Sounds & Symbols

As Denise Eide points out in her wonderful presentation "Uncovering the Logic of English", there are approximately 44 sounds in the English langauge, but only 26 letters within the English alphabet. Therefore, some letters and combinations of letters represent multiple sounds.Word Stress

Syllables can be either "Stressed" or "Unstressed" (i.e.: one particular Syllable may be emphasized within a Word while the others are not).Lines & Meter

When it comes to poetry, Words are grouped into "Lines". The pattern of Syllables and/or Stresses within each Line is generally referred to as "Meter". There are three different ways that Meter is normally used in English:| Name | Pattern |

|---|---|

| Spondee | |

| Pyrrhic | |

| Trochee | |

| Iamb |

| Name | Pattern |

|---|---|

| Molossus | |

| Tribrach | |

| Dactyl | |

| Anapest | |

| Bacchius | |

| Antibacchius | |

| Amphibrach | |

| Amphimacer |

| Name | Number of Feet |

|---|---|

| Dimeter | |

| Trimeter | |

| Tetrameter | |

| Pentameter | |

| Hexameter | |

| Heptameter | |

| Octameter |

Stanzas & Rhyme

Lines are combined into larger groupings called Stanzas. A Stanza might have a particular name depending upon how many Lines are inside of it:| Name | Number of Lines |

|---|---|

| Couplet | |

| Triplet | |

| Quatrain | |

| Quintain | |

| Sestet | |

| Septet | |

| Octave |

Form

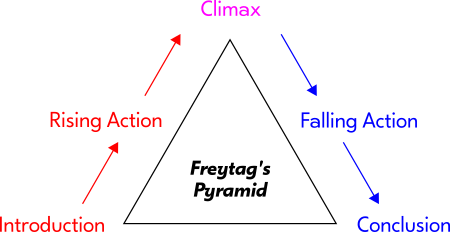

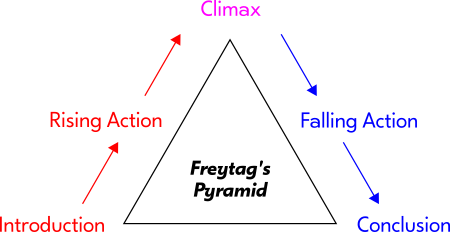

The Meter of Lines within each Stanza and the Rhyme Scheme that they follow determines the "Form" of a poem.Literary Devices

Generally, a "Literary Device" is a particular way of communicating a Meaning. To give a few examples:Poetry As Storytelling

Whether they are completely made up ("Fiction") or based in fact ("Non-Fiction"), we often tell stories of differing lengths through our poems. Whenever we write a story, there are usually several things that we focus in on, such as the motivations of and the roles fulfilled by different Characters, or the Setting (i.e.: the location and time period that they are in). If we don't know where to begin, we can ask ourselves one of the five "W" questions: "Who?", "What?", "When?", "Where?", and "Why?".

Easy Ways To Begin

There are many ways to start writing poems and/or stories. It is more a matter of finding what is most comfortable for you in that moment. Some examples: