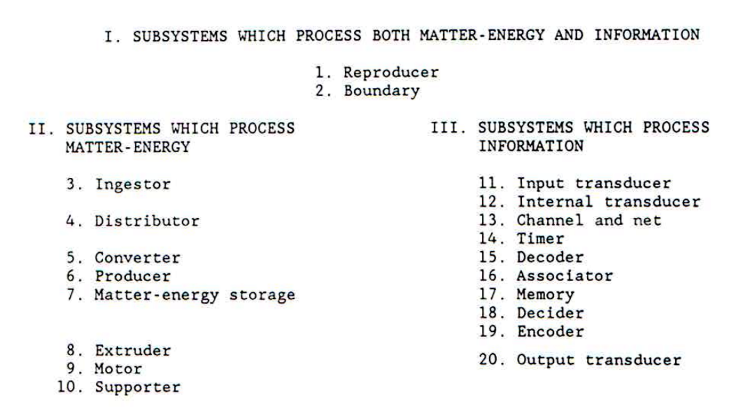

Most of the traditional OB topics deal with information processing. Thus, a good place to start is with the set of critical subsystems that process information, as shown in Table 1. The set includes the input transducer, internal transducer, decoder, timer, channel and net, memory, associator, decider, encoder, and output transducer, as well as the boundary and reproducer. The matter-energy processing subsystems are also involved in such OB topics as organization structure and staffing.

Table 1. Twenty Critical Subsystems of a Living System.

Organization structure. At the macro level OB is concerned with structural elements such as specialization, departmentation, and the hierarchy of authority. The departmental structure of organizations typically does not correspond closely to the critical subsystems, any more than the set of human organs does. Nevertheless, organizations must possess or have access to all of the critical subsystems. Furthermore, each of the processes of these subsystems must be effective.

Nothing in the traditional OB approach provides any indication of what constitutes complete coverage of the field. Consequently, new topics such as stress, culture, and organizational learning are regularly being added. The set of critical subsystems and processes would provide a framework for assessing the completeness of our coverage of behavioral processes in organizations. Merker (1987), for instance, has developed a survey approach, called living systems process analysis, which assesses the performance of the critical subsystems in an organization. This approach deserves to be incorporated into the OB literature.

The hierarchy of authority stems from the echelons of the organization's decider subsystem. An organization chart is basically a map of the formal decider subsystem, showing the echelons and the links between them. The decider is at the heart of OB, involved in most of the behavioral processes, because it is the locus of the process by which acts are chosen. Such choice is required for all purposeful behavior, including perception, learning, communication, conflict, influence, and change processes.

Perception. Perception is functionally selective (Berelson and Steiner 1964: 101-104). As Miller (1978: 97) puts it, "A system gives priority to information which will relieve a strain (i.e., which it ‘needs'), neglecting neutral information. It positively rejects information which will increase a strain." In other words, perception is a motivated process involving choice.

Perception is centered in the decoder subsystem, with links to the transducers, memory, and the decider through the channel and net. Signals from the input and internal transducers are compared with codes stored in memory. When a match is found, a signal is "recognized" or perceived.

Miller (1978: 402-404) included a discussion of perception in his chapter on organisms. Yet many principles of perception are applicable to groups and organizations, which typically disperse the process to individual members. For instance, business organizations select information according to its salience and usefulness, just as individuals do. Miller also noted that language, a societal characteristic, may influence perception through the codes it provides for various phenomena (Miller 1978: 793). Thus, an LST approach to perception should provide a fuller understanding of the process at all levels of an organization.

Learning. Learning is closely linked to perception. Although some codes (e.g. for taste, pitch, color) appear to be inmate, language and other codes used to recognize a signal are learned. That means, for instance, that associations are formed between sound patterns (i.e. words) and objects or actions, and these associations are stored in memory. When signals are received through an input transducer from a similar object or action, they are compared with the stored associations. If a match is found, the associated word is also evoked and influences the perception of the phenomenon. Similarly, a signal that is recognized as a word may evoke an image of the associated phenomenon.

Learning is a two-stage process involving the associator and memory subsystems. The associator forms enduring links or associations among items of information. These associations are then read into memory along with the original items of information (Miller 1978: 407).

A key contribution of LST to the topics of perception and learning is the recognition that these processes apply to social systems (i.e. groups, organizations, communities, societies, and supranationals) as well as individual organisms. The processes are generally dispersed downward to the level of individual members, but they are carried out in accordance with the purposes and goals of the host system. For instance, work-group members often learn a jargon peculiar to their craft and then perceive work problems in terms of the concepts associated with the jargon. They also learn particular ways of organizing and carrying out the tasks of the group, often through cooperation that was not specified by the suprasystem. These work methods are taught to new members but not to nonmembers, indicating that the methods are the property of the group, not the individual members.

In the past decade organization theorists have become interested in the process of organizational learning, whereby organizations learn from their mistakes and successes as well as by imitation of others (Shrivastava 1983). Stories about ideas that were tried and failed, or new products that sold better than expected, become part of the organizational memory. When a similar problem or opportunity arises, it is perceived in terms of the previous experience of the organization. The actual memory of these events resides in the many individuals who make up the organization, of course, but it is a shared memory and it results in decisions taken jointly to effect organizational purposes and goals. Thus, individuals and groups act as agents of the organization in this process.

The learning processes of individual organisms have been extensively studied, and knowledge of these processes is applicable at social-system levels. Yet the learning process of organizations is more than the sum of the individual parts. It includes elements of communication and conflict that, if they are present at the individual level, are seldom studied. For instance, different parts of an organization may come to different conclusions about the same event. From the failure’ of a new product the marketing department may "learn" that the engineers need to pay more attention to marketing studies on what the customers really want. The engineering department, on the other hand, may "learn" that the marketers don’t know how to sell a good product. Does this sort of conflicted learning occur within organisms? Anyone who has wrestled with learning to swing a golf club would be inclined to say yes. If so, the accessibility of learning processes in social systems may provide opportunities for learning more about the process at the individual level.

Needs and motivation. Needs and motivation have long posed problems for OB. Borrowing from other fields, OB has perpetuated a conglomeration of controversial concepts and theories that do not mesh well with each other. Although LST makes it obvious that living systems at all levels exhibit motivated behavior, motivation has been studied almost exclusively as a phenomenon of organisms. The same is true of needs, even though in everyday language we apply the term "need" to groups, organizations, and societies, as in "Our baseball team needs another starting pitcher."

Need theory, as promulgated in OB texts, has suffered from a variety of different concepts of need. There are "drive" theories (Murray 1938; McClelland 1961) which are really theories of motivation; "satisfaction" theories such as motivator-hygiene theory (Herzberg, Mausner, and Snyderman 1959); and "requirement" theories (Maslow 1943; Alderfer 1972). There have been strong criticisms of the research on each of these theories (Salancik and Pfeffer 1977; Mitchell 1979; Tracy 1986). The criticisms of need theory in general include:

1. The need concept is not well defined;

2. It is based on unproven and unexamined assumptions;

3. Descriptions of needs and need categories are ambiguous;

4. Lists and categories of needs are incomplete;

5. The origin of needs is disputed;

6. The concept implies a lack of human adaptability;

7. There is little empirical evidence for the currently popular need theories (Tracy 1986: 205).

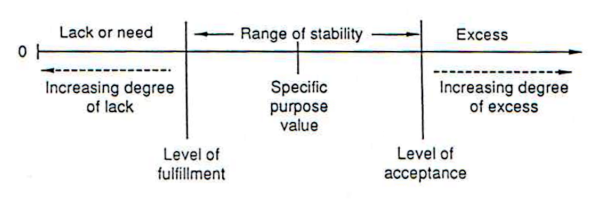

One reason for the profusion of conflicting need concepts is the lack of any central theoretical framework for OB. Employing LST as a basic framework, need can be defined clearly for any living system as "a lack of a specific resource which is useful for or required by the purposes of that system" (Tracy 1986: 212). Figure 2 shows how need relates to purpose under this definition.

Figure 2. The Resource Need Continuum.

Source: From Tracy (1986: 211).

This definition of need requires only the basic assumptions of living systems theory that such systems have purposes and require inputs to attain those purposes. The origin of needs is the template of the system, which specifies purposes. Since purposes can also be learned and modified through learning, the definition implies no lack of adaptability. It implies no lists or categories other than those that might apply to system purposes. Finally, the definition applies to all living systems, not just to human individuals.

The treatment of motivation in OB suffers from a similar profusion of theories and concepts. A typical OB textbook cites Adams’ (1963) equity theory, Locke's (1968) goal-setting theory, Vroom's (1964) expectancy theory, and path-goal theory (Evans 1970; House 1971), as well as some of the need theories discussed above. Reinforcement theory (Skinner 1953) could be added here, since it deals with motivation to continue or repeat an act, but reinforcement is usually discussed in a separate chapter on learning. Each of these theories is couched in its own terms and has little or no reference to the other theories. Furthermore, each theory has its critics.

Motivation may be defined generally as "the processes of a living system that cause the arousal, direction, and persistence of its purposeful behavior" (Tracy 1989: 99). Except for the reference to living systems, this definition is in accord with those generally found in OB texts. The definition points to one of the sources of multiple theories. Some theories focus on arousal (e.g., "need" theories), some on direction (e.g., goal-setting and expectancy theories), and some on persistence (e.g., equity and reinforcement theories). A good theory of motivation, however, should encompass all of these elements.

Arousal of behavior, according to LST, is caused by a strain or strains in the system. Direction and persistence of behavior involve choosing acts that will reduce the strain. That is, a theory of motivation that accounts for direction and persistence of behavior must encompass the decision process. Expectancy and goal-setting theories attempt to specify the process by which a particular act, having dimensions of method, direction, intensity, and duration, is chosen and implemented. Putting these pieces together, a model may be constructed from LST concepts that combines some of the best features of the theories of need, expectancy, goal-setting, and reinforcement (Tracy 1984). Such a model is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Model of Decider-Directed Motivation.

The living systems model of decider-directed motivation offers many advantages over the traditional OB treatment of the topic. It integrates the many separate theories into a picture that covers all aspects of motivation. For management purposes it specifies the points at which motives may be influenced by external stimuli. These points of influence relate closely to path-goal theory. Although based on the principle of homeostasis, the model is dynamic in the sense that it allows for learning through positive and negative feedback loops, as well as for changes in purposes and in stimuli. It also allows for development of a model of motivational interaction between living systems (Tracy 1989: 112-115). Finally, the model is applicable to all human social systems as well as individuals. It implies, for instance, that setting goals for a corporation may have some of the same motivational effects as individual goal setting.

Decision making. Decision making, as I have implied above, is rightly treated in conjunction with motivation. It is also involved with group processes and leadership. The basic stages of the decider process and the concept of echelons within the decider subsystem (Miller 1978: 67-68) are very useful in analyzing group and organizational decision making. For instance, many problems with organizational decisions may be traced back to the fact that different stages are carried out by different echelons. Goals may be set at the top echelon. Data are then gathered by lower echelons and analyzed by middle echelons, Synthesis may then occur at the top echelon, whereupon orders are issued for implementation at lower echelons. If communication between echelons is not effective, there are many points at which the process may fall apart.

"Groupthink" is a topic normally covered in OB texts (Janis 1982). The term refers to a tendency of group members to suppress their private reservations about a group decision and go along with what they perceive to be the majority position. The result is often a poor decision based on inadequate information. This common error may be analyzed as a confusion of goals, The immediate goal of the group is to make a decision that solves a group or organizational problem, but other goals intrude. These may be group goals, such as maintenance of cohesiveness, or individual goals, such as maintenance of status within the group. The reward structure may also be involved. Are group members rewarded for good decisions, cooperativeness, or status? Although such analysis could be carried out without LST, it is facilitated by such concepts as goal-centered behavior and decider subsystems for different levels of living systems.

Leadership. The latter point deserves more discussion, because it connects to the topic of leadership. In the broadest sense, leadership is purposeful participation in the top echelon of the decider subsystem of a social system (Tracy 1983). Every living system must have its own decider subsystem. An organization is a living social system composed of other living systems. Each individual, group, department, and division within the organization has a decider subsystem making decisions, at least some of the time, on the basis of its own purposes and goals as well as those of the organization. Thus there are many leaders and levels of leadership within the organization, and many sources of conflict among them. The loyalty of each leader is divided, at the minimum, between self and the social system being served, Often, leaders serve in the top echelon of more than one social system (e.g., corporation and family, nation and party). A social system may thus be temporarily without leadership as the members of its top echelon sleep or choose to serve themselves or another system.

It is evident that LST highlights important themes concerning leadership that are usually ignored in OB. By defining leadership in terms of the top echelon of the decider, LST also links leadership to other OB topics. One link suggested above is with the topic of conflict.

Conflict. According to Miller (1978: 39), conflict is a strain that arises when a living system receives two or more incompatible commands. The commands may come from two or more systems at the same level or at different levels. Role conflict, for instance, occurs when a member of an organization receives incompatible role specifications from two superiors, or two customers, or two subordinates, or a superior and a customer, or even oneself and a superior. Conflict also occurs when a person in a committee meeting is torn between serving the goals of the department or of the organization as a whole.

Miller's definition of conflict as a strain in a living system resulting from incompatible commands serves several purposes. It connects the concept of conflict to the model of motivation discussed earlier. It clarifies the locus of conflict as being within systems rather than between them. It facilitates analysis of conflicts that arise from commands at different levels. And it emphasizes the inevitability of conflict. Conflict can be resolved or managed, but it cannot be avoided so long as we live in a world of myriad living systems, each issuing commands.

Power and influence. Managers often seek to resolve conflict through the use of power and influence. Power is another topic that is generally treated in a muddled fashion in OB literature. It is often defined in such a way that it is indistinguishable from influence, as in Dahl’s (1957: 202-3) definition, "A has power over B to the extent that [A] can get B to do something that B would not otherwise do." Such a definition confuses the concepts because it leaves no way of identifying power unless it is actually used for influence.

In living system terms power may be defined in general as possession or control of excess resources. Social power in relation to another living system may be defined as possession or control of resources that the holder regards as excess and that the other living system values positively or negatively (Tracy 1989: 124-125). This definition clearly distinguishes power from influence and tells us what to look for in order to identify power. Favorite OB models such as French and Raven's (1959) five bases of social power may then be analyzed in terms of the concepts of types of resources, excess, and positive and negative values. Authority and organizational sources of power are also clarified.

Perception and communication become important links when a living system attempts to apply power for the purpose of influence. Taking Dahl's definition as applying to influence, B must perceive that A has power and must understand what A wants done. Thus A must communicate that he/she possesses or controls certain resources, that they are excess and available for use through act X, that he/she wants B to do act Y in exchange for (or to prevent) act X, and what act Y consists of. At this point the usual OB models of effective communication come into play.

We must also consider the motivation of A and B, B's power with respect to A, and the interactive effects they have on each other. Broadening the analysis to include the effects of other systems, we may then move toward political models of coalition formation, involving the pooling of resources. Once again, the LST approach emphasizes the interlocking nature of OB concepts and models.

Boundary processes. LST possesses the power to generate new ideas concerning OB. For instance, the OB literature takes little notice of processes that hold the organization together or protect it from environmental forces. These are the processes assigned to the boundary subsystem, Granted, the field of OB does include such topics as group cohesiveness, job satisfaction, and organizational culture, but these topics are treated separately and with little recognition of their interrelatedness.

Recognition of the importance of the boundary processes allows us to incorporate these elements into a more comprehensive treatment of the ways in which groups and organizations protect themselves. Selecting new members, monitoring the environment, securing an adequate line of credit, filtering information inputs, assuring on-time delivery and quality of material inputs, assessing organizational effectiveness, providing an avenue for complaints and suggestions, forming a public relations department, and developing contingency plans for emergencies are all behaviors related to the boundary processes of an organization. Similar protective processes exist at the group and individual levels, and are the cause of various regulatory intrusions from the community and societal levels. The OB literature should recognize the pervasiveness of such behaviors, the purposes they serve, and their place among the critical processes of the living systems involved in an organization.

Summary

The field of OB has much to learn from LST. LST offers a conceptual and theoretical framework that draws together the diverse topics of OB and clarifies the ways in which they are interrelated. Through use of generic, cross-level terms and concepts we can reverse the proliferation of concepts that creates confusion and retards progress in understanding OB. LST can help us to view simultaneously the several levels of systems in and around an organization, thereby facilitating analysis of interactions between levels. It can aid us in research on processes that are difficult to access at one level, by permitting us to look at similar processes on another level. It can encourage us to look for emergents at each level. It can indicate behavioral processes that should be included within the purview of OB, so that a more complete picture may emerge. Finally, LST is a fruitful source of hypotheses for further study, hypotheses about causal relationships and cross-level interactions.

References

(1) J. S. Adams, 1963, "Toward an understanding of inequity." Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, Vol. 67, 422-436.

(2) C. P. Alderfer, 1972, Existence, Relatedness, and Growth. New York: Free Press.

(3) B. Berelson and G. A. Steiner, 1964, Human Behavior: An Inventory of Scientific Findings. New York: Harcourt.

(4) R. A. Dahl, 1957, "The concept of power." Behavioral Science, 2: 201-215.

(5) M. G. Evans, 1970, "The effects of supervisory behavior on the path-goal relationship." Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 5: 277-298.

(6) J. R. P. French and B. Raven, 1959, "The bases of social power." In D.

Cartwright (Ed.), Studies in Social Power, 150-167. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan.

(7) F. Herzberg, B. Mausner, and B. B. Snyderman, 1959, The Motivation to Work. New York: Wiley.

(8) R. J. House, 1971, "A path-goal theory of leader effectiveness." Administrative Science Quarterly, 16: 321-338.

(9) I. L. Janis, 1982, Groupthink, 2nd Ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

(10) E. A. Locke, 1968, "Toward a theory of task motivation and incentives." Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 3: 157-189.

(11) A. H. Maslow, 1943, "A theory of human motivation." Psychological Review, 50: 370-396.

(12) D. C. McClelland, 1961, The Achieving Society. Princeton: Van Nostrand,

(13) S. L. Merker, 1987, "A living systems process analysis of an urban hospital." Behavioral Science, 32: 304-314.

(14) J. G. Miller, 1978, Living Systems. New York: McGraw-Hill.

(15) J. G. Miller and J. L. Miller, 1990, "Introduction: the nature of living systems." Behavioral Science, 35: 157-163.

(16) T. R. Mitchell, 1979, "Organizational behavior." Annual Review of Psychology, 30: 243-281.

(17) H. A. Murray, 1938, Explorations in Personality. New York: Oxford.

(18) G. R. Salancik and J. Pfeffer, 1977, "An examination of need satisfaction models of job attitudes." Administrative Science Quarterly, 22: 427-456.

(19) P. Shrivastava, 1983, "A typology of organizational learning systems." Journal of Management Studies, 20: 7-28.

(20) B. F. Skinner, 1953, Science and Human Behavior. New York: Macmillan.

(21) L. Tracy, 1983, "Lack of leadership: a living systems perspective." In G. E. Lasker (Ed.), The Relation between Major World Problems and Systems Learning, Vol. 2, 569-576. Seaside, CA: Intersystems.

(22) L. Tracy, 1984, "A dynamic living-systems model of work motivation." Systems Research, 1: 191-203.

(23) L. Tracy, 1986, "Toward an improved need theory." Behavioral Science, 31: 205-218.

(24) L. Tracy, 1989, The Living Organization. New York: Praeger.

(25) V. H. Vroom, 1964, Work and Motivation. New York: McGraw-Hill.