| Tempo | Approximate BPM Range |

|---|---|

| Presto ("Fast") | |

| Allegro ("Quick and Lively") | |

| Allegretto ("Fairly Quick and Lively") | |

| Moderato ("Moderately") | |

| Andante ("Walking Pace") | |

| Adagio ("Slow and Leisurely") | |

| Largo ("Broadly") |

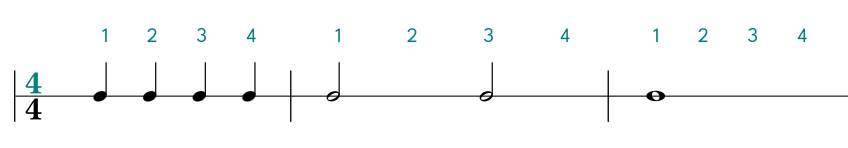

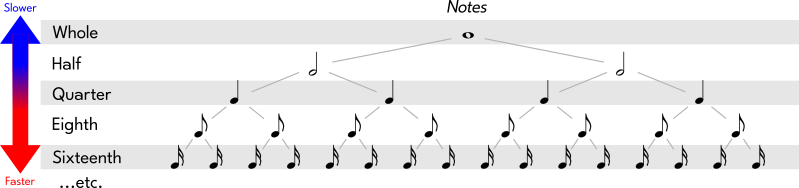

Half Note is faster than a

Half Note is faster than a  Whole Note

Whole Note

Quarter Note is faster than a

Quarter Note is faster than a  Half Note

Half Note

Eighth Note is faster than a

Eighth Note is faster than a  Quarter Note

Quarter Note

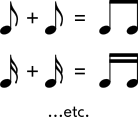

+

+  =

=

+

+  =

=

+

+  +

+  +

+  =

=

+

+  =

=

+

+  +

+  +

+  =

=

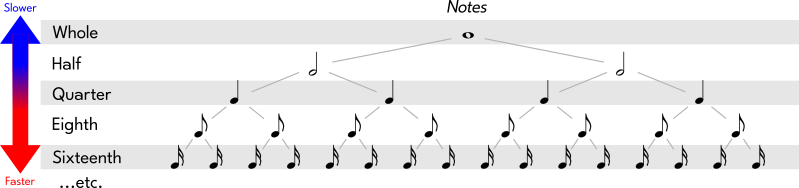

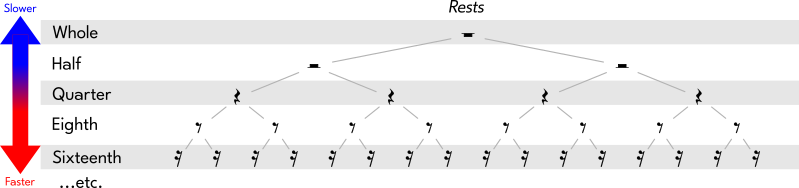

Eighth Note to a

Eighth Note to a  Sixteenth Note or an

Sixteenth Note or an  Eighth Rest to a

Eighth Rest to a  Sixteenth Rest. To get anything shorter than a Sixteenth Note or Rest, we can just add another little "flag" or "blob" to it. Therefore, a Thirty-Second Note or Rest would have three little "flags" or "blobs" on it, a Sixty-Fourth Note or Rest would have four little "flags" or "blobs" on it, and so on. While Notes and Rests can become shorter, they usually do not become this short within most pieces of music!

Sixteenth Rest. To get anything shorter than a Sixteenth Note or Rest, we can just add another little "flag" or "blob" to it. Therefore, a Thirty-Second Note or Rest would have three little "flags" or "blobs" on it, a Sixty-Fourth Note or Rest would have four little "flags" or "blobs" on it, and so on. While Notes and Rests can become shorter, they usually do not become this short within most pieces of music!

= 96

= 96