Back • Return Home

TEN WAYS TO USE LIVING SYSTEMS THEORY

Lane Tracy

Copeland Hall, Ohio University

Athens, OH 45701

ABSTRACT

Although living systems theory (LST) is a formidable academic achievement, it has also proven to have pragmatic value. LST has been employed in a variety of ways by researchers and practitioners all over the world. To aid others in understanding the value of LST this paper codifies and highlights the many uses to which the theory has been put and suggests some additional uses.

Keywords: living systems theory, cross-level, model, icons, measurement

Living systems theory (LST) was generated by a lengthy and encyclopedic search for the critical processes and subsystems common to all forms of life, as exhibited in cells, organs, organisms, groups, organizations, communities, societies, and supranational systems (Miller, 1978). The theory purports to offer an extraction of the critical processes and structures required by all forms of life.

Although LST is necessarily very complex and analytical, like any good theory it can be very useful. In fact LST has already been employed in a variety of ways. Here is a brief list of the ways in which LST has been found to be useful:

1. Provides ready-made hypotheses to be tested.

2. Aids the generation of new hypotheses.

3. Provides a theoretical framework for cross-level disciplines.

4. Provides a set of common terms and concepts for cross-level disciplines.

5. Offers a set of standardized icons that can be used to model living systems and facilitate such processes as design and analysis.

6. Specifies what needs to be included or accounted for in developing models for various disciplines.

7. Stimulates development of new units and instruments of measurement.

8. Facilitates diagnosis and prescription of treatment for pathologies in living systems.

9. Suggests new fields of study that have not yet been tapped.

10. Suggests new approaches in fields that are faced with conflict or are at a dead end.

The purpose of this paper is to demonstrate the practical value of LST and to promote further interest in its use. The paper will examine and categorize the uses that have already been made of LST, citing sources of models for such usage. Additional ways to employ LST will also be described. The paper will conclude with suggestions for expanded employment of the theory.

Hypotheses

A primary result of Miller's (1978) cross-level analysis was the listing of 173 systems hypotheses. These hypotheses were carefully catalogued and linked to specific facets of LST, with page references indicating where a particular theoretical relationship was noted at each level of living systems.

Miller and Miller (1995) cite several tests of hypotheses generated by LST. Miller (1960, 1978) tested a hypothesis about information input overload in cells, organs, organisms, groups, and organizations. Bergström (1995) retested the hypothesis with organisms and groups. Rapoport and Horvath (1961) tested the hypothesis that a mathematical model of random nets applied both to organisms and organizations. Lewis (1981) tested a hypothesis about the effect of conflicting signals on the decider subsystems of human organisms and groups. It is likely that many more tests of cross-level hypotheses have occurred within the biological and social sciences without explicitly recognizing the fact that the test involved multiple levels, such as organs and organisms or groups and organizations.

Most of the hypotheses listed by Miller (1978) remain to be tested. Thus, one important use of LST is to supply the academic community, especially systems researchers, with hypotheses that are in need of testing.

LST also facilitates the generation of new systems hypotheses based on advances in related fields. As biological and social scientists produce new findings, additional cross-level similarities are uncovered. For example, recent findings concerning the interactions among genes and the ways in which genes turn on and off to control organic growth processes might find parallels in the interactions of various parts of the charters of social systems and the effects of those interactions on social growth. Our understanding of the process of organizational learning has developed rapidly since Miller's (1978) Living Systems was written. New hypotheses about the learning process might be generated by comparison of knowledge about the process at the levels of organisms and organizations. Newly uncovered cross-level similarities may represent previously unsuspected systems characteristics of life or elaborations on known characteristics.

Cross-level Terms, Concepts, and Frameworks

New disciplines have arisen, such as organizational behavior, memetics, conflict management, and environmental studies, which encompass research at two or more levels of life. These disciplines draw from sources that often employ different, incompatible concepts and terminology. LST provides a set of common, well-defined terms and concepts that can be used to unify a cross-level discipline. For instance, Tracy (1986) found the living systems definition of purpose to be very useful in developing a clear, cross-level concept of need. Bailey (1995) employed the LST concept of space to examine similarities and differences in the concepts of boundary, border, supporter, artifacts, territory, spacing behavior, and density effects across six levels of living systems.

LST also offers a theoretical backbone for use in such cross-level disciplines, which may otherwise be beset by conflicting conceptual structures. Thus, LST has been found to be useful as a theoretical framework in such fields as sociology (Bailey, 1990, 1994), organizational behavior (Tracy, 1989, 1994), economics (Weekes, 1995), memetics (Tracy, 1996b), conflict management (Tracy, 1995), space exploration (Harrison, 1993; Miller & Miller, 1991; O'Donnell, 1994), urban planning (Rasegård, 1991), law (O'Donnell, 1994; Tracy, 1996a), environmental studies (Frändberg, 1999), and computer software development (Ahari, 1993). It is potentially useful in other cross-level fields such as education, linguistics, political science, and sociobiology.

Icons and Modeling

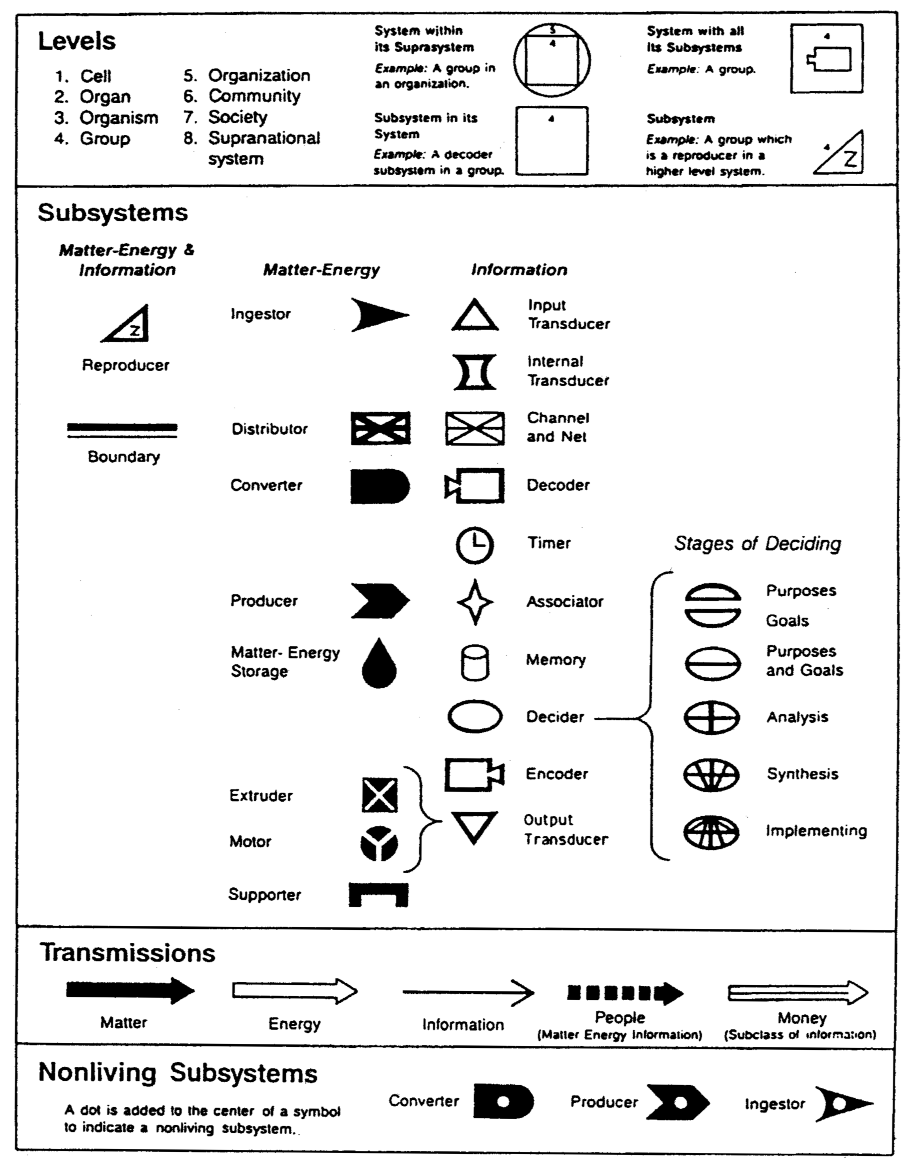

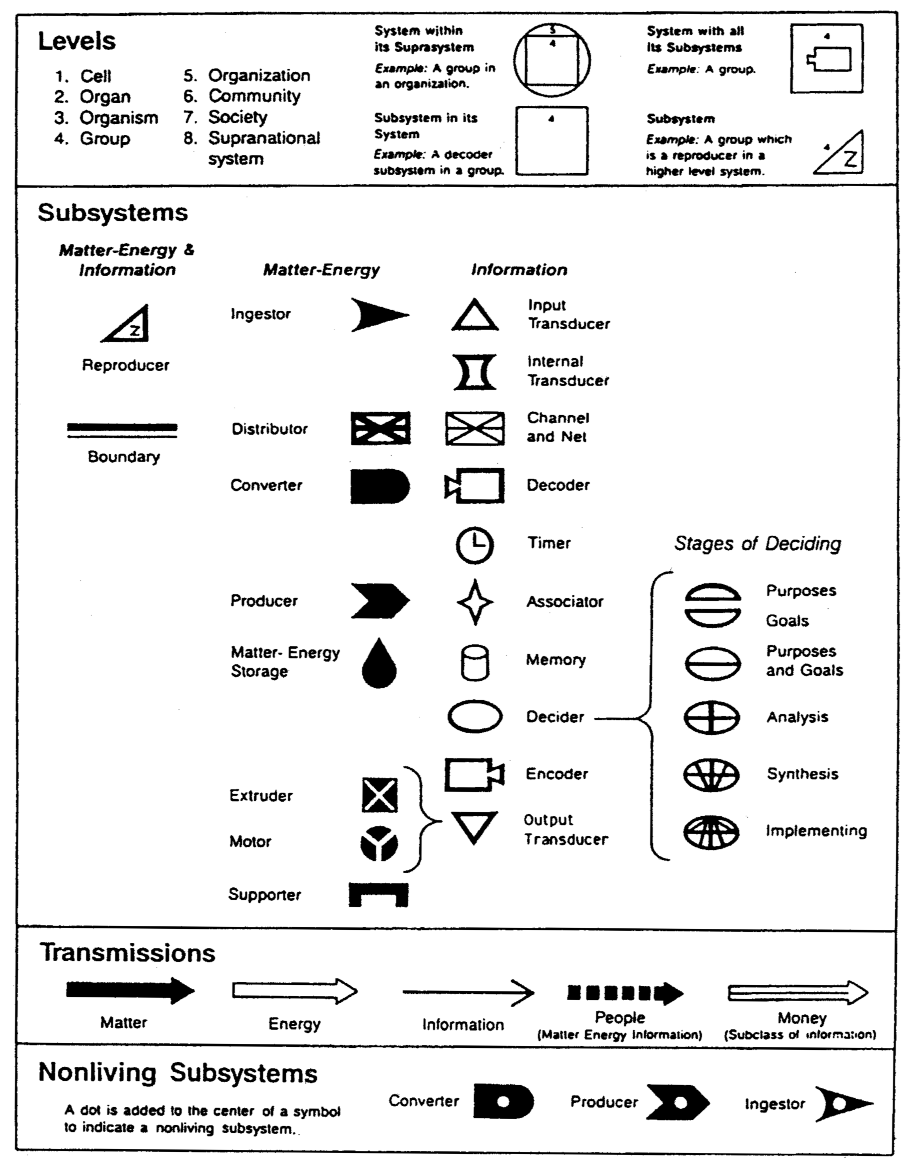

LST provides a set of standardized icons that can be used to model living systems and facilitate such processes as design and analysis. The icons represent the various critical subsystems and processes of living systems. They can be used to draw an abstract model of any living system, to examine the relationships between subsystems, to compare systems, and to prepare flowcharts. The set of icons is shown in Fig. 1.

The set of icons has been employed in a wide variety of fields. It has proven to be very useful in engineering design (Allen & Mistree, 1996; Koch et al., 1994) and software development (Holmberg, 1993), analysis of group performance in a workshop (Österlund, 1995), and analyzing interactions between subsystems at several levels (Frändberg, 1999).

LST also specifies what needs to be included or accounted for in developing models for various disciplines. For instance, LST has been used in accounting to indicate how accounts should be apportioned in order to assess a financial system properly (Swanson and Miller, 1989). Tracy (1994) used LST to generate ideas about necessary steps in developing a new business firm, Ahari (1993) employed it in the development of his POLSA model, and Rasegård (1999) applied it to planning for a municipal organization.

Figure 1. Living Systems Icons

Measurement

LST has stimulated the development of units and instruments of measurement. Simms (1999) developed and tested a set of units of measurement applicable to all levels of living systems. Swanson and Miller (1989), Louderback (1994), and Swanson, Bailey, and Miller (1997) used accounting information to measure flows and processes in social systems. Merker and Lusher (1987) and Bryant and Merker (1987) developed instruments to measure the health of organizational subsystems. These instruments were used to gather data for the purpose of diagnosing and prescribing treatment of pathologies in real organizations. Frändberg (1999) employed statistical data in a simulation program to quantify subsystems at the levels of the supranational system, society, and community.

Diagnosis and Treatment of Pathologies

LST has been employed in the diagnosis of pathologies in a variety of living systems. Several of the sources already cited are examples of this usage. Miller (1995) cites several examples of medical uses of LST at the organism and organization levels. Kolouch (1970), Kluger (1969), and Bolman (1970) employed LST in the diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric disorders. At the level of the organization Merker and Lusher (1987) analyzed the problems of an urban hospital, and Chase, Wright, and Ragade (1981) diagnosed the subsystems of the inpatient psychiatric unit of a university hospital. Other kinds of organizations that have been diagnosed with the aid of LST include a public transit system (Bryant & Merker, 1987) and a municipal organization where the analysis resulted in formulation a zero-based budgeting approach toward improvement (Rasegård, 1999). Ruscoe et al. (1985) applied LST to an analysis of effectiveness of U.S. Army battalions. At the level of the society Tracy (1996c, 1998) applied LST to the analysis of the current separation of Korean society into two parts and suggested methods to be used in the reunification process.

Prospective Uses

LST suggests new fields of study that have not yet been developed. For instance, perhaps we need a new discipline of systems evolution in which the transitions from one level of living systems to another are studied. The transition from inertness to life and from life to death could constitute a subfield. Such a field of study would contribute to the discussion of such topics as the development of artificial life and the GAIA theory concerning the living status of the earth.

There really is no distinct field of study for supranational systems, such as exists for all of the other levels of living systems. Supranational systems in the areas of politics and government (e.g., United Nations, European Union), military science (e.g., international peace-keeping operations, North Atlantic Treaty Organization), economic cooperation (e.g., North American Free Trade Agreement, European Union, International Monetary Federation, World Bank), business (global corporations), and communications (the internet) are rapidly coming to dominate the world, yet we are only beginning to study them. To understand such systems properly we need inputs from the fields of political science, economics, business, communications, military science, and many other areas. LST would provide an ideal theoretical framework for this new field of study.

It has been suggested that the field of immunology could be expanded into a cross-level discipline, since protection from invaders is important to all levels of living systems (Bosserman, 1982). For instance, using a living systems approach Walker and Thiemann (1990) analyzed the internal security system at the group level as an immune system and Tracy (1993) treated organizational defenses from the perspective of immunology. A new field of systems immunology would be able to explore further the general, cross-level characteristics of immunity subsubsystems and adjustment processes.

LST may provide insights into conflicts that exist within various disciplines. For instance, Tracy (1996a) has suggested that conflicts in the law regarding environmental protection and abortion rights might be resolved through application of LST. Indeed, the law affects living systems at many levels. It deals with the right to patent new bacteria, to donate and transplant organs, to kill deer and harvest forests, to exclude individuals from private groups, to form and dissolve families and corporations, to incorporate communities, to draft individuals in defense of the nation, and to implement treaties between nations. Eventually it must expand its dominion into space (O'Donnell, 1994). It seems obvious that application of LST would help to clarify and remove inconsistencies in the law regarding treatment of living systems at different levels.

LST works well in conjunction with other theories. For instance, Ahari (1993) and Rasegård (1999) combined LST with Breakthrough Thinking (Nadler & Hibino, 1990) to assist groups in analyzing information processing subsystems and to assess municipal processes, respectively. Österlund (1995) combined LST with informatics and various problem-solving approaches to facilitate a product development project. Bailey (1990; Swanson, Bailey, & Miller, 1997) effectively combined LST and entropy theory to develop a theory of social entropy. Járos (2000) showed how LST could be combined with Teleonics to provide an extended perspective of living systems. In this volume Tracy (2001; Tracy & Tracy, 2001) demonstrates that LST works well with soft systems methodology (SSM) to analyze pathologies in social systems and suggest treatments.

SUMMARY

Living systems theory has been used in at least ten different ways, depending on how you choose to slice them. Those applications include providing ready-made hypotheses and facilitating the generation of new hypotheses, providing a theoretical framework and a set of terms and concept for cross-level disciplines, facilitating model building through a set of standardized icons, providing a checklist of processes and structures that must be included or accounted for in developing models for various disciplines, stimulating development of new units and instruments of measurement, facilitating diagnosis and prescription of treatment for pathologies in living systems, and suggesting new fields of study and new approaches to existing fields. LST has also been applied in conjunction with several other systems approaches.

The applications of the theory have only scratched the surface, however. LST has great potential, with many areas yet to be explored. In particular it should be recognized that LST works well in conjunction with other models and theories, such a SSM, hierarchy theory, breakthrough thinking, teleonics, and informatics. Even researchers and practitioners whose primary systems orientation is toward another theory may find that LST has value for them.

REFERENCES

Ahari, P. (1993). "Purpose-oriented Living Systems Analysis," Behavioral Science, 38(4):301-305.

Allen, J., and Mistree, F. (1996). "An Overview of the Use of Living Systems Theory in Engineering Design," in Proceedings of the 40th Annual Meeting of the ISSS, (M.

Hall, ed.), ISSS, Louisville.

Bailey, K. (1990). Social Entropy Theory, State University of Albany Press, Albany.

Bailey, K. (1994). Sociology and the New Systems Theory: Toward a Theoretical Synthesis, State University of Albany Press, Albany.

Bailey, K. (1995). "The Use of Space in Living Systems Theory: Extensions and Applications," Systems Practice, 8(1):85-106.

Bergström F. (1995). "Information Input Overload, Does It Exist? Research at the Organism Level and Group Level," Behavioral Science, 40(1):56-75.

Bolman, W. (1970). "Systems Theory, Psychiatry, and School Phobia," American Journal of Psychiatry, 127:65-72.

Bosserman, R. (1982). "The Internal Security Subsystem," Behavioral Science, 27:95-103.

Bryant, D., and Merker, S. (1987). "A Living Systems Process Analysis of a Public Transit System," Behavioral Science, 32:292-303.

Chase, S., Wright, J., and Ragade, R. (1981). "The Inpatient Psychiatric Unit as a System," Behavioral Science, 26:197-205.

Frändberg, T. (1999). "Experiences of Applying General Living Systems Theory," Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 16(1):81-100.

Harrison, A. (1993). "Thinking Intelligently about Extraterrestrial Intelligence: An Application of Living System Theory," Behavioral Science, 38(3):189-217.

Holmberg, S. (1993). "Living Systems Approach: A New Paradigm for Software Engineering," Behavioral Science, 38:293-300.

Járos, G. (2000). "Living Systems Theory of James Grier Miller and Teleonics," Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 17(3):289-300.

Kluger, J. (1969). "Childhood Asthma and the Social Milieu," American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 8:353-66.

Koch, P., Peplinski, J., Allen, J., and Mistree, F. (1994). "A Method of Design Using Available Assets: Identifying a Feasible System Configuration," Behavioral Science, 39(3):229-50.

Kolouch, F. (1970). "Hypnosis in Living System Theory: A Living Systems Autopsy in a Polysurgical, Polymedical, Polypsychiatric Patient Addicted to Talwan," American Journal of Hypnosis, 13(1):22-34.

Lewis, (1981). "Conflicting Commands Versus Decision Time," Behavioral Science, 26:79-84.

Louderback, W. T. (1994). "Concrete Process Analysis (CPA) and Living Systems Process Analysis (LSPA)," Behavioral Science, 39(2):137-68.

Merker, S., and Lusher, C. (1987). "A Living Systems Process Analysis of an Urban Hospital," Behavioral Science, 32:304-14.

Miller, J. G. (1960). "Information Input Overload and Psychopathology," American Journal of Psychiatry, 116:695-704.

Miller, J. G. (1978). Living Systems, McGraw-Hill, New York.

Miller, J. G., and Miller, J. L. (1991). "Application of Living Systems Theory to Life in Space," in From Antarctica to Outer Space, (A. Harrison, Y. Clearwater, and C. McKay, eds.), Springer Verlag, New York.

Miller, J. G., and Miller, J. L. (1995). "Applications of Living Systems Theory," Systems Practice, 8(1):19-46.

Nadler, G., and Hibino, S. (1990). Breakthrough Thinking, Prima Publishing, Rocklin, CA.

O'Donnell, D. (1994). "Founding a Space Nation Utilizing Living Systems Theory," Behavioral Science, 39(2):93:116.

Österlund, J. (1995). "Individual Competence and Group Behavior within a Living System," Behavioral Science, 40(1):15-21.

Rapoport, A., and Horvath, W. (1961). "A Study of a Large Sociogram," Behavioral Science, 6:279-91.

Rasegård, S. (1991). "A Comparative Study of Beer's and Miller's Systems Designs as Tools when Analyzing the Structure of a Municipal Organization," Behavioral Science, 36:

Rasegård, S. (1999). "Some Aspects of the Usefulness of Living Systems Theory in a Municipal Organization," Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 16(1):57-80.

Ruscoe, G., Fell, R., Hunt, K., Merker, S., Peter, L., Cary, J., Miller, J. G., Loo, B., Reed, R., and Sturm, M. (1985). "The Application of Living Systems Theory to 41 U. S. Army Battalions," Behavioral Science, 30:7-50.

Simms, J. (1999). Principles of Quantitative Living Systems Science, Kluwer Academic/Plenum, New York

Swanson, G. A., Bailey, K., and Miller, J. G. (1997). "Entropy, Social Entropy and Money: A Living Systems Theory Perspective," Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 14(1):45-65.

Swanson, G. A., and Miller, J. G. (1989). Measurement and Interpretation in Accounting: A Living Systems Approach, Quorum Books, New York.

Tracy, A., and Tracy, L. (2001). "Dysfunctional Social Systems: The Case of Aid to Refugees in Africa," Proceedings of the 45th Meeting of the ISSS.

Tracy, L. (1986). "Toward an Improved Need Theory: In Response to Legitimate Criticism," Behavioral Science, 31(3):205-18.

Tracy, L. (1989). The Living Organization: Systems of Behavior, Praeger, New York.

Tracy, L. (1993). "Immunity and Error Correction: System Design for Organizational Defense," Systems Practice, 6(3):259-74.

Tracy, L. (1994). Leading the Living Organization, Quorum Books, Westport.

Tracy, L. (1995). "Negotiation: An Emergent Process of Living Systems," Behavioral Science, 40(1):41-55.

Tracy, L. (1996a). "Living Systems and the Law," in Proceedings of the 40th Annual Meeting of the ISSS, (M. Hall, ed.), ISSS, Louisville.

Tracy, L. (1996b). "Genes, Memes, Templates, and Replicators," Behavioral Science, 41(3):205-14.

Tracy, L. (1996c). "Negotiation for Unification Process between North and South in Korea: Living Systems Approach," in Complex Systems Model of South-North Korean Integration, (Y. P. Rhee, ed.), Seoul National University Press, Seoul.

Tracy, L. (1998). "Birth, Death, and Dormancy: Implications of Living Systems Theory for a United Korean Society," in Complexity of Korean Unification Process: Systems Approach, (Y. P. Rhee, ed.), Seoul National University Press, Seoul.

Tracy, L. (2001). "Dysfunctional Social Systems: The Case of Health Care Insurance in the U. S." Proceedings of the 45th Meeting of the ISSS.

Walker, J., and Thiemann, F. (1990). "The Relationship of the Internal Security System to Group Level Organization in Miller’s Living Systems Theory," Behavioral Science, 35:147-53.

Weekes, W. (1995). "Living Systems Analysis and Neoclassical Economics: Towards an New Economic Paradigm," Systems Practice, 8(1):107-15.