Back • Return Home

Basic Information On Chinese Characters

[The majority of these images are taken from Wikipedia.]

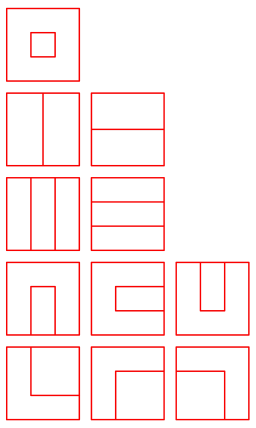

Composition

Chinese characters are composed of eight simple strokes. Here is a list of them and their corresponding names in Pīnyīn, the standard phonentic guide for Mandarin Chinese. It is okay if none of the names make sense yet. We will cover how to understand Pīnyīn elsewhere. For now, we only want to highlight how each character stroke is formed. In the following diagrams, red arrows show how they are written with a brush. Please keep in mind that the direction in which each stroke is written matters! Notice how many of them seem to taper off, or get thinner at the end of the stroke.

diǎn - a dot

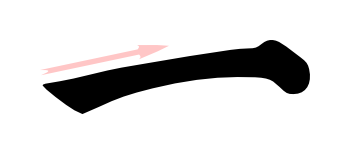

héng - a horizontal line

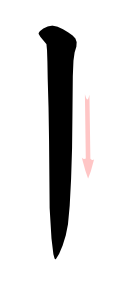

shù - a vertical line

gōu - a small hook

tí - a small flick upwards and to the right

wān - a curve to the left

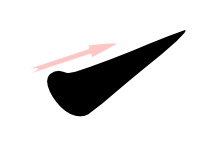

piě - a small flick downwards to the left

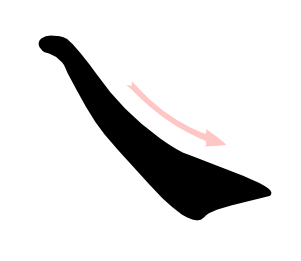

nà - a large flick downwards to the right, fanning out

When writing a character, these eight strokes can be combined in various ways within an imaginary square (shown here in red). For example:

Notice that this particular character uses all eight of the simple strokes, some of them flowing into one another without any breaks.

Every character has its own "stroke order," or sequence in which the strokes are drawn when writing that character. While this may seem arbitrary, it is important to use this stroke order! It helps one to distinguish characters that look very similar. Some characters only differ by as little as one stroke. Likewise, stroke order facilitates character recognition on smartphones and computers that allow for handwriting input.

In general, stroke order usually follows these patterns:

• Strokes move from left-to-right

• Strokes move from top-to-bottom

• Strokes move from outside-to-inside

• Strokes that close a box within the character come last

Certain collections of strokes are repeated across many different characters. Some of them are used to sort characters into groups within character dictionaries. These are called "radicals", of which there are about 200. That might seem like a lot of information to commit to memory, but we probably won't encounter many of them as some are used much more than others.

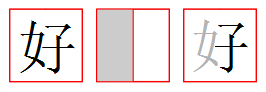

It is also important to note that what exactly is considered the "main radical" of a character is not always self-evident. However, unless one is trying to use a character dictionary printed on paper, this is of little concern. Instead, radicals are most useful for helping one to memorize characters at a glance because they often appear within specific locations within our imaginary square:

Much like how we recall "words" by their shape (i.e.: the "spelling," or order of their letters), we can use radicals in a similar manner. For example:

The character within the left-most box is made up of two distinct components (as shown by the contents of the two right-most boxes).

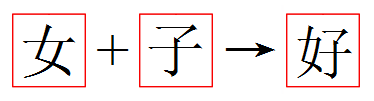

In some cases, an entire character can become a component of another. For example:

The two characters on the left combine to make the character in the right-most box. We determine whether a collection of a strokes is a character or a component of another character by the amount of space it takes up relative to our imaginary box. Notice that the two characters on the left are much smaller when used as components within the character on the right.

Sound & Meaning

Each character has at least one pronunciation (i.e.: a single syllable or vowel sound) and one general meaning associated with it.

It seems to be a common misconception that Chinese characters are like pictures (i.e.: "pictograms"). Other than a handful of them, most characters are not images of, or even symbolic representations of, the things that they are used to describe.

Further, not all characters are stand-alone "words". Some must be combined with other characters in order to make sense. To use an analogy: In English, the prefix "anti-" has a specific pronunciation and meaning, but it must be attached to something else when it is used. [In Linguistics, this is called a "bound morpheme".]

Reading

To be literate, one should understand a couple of thousand characters. However, a large amount of text can be understood with just 500 of the most common ones. This might seem overwhelming at first, but it is important to realize that most people already know thousands upon thousands of "words" and "word fragments" (i.e.: prefixes and suffixes). To return to our analogy:

• Strokes are like alphabet letters

• Characters are like syllables

• Most "words" are made up of two characters [sometimes referred to as a "bigram"]

Therefore, if we attempt to learn characters with a good awareness of stroke order and within the context of useful "words," we can maximize the speed at which we learn Mandarin Chinese.